1. Introduction

Chemical silicate weathering (CSW) denotes the low-temperature transformation of silicate materials (minerals and amorphous substances) by coupled dissolution-precipitation reactions (Hellmann et al., 2012; Ruiz-Agudo et al., 2016). CSW is ubiquitous and quantitatively redistributes elements among Earth’s solid and fluid reservoirs, affecting natural acid-base equilibria, global biogeochemistry, and Earth surface conditions (E. K. Berner & Berner, 2012; Ébelmen, 1845; Kump et al., 2000; Urey, 1952). Enhancing CSW in terrestrial and marine environments is discussed as a viable option aiding ocean alkalinization and societal decarbonization (CO2 removal from the atmosphere) (Hartmann et al., 2013; Longman et al., 2020; Matter et al., 2016; Meysman & Montserrat, 2017). While natural CSW fluxes are traditionally ascribed to either continental or oceanic crust weathering (R. A. Berner et al., 1983; Caldeira, 1995; Hartmann et al., 2014; Hilton & West, 2020), CSW in marine sediments is increasingly recognized as a common part of shallow diagenetic reaction networks, exerting biogeochemical fluxes that potentially rival crustal weathering (R. C. Aller & Wehrmann, 2025; Isson et al., 2020; Jeandel & Oelkers, 2015; Mackenzie & Garrels, 1965; Michalopoulos & Aller, 1995; Rahman et al., 2017; Rude & Aller, 1989; Sillén, 1967; Wallmann et al., 2008, 2023). However, the corresponding biogeochemical fluxes, particularly of alkalinity and carbon, and the underlying reaction patterns are poorly constrained (Trapp-Müller et al., in press; Wallmann et al., 2023).

A substantial body of research has concentrated on disentangling diagenetic weathering dynamics and constraining the resulting biogeochemical fluxes and their governing factors, largely using chemical analyses of sediments and porewaters and/or sediment mineralogy and petrography (Ehlert et al., 2016; Maher et al., 2006; Meister et al., 2022; Michalopoulos & Aller, 2004; Rahman & Trower, 2023; Torres et al., 2020, 2022; Wallmann et al., 2023).

Measurements of sediment composition and porewater chemistry in combination with reaction-transport models are then used to quantify reaction rates and related elemental fluxes (Du et al., 2022; Ehlert et al., 2016; Maher et al., 2006; Wallmann et al., 2008). However, interpretations and comparison of model results can be complicated by analytical artifacts, such as temperature and pressure effects on solubility (Cetiner et al., 2023; De Lange et al., 1992; Siever et al., 1965) or physical disturbance of the sediment-water interface upon sampling. Additional problems may arise from missing observational constraints and differences in the kinetic formulations applied. For example, dissolution and precipitation rates or operationally defined net weathering rates are commonly quantified by numerical fitting of parameters in study-specific rate laws (Meister et al., 2022; Wallmann et al., 2008). Although informative, kinetic constants obtained in this way often lack a mechanistic basis, are scarce, and cannot be compared directly, impeding generalizations and predictions (Hellevang et al., 2013; Krissansen-Totton & Catling, 2020; Tosca et al., 2016; Tosca & Masterson, 2014).

Si-isotopic data of marine sediments and porewaters in particular have elucidated the relative roles and contributions of lithogenic, biogenic and authigenic silicates to benthic Si fluxes (Closset et al., 2022; Ehlert et al., 2016; Geilert et al., 2023; Luo et al., 2022; Rahman et al., 2017; Ward et al., 2022). Moreover, Sr isotope systematics in active margin sediments have demonstrated a tight coupling between diagenetic CSW and carbonate authigenesis (Hong et al., 2020; Torres et al., 2020). In addition, isotopic signatures of Mg and K in various marine sediments attest to widespread silicate authigenesis (Chanda et al., 2023; Higgins & Schrag, 2015; Li et al., 2022; Santiago Ramos et al., 2018). However, a full assessment of net reaction balances and environmental influences, information required to generalize findings from such isotopic studies and to quantitatively assess biogeochemical impacts, is generally lacking (Trapp-Müller et al., in press; Wallmann et al., 2023). For example, the relative contributions of cation-depleted vs cation-enriched Al-sources to clay authigenesis and ambient solution chemistry may determine whether the reactions net produce alkalinity and sequester CO2 (‘forward weathering’) or produce acidity and release CO2 (‘reverse weathering’), but Al dynamics are rarely considered in much detail (Trapp-Müller et al., in press; Wallmann et al., 2023). Although qualitative, observation-based frameworks for occurrences of marine authigenic minerals exist and have partly been linked to terrestrial and marine reactant supplies (Aplin & Taylor, 2012; R. A. Berner, 1981; Kastner, 1999; Müller, 1967), these frameworks have not yet been tested against thermodynamic and kinetic constraints, nor linked to concepts of diagenetic weathering fluxes, depositional environments and Earth’s weathering feedback (R. C. Aller & Wehrmann, 2025; Mackenzie & Garrels, 1966; Torres et al., 2020; Trapp-Müller et al., in press; Wallmann et al., 2023).

Episodically reworked, deltaic ‘mobile’ muds are a major sedimentary facies along the river-dominated ocean margins (Bao et al., 2019; Kuehl et al., 1986, 2019; Liu et al., 2018; McKee et al., 2004). A dominant fraction of the terrigenous sediments reaching the ocean transits through them for multiple years, entraining large amounts of reactive marine-biogenic particles and exchanging materials with ocean and shoreline before eventually reaching longer term depocenters (Anthony et al., 2010; Kuehl et al., 2019; Song et al., 2022) (fig. 1). Low latitude mobile muds represent efficient batch reactors, organic carbon ‘incinerators’, and global hotspots of K, Mg and F consumption, biogenic Si sequestration and likely reverse weathering, (R. C. Aller et al., 2008; R. C. Aller & Blair, 2006; Bao et al., 2018; Ku & Walter, 2003; Michalopoulos & Aller, 1995, 2004; Rahman et al., 2017; Rude & Aller, 1989, 1994; B. Zhao et al., 2017). These deltaic systems often remove substantial fractions of the corresponding riverine solute fluxes and biogenic particle inputs. For example, diagenetic silicate weathering in the Amazon-Guianas mobile muds alone may remove ~10 % of the global riverine K supply (R. C. Aller, 2004; Michalopoulos & Spiegel, 2021), ~2% of the global riverine F- supply (Rude & Aller, 1994), up to 67 % of the Mg (Rude & Aller, 1989) , and ~50 % of the dissolved Si delivered by the Amazon river (Rahman et al., 2016). Due to seasonal reworking, the corresponding reaction-transport dynamics can deviate substantially from traditional (‘plug-flow’) diagenetic models, which assume steady and undisturbed sediment accummulation (R. C. Aller, 2004; R. A. Berner, 1980).

To constrain the main factors governing net reaction outcomes in deltaic mobile mud belts, we explored the evolution of diagenetic conditions within mobile muds and the coupled responses of silicate weathering and mineral authigenesis. First, we reviewed dominant features of marine diagenetic weathering, and then constructed a batch reaction model suitable for mobile mud diagenesis over the characteristic timescales of episodic deposition. The model combines equilibrium aqueous chemistry with kinetic concepts from sediment biogeochemistry (R. A. Berner, 1980; Soetaert et al., 1996) and mineral sciences (Aagaard & Helgeson, 1982; Hellevang et al., 2013; Tosca et al., 2016). We implemented two approaches to silicate precipitation: (I) an explicit formulation of nucleation-growth mechanisms (‘PHA’, based on Hellevang et al. (2013) and Pham et al. (2011)) and (II) a phenomenological pH-dependent, Si-limited batch rate law (‘TIP’, based on Isson and Planavsky (2018) and Tosca et al. (2016)). Both model setups were scaled to resemble quantitative and qualitative observations from mobile muds of the Amazon delta topset. Subsequent model experiments, linear global sensitivity analyses, and comparison to observations from a wide range of sedimentary environments were then used to develop a general, explanatory framework of diagenetic silicate weathering products and fluxes with respect to sediment sources and depositional environments.

2. Weathering reaction balances and marine environments

2.1. Weathering reaction balances: ‘forward’ and ‘reverse’ components

The weathering process represents a dynamic continuum of intricately coupled dissolution and precipitation reactions releasing and/or consuming solutes (Hellmann et al., 2012; Niedermeier et al., 2009; O’Neil & Taylor, 1967):

Dissolution+Precipitation=Solute Flux

where Dissolution and Precipitation are each a series of reactions that are locally coupled at the dissolution front (Hellmann et al., 2012; Ruiz-Agudo et al., 2012, 2016) and may decouple in space and time, as suggested by Frings et al. (2014) and Wallmann et al. (2008). Congruent dissolution or homogeneous nucleation from an initially supersaturated solution are possible too. Dissolution exerts a flux to solution (> 0), while Precipitation consumes solutes (< 0) so that the resulting net Solute Flux can be either positive or negative. To maintain charge balance, the hypothetical ‘net charge’ of the direct Solute Flux after accounting for speciation is compensated by re-equilibration of local acid-base systems, primarily CO2-HCO3--CO32- transformations in Earth surface environments (Middelburg et al., 2020). Thus, the carbon cycle impact of weathering reactions is best quantified through changes in alkalinity, similar to other biogeochemical processes (Middelburg et al., 2020; Soetaert et al., 2007; Trapp-Müller et al., in press).

‘Forward’ and ‘reverse’ weathering can be described as two endmembers of a reaction continuum, transforming CO2 to HCO3- (increasing alkalinity) or transforming HCO3- into CO2 (reducing alkalinity), respectively (Isson et al., 2020; Mackenzie & Garrels, 1966b; Trapp-Müller et al., in press). Net forward silicate weathering typically transforms cation-rich silicates (e.g., feldspar or mafic minerals) into cation-depleted, Si-Al-enriched secondary phases (e.g., smectite, kaolinite or opal), e.g.:

Cation−rich silicate+CO2+H2O→Cation−poor silicate+cations(Na+,K+,Ca2+,Mg2+,Mn2+,Fe2+)+Si(OH)4+(Fe(OH)3(s)+Al(OH)3(s))+HCO−3

Such a weathering stoichiometry is characteristic for dilute, acidic to circum-neutral continental freshwaters and forms the basis of the negative weathering feedback on atmospheric CO2 and hydro-climate that stabilizes the carbon cycle over geological timescales (R. A. Berner, 1991; Brantley et al., 2023; Ruiz-Agudo et al., 2016). Reaction dynamics are further moderated by the physicochemical evolution of the altering grain’s reactive interface (Hellmann et al., 2012; Luttge et al., 2019; Müller et al., 2022), and by tectonic-geomorphological boundary conditions (Stallard, 1985; von Blanckenburg, 2005; West et al., 2005).

While forward weathering in anoxic marine sediments has been observed (Torres et al., 2020; Wallmann et al., 2008), net alkalinity-neutral and reverse weathering balances become feasible in oceanic environments (Aloisi et al., 2004; Ku & Walter, 2003; Mackenzie & Garrels, 1965; Michalopoulos & Aller, 1995; Wallmann et al., 2023). Generally, the oceans high ionic strength promotes dissolution and weathering rates (Gruber et al., 2019; Rimstidt et al., 2016; Wallmann et al., 2023), while the higher pH and cation availability (compared to freshwaters) should also promote the precipitation of cation-rich secondary phases. In terrigenous marine muds, the dissolved and particulate products of (terrestrial) forward weathering (eq 2) and biogenic silica recombine, eventually reversing some of the large-scale effects of forward weathering (Ku & Walter, 2003; Mackenzie & Garrels, 1965, 1966; Michalopoulos & Aller, 1995), e.g.:

Cation−poor silicate+cations(Na+,K+,Ca2+,Mg2+,Mn2+,Fe2+)+Si(OH)4+(Fe(OH)3(s)+Al(OH)3(s))+HCO−3→Cation−rich silicate+CO2+H2O

A variety (or sequence) of secondary minerals or amorphous substances (non-crystalline and by definition not a mineral) has been observed in marine sediments, including opal (Riech & von Rad, 1979; van Bennekom et al., 1989), ‘palagonites’ (amorphous replacement products of volcanic glasses) (Stroncik & Schmincke, 2002), clays (e.g., smectites, mica-group clays, chlorites and serpentines) (Aplin & Taylor, 2012; Müller, 1967), zeolites (Hay, 1966; Kastner, 1979; Stroncik & Schmincke, 2001) and even K-feldspar (Milliken, 2003; Müller, 1967), implying substantial variation in net reaction balances. Moreover, the precipitation kinetics may be moderated by metastable intermediates (Steefel & Van Cappellen, 1990; Tosca et al., 2016), which may or may not change in composition during recrystallization and ripening. The net weathering flux is the result of the balance between dissolution and precipitation, whose interplay depends on transport-phenomena and ambient reactions, such as organic matter degradation in marine sediments (Aplin & Taylor, 2012; Baldermann et al., 2013; Burst, 1958; Michalopoulos & Aller, 1995; Wallmann et al., 2008). Thus, weathering reaction balances and net fluxes in marine sediments vary laterally and vertically with reactant mixture (sediment sources) and physical and biogeochemical boundary conditions (sediment dynamics, diagenesis) (R. C. Aller & Wehrmann, 2025).

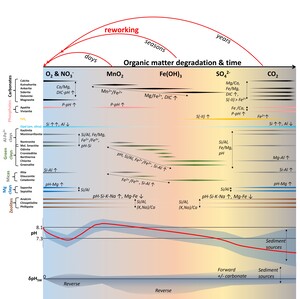

2.2. Marine weathering environments

In marine sediments, transitions between (carbonate-forming) forward weathering, near alkalinity-neutral and reverse diagenetic weathering occur in space and/or time as either reactant mixes (sediment provenance, compound depletion or involvement of oceanic crust) (Aplin & Taylor, 2012; Milliken, 2003; Torres et al., 2022) or biogeochemical conditions change (Aplin & Taylor, 2012; Scholz et al., 2013; Wallmann et al., 2008).

Generally, the forward weathering component is promoted by the presence of cation-rich reactants, such as feldspar, tephra or mafic minerals. Indeed, immersion of these materials in (oxic) standard seawater commonly results in substantial element release and, sometimes, alkalinity generation (Gruber et al., 2019; Jeandel & Oelkers, 2015; Jones et al., 2012; Montserrat et al., 2017). The reverse weathering component appears to strengthen with increasing degree of previous terrestrial alteration and porewater Si concentrations (Delerce et al., 2023; Mackenzie & Garrels, 1965; Mackin, 1986). Weathering of common clays, i.e., terrestrial weathering products, in oxygenated standard seawater and analogues often results in acidification and cation-uptake (Caillère & Hénin, 1949; Mackenzie & Garrels, 1965; Swindale & Fan, 1967). A portion of terrestrial weathering products is composed of amorphous Si-Al(-Fe)(oxy-)hydroxide nanoparticles (C. V. Putnis & Ruiz-Agudo, 2021) that are hard-to-detect but appear to cover large fractions of common clay surfaces (Tsukimura et al., 2021). The supply of these weathering products varies with climate and runoff (Müller et al., 2021; Poulton & Raiswell, 2002), eventually driving latitudinal diagenetic weathering patterns along the continental margins (Aplin & Taylor, 2012; Ku & Walter, 2003; Odin, 1990).

Besides reactant distributions, the net fluxes and acid-base impacts are moderated by variation in precipitation, strengthening the reverse component under seawater compared to freshwater conditions (Fuhr et al., 2022; Sillén, 1967; Trapp-Müller et al., in press; Wallmann et al., 2023). Besides internal reaction-transport feedbacks that can self-accelerate or inhibit the weathering process (Du et al., 2022; Hellmann et al., 2012; Müller et al., 2022), the balance of dissolution and precipitation and nature of precipitate are sensitive to ambient physical and biogeochemical conditions (Aplin & Taylor, 2012; R. A. Berner, 1981; Hellmann et al., 2012; Wallmann et al., 2008). In marine sediments, ambient biogeochemistry is largely governed by the effects of organic matter degradation, availability of dissolved and particulate electron acceptors (R. A. Berner, 1981; Froelich et al., 1979; Soetaert et al., 1996) and degree of physical or biological disturbance (R. C. Aller, 1994; R. C. Aller & Wehrmann, 2025; Bao et al., 2018).

Dissimilatory Mn and Fe reduction (DMR and DIR, respectively) in muddy and organic-bearing ocean margin sediments, promote manganous and ferruginous conditions that facilitate the formation of cation-rich ‘green clays’ (Aplin & Taylor, 2012; Michalopoulos & Aller, 2004; Odin, 1990). Green clay stabilities depend critically on the local redox potential, particularly Fe2+/Fe3+ (Burst, 1958; Cloud, 1955) and are thus often associated with microenvironments (Baldermann et al., 2013; Odin & Morton, 1988), fluctuating redox conditions (R. A. Berner, 1981; Cloud, 1955; Michalopoulos & Aller, 2004), and partially ventilated, iron-rich surface sediments (Giresse et al., 2021; Giresse, 2022; K. Wang et al., 2015; B. Zhao et al., 2017). Moreover, glauconite forms in some deep-sea environments that receive sufficient organic matter to deplete O2 and NO3-, but not all metal (oxy-)hydroxides (R. A. Berner, 1981; Cloud, 1955). In tropical deltaic muds, metal (oxy-)hydroxides are often supplied by rivers in excess and episodic reworking, re-oxidation, and mixing with marine-biogenic matter (figs. 1, 2) cause ferruginous conditions to dominate the depositional periods (R. C. Aller, 1998, 2004).

Protracted reworking and material exchange with adjacent shelf environments enhance both, suboxic organic matter degradation and silicate weathering rates, driving globally significant biogeochemical fluxes (R. C. Aller et al., 2008; R. C. Aller & Blair, 2006; Bao et al., 2018; Michalopoulos & Aller, 2004; Rahman et al., 2016). Because green clays are comparably cation-rich and often form from cation-depleted lateritic sediments and biogenic silica (bSi), these reaction balances are thought to host significant reverse weathering (Ku & Walter, 2003; Michalopoulos & Aller, 1995). However, these presumably reverse weathering balances are offset towards neutrality by coupled DIR and the common involvement of feldspar as a reactant (Michalopoulos & Aller, 1995; Wallmann et al., 2023).

Many shallow continental margin sediments off the highly energetic and frequently disturbed regions stabilize for years or decades rather than seasons, so that most iron is trapped in authigenic minerals, and sulfidic or methanic conditions can develop (R. C. Aller, 2004; R. A. Berner, 1980). Both, detrital and authigenic clays, eventually (re-)dissolve under anoxic conditions, possibly producing alkalinity and authigenic carbonate (Meister et al., 2022; Zhang & Tutolo, 2021). Silicate dissolution could represent a relevant source of iron to FeSx, net increasing alkalinity while sequestering reduced sulfur and iron (Boudreau & Canfield, 1988). In methanic Black Sea sediments, plagioclase-to-smectite weathering releases Ca and Sr, but consumes Na, K, Li and B, resulting in an approximately alkalinity-neutral weathering flux (Aloisi et al., 2004). If local Ca release and alkalinity generation become substantial, inorganic calcite precipitation may be induced, recycling these components in addition to carbon storage (Caldeira, 1995; Torres et al., 2020). Such in situ carbonation represents a solid sink of local respiratory rather than atmospheric CO2 (Torres et al., 2020; Wallmann et al., 2008, 2023), i.e., an organic-inorganic carbon sink switch, similar to organic phosphorous retention authigenic phosphate minerals (Ruttenberg, 1992). Forward and carbonate-forming marine silicate weathering seem to be very common in slope sediments, particularly in those influenced by volcanic activity (Hong et al., 2020; Middelburg, 1990; Torres et al., 2020; Wallmann et al., 2008, 2023). The development of a predictive reaction-solute speciation model that incorporates organic matter diagenesis, mineral authigenesis and silicate weathering allows us to disentangle the roles of individual reactants and biogeochemical conditions in shaping weathering balances, and to test these relationships based on comparison of thermodynamic and kinetic data with field observations.

3. Methods

Weathering reaction balances reflect reactant supply, diagenetic redox zonation, and transport conditions associated with specific depositional environments. Here we emphasize reaction patterns within fine-grained sediment mixed layers that are typical of the topset facies (delta front, delta shelf facies) within many energetic subaqueous deltas and estuarine turbidity maximum zones. In the delta topset, mud layers of ~0.1–1 m thickness are episodically mobilized, exposed to oxygenated water, and re-deposited (R. C. Aller et al., 2008; Kuehl et al., 1986, 2019; McKee et al., 2004). The timescales of such deltaic reworking typically vary from tidal (daily) to interannual, affecting smaller and larger sediment volumes, respectively (Anthony et al., 2010; Kineke et al., 1996). Here we consider conditions affecting relatively thick layers of sediment (> 0.1 m) that stabilize for ~3–9 months between episodes of flood-induced reworking in the Amazon delta (Mackin et al., 1988).

In this context, we developed a time-dependent chemical batch model in which equilibrium aqueous solution chemistry and (non-equilibrium) sediment composition evolve dynamically in response to the kinetics of organic matter degradation and a set of inorganic dissolution and precipitation reactions, including silicates, carbonates, (oxy-)hydroxides, sulfides and phosphates (table 1), and exchange of adsorbed Na+, K+, Mg2+, and Ca2+ for NH4+, Mn2+ and Fe2+ on bulk sediment surfaces. We define the model domain as the center of a thick and freshly deposited mud layer, where macrofauna are absent and the sediment can be considered a closed, unsteady batch reactor over the characteristic timescale of episodic deposition (R. C. Aller, 2004). Thus, transport-phenomena are not included. The model requires initial sediment composition, solution chemistry (assumed to be standard seawater at salinity 35 (Brown et al., 1995) with biologically depleted N(V) and P(V) concentrations, table S1) and porosity (constant, 0.8) as inputs. It generates reaction rates, chemical fluxes, evolving solution chemistry and particle composition.

Because aqueous speciation is typically much faster than particle-water interactions, we model equilibrium aqueous speciation, including pH and alkalinity, and mineral saturation indices, stepwise using the PHREEQC-COM module (Parkhurst & Appelo, 2013). This module allows scripting model scenarios, mass balances, kinetics, and sensitivity analyses in MATLAB R2023b (The MathWorks, Inc., 2023) using parallel computing for computational efficiency. Activity coefficients are determined at each timestep through specific ion interaction theory (sit.dat) (Giffaut et al., 2014) to account for the high ionic strength of seawater. To complete the thermodynamic database for our purposes, pyroxene, olivine and basaltic glass were added from literature (Aradóttir, Sonnenthal, Björnsson, et al., 2012) and chrysotile from phreeqc.dat (Supplementary Data S1). For plagioclase and chlorite, reaction enthalpy and solubility constants were estimated by linear interpolation between Ca-Na and Mg-Fe endmembers, respectively, in sit.dat. A K-Si-rich Fe2+-mica (10 Å basal spacing) forms in Amazon sediments (Michalopoulos & Aller, 1995, 2004), but we lack thermodynamic data for inclusion. Celadonite, a potential substitute, is rarely observed in nature, is significantly more cation-rich and remains largely undersaturated under the observed bulk porewater conditions, so that it cannot be used as an adequate alternative. Thus, we also included the ‘Amazon clay’ with the measured composition (Michalopoulos & Aller, 1995) and the thermodynamic data of Fe2+-rich illite from (sit.dat). Reaction rates and solute fluxes of OM degradation and inorganic dissolution-precipitation are described by a variety of approaches and the resulting differential equations are ‘stiff’ (e.g., Boudreau, 1997; Hellevang et al., 2013) and solved at discrete timesteps (0.056 days ~80 min), referenced to the composition at the previous timestep. The timestep was chosen to avoid negative concentration errors and facilitate computational efficiency. Stepwise amounts of solid phases and dissolved species (M = mol per liter solution) are then added or removed to/from the previous sediment (in MATLAB) and solution (via REACTION keyword in PHREEQC)) after a fraction of the NH4+, Mn2+ and Fe2+ fluxes are exchanged for Na+, K+, Mg2+, and Ca2+ at surface sites. Thus, the mass balances for total molar concentration (M) of dissolved element (and each oxidation state separately for redox-sensitive elements) at each timestep (dt) are given by:

d[C]dt=P∑iRiνC,idt−Fsorp

P is the number of solid phases i considered in the model, t is the time (yr), Ri is the reaction rate (M/yr, i.e., normalized to one liter of solution (porewater) for all kinetic reactions) with respect to the solid i (dissolution/degradation: R < 0, precipitation: R > 0) and νC,i the stoichiometric coefficient (molar fraction) of element C in solid i. The sorption fluxes (Fsorp) of NH4+, Mn2+ and Fe2+ scale directly with the corresponding particle-water fluxes by a constant adsorbed fraction of C (Kχ,C = Cχq/C, where χ is an adsorption site and q the cation charge) that is observationally constrained to ~0.5 for NH4+ (calculated from 1.3 µmol/g/M (Mackin & Aller, 1984a) assuming a porosity of 0.8 and sediment density of 2.7 g/cm3) and calculated for Mn2+ (0.55) and Fe2+ (0.59) by rearranging mass action laws, reflecting relative thermodynamic preferences:

Cχ2C=(KNH+4)2KC(NH+4NH4χ)2

The thermodynamic constants (Kχ,C) and reaction stoichiometries are taken from phreeqc.dat. Our calculated values for Kχ,Mn are somewhat higher than available field-based estimates from Skagerrak sediments (~0.1–0.01 µmol/g/M) (Canfield et al., 1993). These sorption fluxes are charge balanced by Na+, K+, Mg2+, and Ca2+ fluxes in equivalent fractions corresponding to seawater-equilibrated clays (Sayles & Mangelsdorf, 1977). This simplified, phenomenological treatment assumes unbounded availability of sorption sites and exchangeable Ca2+ and Na+, but does not require numerical solutions, improving model efficiency. Sorption is also implicit in the choice of exchangeable cation in the (charge-balanced) composition of smectites (montmorillonite and mixed-layer smectite). Moreover, Fe(OH)3 includes small amounts of Si and Al (Mackin & Aller, 1984c) (table 1). For particles, mass balances are given by:

dXidt=Ri+P(øi)∑jRjνi,jdt

Xi (mol/L) is the molar concentration of i and j is another solid phase that directly affects i during its reaction, which applies only to MnO2 and Fe(OH)3 through anaerobic respiration and to Al(OH)3 through clays. Because porosity is fixed, the total volume of sediment and solution are both conserved, while solid composition is updated at each timestep by considering individual molar mass changes and normalizing to the given total solid phase volume. Mass changes of solid phases are rather small in this study (< 1 wt%) so that these simplifications (fixed porosity) do not significantly affect our results and conclusions. The carbonate assemblage (calcite, kutnahorite, ankerite, siderite, table 1) was chosen according to observations from the Amazon delta and elsewhere (R. C. Aller & Wehrmann, 2025; Mucci, 2004; Z. Zhu et al., 2002). The clay assemblage was limited to a minimum set that resembles the most common authigenic clays found at continental margins: kaolinite, smectites (dioctahedral montmorillonite and Fe-rich mixed-layer smectite, micas (illite, glauconite, Amazon clay), chlorite and serpentine (chrysotile) (Aplin & Taylor, 2012; Baldermann et al., 2013; Burdige, 2006; Giresse, 2022; Michalopoulos & Aller, 2004; Müller, 1967; Rude & Aller, 1989; Worden & Burley, 2003). We did not include generally undersaturated authigenic clays (e.g., berthierine or cronstedtite) and extremely supersaturated Mg-clays, such as saponite and sudoite (> 103–105 times in the initial Si-poor solution, calculation not shown) that are rather rarely observed in shelf sediments (Aplin & Taylor, 2012; Müller, 1967; Odin, 1990). Note that possible effects of sudoite- and saponite-like (Mg-rich) clays on reaction balances are largely covered by chlorite and chrysotile. The two most common diagenetic phosphates, apatite and vivianite were included (Egger, Jilbert, et al., 2015; R. A. Jahnke et al., 1983; M. Zhao et al., 2020). Solid solutions are not considered here for simplicity, although they are likely (Mackin, 1986; Middelburg et al., 1987). All kinetic rate laws used are detailed in sections 3.1–3.4, section 3.5 gives an overview over the model scenarios, and section 3.6 describes the sensitivity analysis. Parameter values, references and assumed properties of individual solid phases (density, specific surface area, molar mass, stoichiometry, and reference names in our modified database) are provided in tables 1–2 and S1–S2, and Supplementary Data S1. Model codes are available from the corresponding author upon request.

3.1. Organic matter degradation

Microbial organic matter oxidation and fermentation were described using a simple 2-G approach (two reactivity pools), differentiating labile marine (kOM,M ~0.7 yr-1 (R. C. Aller et al., 1996; R. C. Aller & Blair, 2006)) and refractory terrestrial (low reactivity, kOM,T = 0.1 kOM,M, arbitrary slower) organic matter with slightly different composition (table 1, Supplementary Data S1). OM degradation was partitioned along the characteristic succession of terminal electron acceptor using formulations of established diagenetic models (table S2: Boudreau, 1996; Van Cappellen & Wang, 1996):

R_{OM,G} = \sum_{TEA}^{N_{TEA}}{k_{OM,G}X_{OM,G}f(TEA)} \tag{7}

where XOM,G is the molar concentration (M) of the respective particulate organic matter pool G. f(TEA) is one or a sum of Monod-type and inhibition term(s) related to a specific metabolic pathway (Boudreau, 1996) (table S2). Parameter values were taken from (Boudreau, 1996) without alterations, and initial tests demonstrated that these parameters have little effects. However, here we refer to the ‘reactive’ fraction of residual MnO2 and Fe(OH)3, which is calculated similar to a reactive continuum approach (Postma, 1993): (Xi/Xi,0)r = (Xi/Xi,0)γ. In the absence of reasonable constraints, a wide range of values for γ (1–750) were tested. In addition, sulfate-mediated anaerobic oxidation of methane (AOM) was included (Martens & Berner, 1977; Y. Wang & Van Cappellen, 1996).

3.2. Inorganic reactions from established diagenetic models

Reduced metabolites from OM degradation may react to form carbonate, sulfide, or phosphate minerals, or be re-oxidized. Because re-oxidized Fe3+ rapidly (minutes) precipitates as Fe(OH)3 upon oxidation (Stumm & Morgan, 2013), Fe3+ is ‘scavenged’ in the model with a rate constant of 0.25 yr-1 (Rp,Fe(OH)3 in M/yr, (Raiswell & Canfield, 2012))

R_{Fe(OH)_{3}} = 0.25\left\lbrack Fe_{tot}^{3 +} \right\rbrack \tag{8}

Dissolution of Fe(OH)3 and MnO2 proceeds solely via dissimilatory manganese and iron reduction (DMR and DIR, respectively) in our model. Dissolution (Rd, M/yr) and precipitation rates (Rp, M/yr) of carbonates and sulfides (Van Cappellen & Wang, 1996), and precipitation of phosphates (M. Zhao et al., 2020) and opal-CT (cf. Khalil et al., 2007), were described by first-order (p = q = 1) kinetics with respect to the specific mineral saturation state Ω (with mineral subscript, dropped for simplicity in equations but implied in reactant-product sets), except calcite, which follows variable orders of dissolution (depending on Ωcal) and high order during precipitation (Sulpis et al., 2022).

\mathrm{\Omega} = \frac{\prod_{C}^{N_{C}}\left\{ C \right\}^{\nu_{C}}}{K_{SP}}\tag{9}

R_{d} = k_{d}X(1 - \mathrm{\Omega})^{p}\tag{10}

R_{p} = k_{p}(1 - \mathrm{\Omega})^{q}\tag{11}

{C} is the activity of a solute C, Nc the total number of solutes, and KSP, kd and kp are the particle-specific solubility constant (subscripts dropped here for simplicity), dissolution constant (yr-1) and precipitation constant (M/yr) of the particle in question (assuming {Xi}= 1). In our time-evolving model runs, Ω values vary widely, from strong undersaturation to supersaturation for most phases included. The initial parameters were chosen according to experiments and field observations (Sulpis et al., 2022; Y. Wang & Van Cappellen, 1996; M. Zhao et al., 2020; Supplementary Data S1) and were then scaled to approximate the observations from the Amazon delta (section 3.6).

3.3. Dissolution and transition state theory

Silicate dissolution kinetics were described by ‘linear’ transition state theory (TST) (Aagaard & Helgeson, 1982; Hellevang et al., 2013; Heřmanská et al., 2022, 2023):

R_{TST} = RSA\sum_{m}^{N_{m}}{A_{m}e^{\frac{{- E}_{a,m}}{RT}}}\prod_{C}^{N_{C}}\left\{ C \right\}^{n,c}(1 - \mathrm{\Omega})\tag{12}

where RSA is the reactive and accessible surface area of a particle relative to solution volume (m2/L), commonly approximated by geometric constraints or by gas adsorption techniques and a unitless correction factor (Heřmanská et al., 2022; Marty et al., 2015; Wallmann et al., 2023). Here we calculated bulk surface areas from individual mineral volumes using densities (g/m3) and gas adsorption-measured specific surface areas (m2/g, Supplementary Data S1). Estimating the reactivity and accessibility of the so calculated surfaces is a long-standing and unsolved problem in geosciences and chemistry. RSA estimates are complicated by its time and scale dependence, and by textural relationships, but is commonly accounted for by applying a (unitless) correction factor in the order of 0.1–10-5 (e.g., Beckingham et al., 2017; Maher et al., 2006; Schnoor, 1990; White & Brantley, 2003). Consistent with the theoretical and observational constraints of comparably high reaction rates in marine settings (Geilert et al., 2023; Gruber et al., 2019; Michalopoulos & Aller, 1995; Wallmann et al., 2023), we chose a relatively high factor of 0.1, i.e., 10 % of the bulk surface area of a given mineral is assumed to be reactive at the relevant timescales (except bSi, which is assumed to be twice as reactive as abiotic opal-A, table 2). is an Arrhenius term (Am: Arrhenius constant (mol/m-2yr-1), Ea,m: apparent activation energy of m (J/mol), R: universal gas constant (Jmol-1K-1), T: absolute temperature (K)) describing the temperature dependence of reaction mechanism m. Ea,m reflects the energetic barrier to dissolution and regulates the temperature dependence of the dissolution rate. While incorporated in the model, temperature (27°C) was not varied, because activation energies were not available for all precipitation rates considered. {C}n,c reflects a dependence of mechanism m on the molar activity of species C (here exclusively {H+}, except for basaltic glass which is inhibited by dissolved Al) of order n. For vivianite, quartz, pyroxene and glauconite, no parameters for base-catalyzed dissolution (at high pH) and no parameters for neutral olivine and opal-CT dissolution were available (Heřmanská et al., 2022, 2023). However, the range of modelled pH values is comparably small (~7–8) so that the induced inaccuracy is rather limited. Dissolution of phosphates was also described in this way, although neither apatite nor vivianite dissolved under the modeled conditions.

TST has been criticized for its mechanistic inaccuracy (Müller et al., 2022; Truesdale & Greenwood, 2015), especially when dealing with mass transport-controlled reactions (R. A. Berner, 1980; Ruiz-Agudo et al., 2016), metastable substances (Müller et al., 2022) or complex textural relationships (Altree-Williams et al., 2015; Hellmann et al., 2012; Müller et al., 2022). For example, basaltic glass forms through rapid cooling of high temperature melts so that no actual equilibrium with the solution can exist. Thus, basaltic glass can dissolve independently from its ‘saturation state’. However, glass dissolution in our model ceases as amorphous silica becomes saturated. Despite all these pitfalls, currently available TST calibrations document the relative reactivities of different substances and their relationships to solution chemistry and temperature from a plethora of experiments conducted over decades (Aradóttir, Sonnenthal, & Jónsson, 2012; Heřmanská et al., 2022; Velbel, 1993). To date, TST-calibrated databases provide the only compilation of silicate dissolution kinetics across a wide range of settings and materials, and represent today’s standard in geoscientific and mineralogical research (Heřmanská et al., 2022; Palandri & Kharaka, 2004). Therefore, we use these TST rate laws to represent silicate and phosphate dissolution kinetics in our model.

3.4. Precipitation

Nucleation rather than growth may determine the overall precipitation rate during diagenesis (Wilkinson, 2015) and there is a ‘critical supersaturation’ at which stable authigenic nuclei can be formed (Kashchiev, 2011; Kashchiev & van Rosmalen, 2003), so that extension of TST towards supersaturation leads to extreme overestimation of precipitation rates (Hellevang et al., 2013). Thus, two different approaches to clay precipitation were tested: (I) a mechanistic, theory-based nucleation-growth law (Pham-Hellevang-Aagard, PHA) (Hellevang et al., 2013; Pham et al., 2011) and (II) a phenomenological Si-limited, pH-dependent composite batch rate law (Tosca-Isson-Planavsky, TIP) (Isson & Planavsky, 2018; Tosca et al., 2016). The PHA approach was also applied to carbonate precipitation, for which it has been tested successfully (Pham et al., 2011), while carbonates precipitate according to equation (11) in the TIP setup (table 1).

3.4.1. Nucleation-growth (PHA)

The PHA approach is based on a simplified form of classical nucleation theory combined with dislocation-controlled growth (Burton et al., 1949; Hellevang et al., 2013; Pham et al., 2011) and an additional term for Al(OH)3-limitation of Al-bearing clays (all except chrysotile) (rAl(OH)3, unitless, see ‘Al dynamics’ below):

\small{\begin{aligned} & R_{PHA}\\ & = \left( k_{g}RSA(\mathrm{\Omega} - 1)^{2} + k_{N}e^{\left( - \Gamma\left( \frac{1}{T^{1.5}\ln(\mathrm{\Omega})} \right)^{2} \right)} \right)r_{Al(OH)_{3}} \end{aligned}}\tag{13}

where kg is the growth constant (M m-2yr-1), kN the nucleation rate (M/yr) and Γ a functional factor that lumps together molar volume, a shape factor, and surface tensions of substrate and precipitate (Hellevang et al., 2013). While values of kg are available from seeded growth experiments (Marty et al., 2015; Yang & Steefel, 2008), kN and Γ are essentially unknown for most substances and situations, but experiments and sensitivity analyses indicate that Γ ~1–3 * 1010 for most clays, carbonates and opal (Hellevang et al., 2013). Although they allow for first order constraints on how variation of saturation during diagenesis drives precipitation dynamics, equation (13) does not directly reflect Si-limitation or pH-dependent kinetics (as opposed to indirect effects via Ω), which may be essential to marine and diagenetic weathering (Ehlert et al., 2016; Isson & Planavsky, 2018; Loucaides et al., 2010; Michalopoulos & Aller, 2004; Tosca et al., 2016; Tosca & Masterson, 2014).

3.4.2. Phenomenological silicate precipitation law (TIP): Si-limitation & pH-dependence

In addition to classical nucleation theory, we develop a novel, phenomenological silicate precipitation rate law that is based on previous studies of clay formation and reverse weathering (Isson & Planavsky, 2018; Tosca et al., 2016). This approach uses data from unseeded, anoxic batch experiments of homogeneously nucleated greenalite precipitation (Tosca et al., 2016) to empirically derive a batch precipitation rate law solely dependent on pH (note logarithmic scale) and dissolved Si concentration (Isson & Planavsky, 2018):

\begin{aligned} R_{TIP,max} &= k_{TIP}(pH)\left( \lbrack Si\rbrack - \lbrack Si\rbrack_{as}(pH) \right)\\ & = 1.01\ 10^{- 19}\ pH^{22.4}\left( \lbrack Si\rbrack - {2.02}^{- 5.57pH} \right) \end{aligned}\tag{14}

where kTIP(pH) (in yr-1) is a pH-dependent constant and [Si]as(pH) (in M) is a pH-dependent ‘asymptotic’ (low) Si concentration at which precipitation ceases. Although critiqued for its extreme pH dependence (Krissansen-Totton & Catling, 2020), this approach allows scaling of clay authigenesis directly to Si dynamics, while providing an upper limit of the pH-effect of OM diagenesis on silicate weathering. However, this rate law does not take mineral saturation states (Ω, eq 9) into account, i.e., if a driving force exists. Hence, it is strictly only applicable to systems that are a priori supersaturated enough to facilitate nucleation (Ω >> 10) and to the clay formed in the original experiments (greenalite). To be able to apply this rate law to different phases and conditions, we extended this empirical law by a critical saturation value and a tangens hyperbolicus term:

R_{TIP} = R_{TIP,max}\kappa_{1}\tanh\left( \frac{\kappa_{2}\frac{\mathrm{\Omega}}{\mathrm{\Omega}_{crit}}}{R_{TIP,max}} \right)r_{Al(OH)_{3}}\tag{15}

Similar to the PHA approach, rAl(OH)3 is a factor for Al(OH)3-limitation (see below), κ1 is a unitless scaling coefficient, and the factor κ2 (in M/yr) governs the dependence on saturation and ensures that the argument of the hyperbolic function becomes dimensionless. Given excess Al(OH)3 or dissolved Al (e.g., from feldspar dissolution): At high supersaturation the hyperbolic function yields 1, essentially representing RTIP,max (Isson & Planavsky, 2018; Tosca et al., 2016). This reflects an excess in driving force and rapid, pH-dependent reaction kinetics, so that the reaction becomes limited by the supply of Si to the site of precipitation via transport and coupled reactions (e.g., bSi or feldspar dissolution). At low supersaturation the hyperbolic function yields so that the rate becomes linearly dependent on supersaturation level hence on the chemical activity of its compounds and the resulting thermodynamic driving force. The rate becomes negligibly slow at low supersaturation Values for Ωcrit in the range of 106 to 109 were applied to the various secondary silicates, so that values of Ω between 10 and 104 are required to initiate quantitatively significant precipitation (table 2). Comparable composite rate laws have been introduced to address the observation of different dissolution mechanisms operating at different distances from equilibrium (Burton et al., 1949; Lasaga & Luttge, 2001; Sulpis et al., 2022). Similar to kN and Γ, κ1 and Ωcrit were scaled to observations from the Amazon delta and to induce competition among potential secondary silicates, while κ2 was held constant at 1 M/yr.

3.4.3. Aluminum dynamics and limiting concentrations

Resolving these ~ mM/yr major cation fluxes with an accuracy that complies with maximum Al concentrations of a few hundred nM is numerically (and analytically) challenging (Maher et al., 2006; Meister et al., 2022). Moreover, supply via dissolution of most detrital silicates, including plagioclase (Wallmann et al., 2023), is comparably slow (observations in the order of ~10–100 µM/yr), so that an additional, highly reactive source (and/or limit) of Al may be required to sustain authigenesis as inferred from Amazon delta porewater chemistry (Mackin, 1986; Michalopoulos & Aller, 2004). Besides Fe-Mn hydroxide-related Al (Mackin & Aller, 1984b), detrital Al-hydroxide (e.g., gibbsite, boehmite or amorphous) and/or (nanoparticulate) amorphous Al(-Si-Fe) phase(s) are alternative and potentially large sources of Al, mainly supplied via terrestrial weathering and subsequent erosion (e.g., Aplin & Taylor, 2012; Loucaides et al., 2010; Tsukimura et al., 2021). Detrital quartz and feldspar grains are often coated by clays and metal (oxy-)hydroxides that contain several weight percent of Al, depending on iron mineralogy (cf., Gibbs, 1973; Schwertmann & Taylor, 1989) and eventually inhibit the dissolution of the underlying grains (Beckingham et al., 2017). While amorphous nanoparticles are nearly invisible to many conventional techniques (Tsukimura et al., 2021), a more readily detectable, crystalline form of Al(OH)3, gibbsite, seems common in some of the southern lowland tributaries of the Amazon river (Gibbs, 1967). Thus, we introduce minor amounts (≤ 1 wt%, near the detection limit of crystalline silicates in standard X-ray diffractometry) of Al(OH)3, the dissolution rate (RAl [M Al/yr]) of which is constrained by a mass balance based on an empirical relationship between dissolved Al, Si and pH that appears to be widely applicable in mobile mud settings—strictly at pH > 7.3 and low ‘dissolved’ organic matter concentrations (see Mackin, 1986; Mackin & Aller, 1984c):

\begin{aligned} \lbrack Al\rbrack_{MA} &= 10^{- \left( 13.98 - 0.828\left\{ H^{+} \right\} - 0.429\lbrack Si\rbrack \right)}\\ & = \lbrack Al\rbrack - R_{Al}dt - \sum_{i}^{N_{sil}}{R_{i}\nu_{Al,i}dt} \leftrightarrow R_{Al}dt\\ & = \left( \lbrack Al\rbrack_{MA} - \lbrack Al\rbrack + \sum_{i}^{N_{sil}}{R_{i}\nu_{Al,i}dt} \right) \end{aligned}\tag{16}

where [Al]MA is the predicted dissolved concentration (Mackin & Aller, 1986). Strictly speaking, [Al]MA predictions are not corrected for log-transformation bias. Because of the good quality of the fit, standard deviation of residuals should be small so that the correction factor is close to 1. Thus, the error introduced is a constant offset to lower values in the order of a few % (i.e., at pM levels) and its influence on reaction patterns can be neglected given the many approximations and scaling procedures involved. Because limited supply of this particulate Al-source may restrict maximum precipitation rates, rAl(OH)3 (= XAl(OH)3/(XAl(OH)3)0) was introduced as a limiting factor for Al-clay precipitation in both, PHA and TIP rate laws (eqs 12, and 14).

Note that ‘Al(OH)3’ here represents an idealized model-phase, whose the composition and properties in nature are not very well defined. The various Al-sources (e.g., crustal aluminosilicates, clays and Al-Fe-Mn (oxy-)hydroxides, coatings) and their relative contribution to clay authigenesis and alkalinity cycling require more analytical in-depth research. Comparable, but less dynamic approaches have been implemented into previous diagenetic models to tackle a similar problem and a lack of measurements (Maher et al., 2006; Meister et al., 2022). The approach and parameter values are strictly only valid at pH > 7.3 and in Amazon delta-like sediments with relatively low Fe2+ concentrations (Mackin, 1986; Mackin & Aller, 1986), possibly affecting aluminosilicate saturation under various conditions. If Al is not excessively consumed, it is allowed to deviate from this relationship, i.e., it can rise if aluminosilicate dissolution fluxes exceed those of clay formation. Moreover, if consumption at the calculated reaction rate of any phase would exceed the dissolved reservoir, it is set to 10% of that solute concentration, resembling concentration-limited precipitation similar to RFe(OH)3 (e.g., glauconite may become limited by Fe3+ under deeply ferruginous, Si-rich conditions) and preventing negative concentration errors.

3.5. Scenarios and strategy

We modeled two primary scenarios which represent time evolution of realistic end-member reactant mixtures: (I) a mobile mud layer at the Amazon delta topset facies (Amz) that incorporates pre-weathered terrigenous sediment (largely clay, quartz, Mn-Fe (oxy-)hydroxides and smaller amounts of feldspar), marine organic matter, and biogenic silica, and (II) a comparably un-weathered, mafic sediment approximating Icelandic rivers in a similar depositional setting (Ice) (fig. 2, table 1). These model end-members were complemented by additional intermediate scenarios and a sensitivity analysis. Only input sediment concentrations were adjusted in these scenarios, all other parameters were kept constant and both model setups (TIP & PHA, table 1) were applied to each scenario.

First, we model a mobile mud layer at the Amazon delta topset facies (Amz) that stabilizes for a characteristic timescale of ~6 months (McKee et al., 2004). The input sediment composition approximates observations from Amazon River and delta sediments (table 1) (R. C. Aller et al., 1996; Gibbs, 1967; Michalopoulos & Aller, 2004; Poulton & Raiswell, 2002; Rousseau et al., 2019). The resulting rates and porewater concentrations were compared to some of the most detailed studies on mobile mud diagenesis and clay authigenesis conducted so far (R. C. Aller et al., 1996; R. C. Aller & Blair, 2006; Mackin & Aller, 1986; Michalopoulos et al., 2000; Michalopoulos & Aller, 1995, 2004; Rude & Aller, 1989; Spiegel et al., 2021; Wallmann et al., 2023; Z. Zhu et al., 2002). Kinetic constants were first initialized within the range of published values (table 2) and then adjusted manually (within an order of magnitude, table 2) to match the observed porewater concentrations and estimated reaction rates in the Amazon delta topset facies.

A (pseudo-)first-order rate constant with respect to organic matter (OM) degradation was taken from literature (R. C. Aller et al., 1996; R. C. Aller & Blair, 2006), and MnO2 and FeOH3 reactivity coefficients were adjusted to roughly match Mn2+ and Fe2+ concentrations and facilitate sustained ferruginous conditions in the Amz scenario. Silicate dissolution kinetics were then scaled using a (high) surface reactivity constant (0.1) that is common to all silicates, preserving relative reactivities except for bSi, to account for the complex shapes and highly reactive surfaces of fresh biogenic silica compared to pre-weathered and abiotic amorphous silica (Van Cappellen et al., 2002). A reactivity scaling factor of two for bSi dissolution was required to harmonize relatively stable, sub-millimolar Si concentrations with net K and Mg consumption at a ~ mM/yr scale later on. Carbonate, phosphate and sulfide dissolution were practically irrelevant and have not been scaled. Carbonate precipitation was scaled to match observed dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) and Mn concentrations at the given OM degradation rate, and facilitate competition among the various carbonate minerals. First order (with respect to saturation) carbonate precipitation constants are about an order of magnitude lower than in previous diagenetic models (Y. Wang & Van Cappellen, 1996), possibly due to the higher number of carbonates included (four instead of two) and different thermodynamic databases used. First order (with respect to saturation) phosphate precipitation rates constants were decreased by a factor 0.01 relative to literature values (of carbonate-fluor apatite), preventing negative P concentration errors and facilitating P storage by authigenic minerals in the order of magnitude of P release (Ruttenberg, 1992). The first order rate constant of FeS precipitation of ~5 ×10-5 was found adequate, rapidly consuming Fe2+ upon sulfate reduction as observed in nature, and is about a factor three higher than previously applied values (Y. Wang & Van Cappellen, 1996). Silicate precipitation was significantly more difficult to scale because sufficient constraints on relative nucleation and growth kinetics, or temperature and pH dependences are not available. Nucleation barriers were chosen to facilitate precipitation at the highest degrees of supersaturation during test runs, were adjusted to approximate observed porewater concentrations of K, Mg and Si, and to facilitate competition between different clay species. In the mechanistic nucleation growth setup, nucleation parameter choices were guided by published sensitivity analyses (Hellevang et al., 2013). The linear precipitation coefficients (mainly kN) were further adjusted to match the observed order of magnitude of K, Mg and Si consumption by clays, and pH changes. No reference data were available for our newly developed phenomenological clay precipitation rate law (TIP), so that the initial values of these parameters were chosen in comparison to the PHA parameters and improved iteratively. During the scaling procedure, the system appeared most sensitive to organic matter degradation and metal (oxy-)hydroxide reactivity, to clay nucleation barriers, and to the ratio of bSi and detrital silicate dissolution rate constants (in this order). Note that comparison to literature values is complicated for some parameters because of the different model environment (thermodynamic databases, ambient conditions, selected phase assemblages and reactants) or inadequate ranges (literature may not reflect the actual variability in nature). For the MnO2 and Fe(OH)3 reactivity parameters, our formulation differed substantially from the original use of the metal-oxide reactive continuum concept (Postma, 1993) (here coupled to OM degradation) impeding direct comparison.

After scaling, we explored the effects of terrestrial sediment sources and weathering intensity on diagenetic weathering (Michalopoulos & Aller, 2004; Trapp-Müller et al., in press; Wallmann et al., 2008, 2023), using a series of mixtures between an Amazon delta scenario (Amz), a highly weathered endmember, and a scenario approximating glaciated, Icelandic river sediments (Ice) (Poulton & Raiswell, 2002; Thorpe et al., 2019). A series of intermediate scenarios was created by linear mixing of the two endmembers to investigate the dynamic transition. Finally, we conducted a grouped linear global sensitivity analysis (see section Sensitivity analyses) to quantify the relative influences of OM, silicate, carbonate, and sulfide reaction kinetics on solute fluxes (H+, dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC), Ca, Mg, K, Si and Fe2+), at three time slices representing oxygenated, suboxic and anoxic conditions. Moreover, the global sensitivity analysis allows an estimation of the extent of interactions and nonlinearity in the model.

3.6. Global Sensitivity analyses

To quantify the sensitivity of solution chemistry (H+, DIC, Ca, Mg, K, Si, Fe2+) to different reaction groups (related to organic matter, silicate, carbonate and sulfides) we perturbed the corresponding rate laws linearly by pseudo-random factors (+/- 10 %) sampled from a Latin hypercube distribution (OM degradation: D OM, bSi dissolution: D bSi, inorganic silicate dissolution: D sil, silicate precipitation: P sil, carbonate precipitation: P carb, FeS precipitation: P FeS). For the sensitivity analysis, we used a reference scenario (30 % Amz- 70% Ice and γFe(OH)3 = 115) that allows observation of the transition from net reverse to forward weathering within a limited simulation time of 1 year in both model setups. As a quantitative measure for the influence of a process on a specific concentration change, Standardized Regression Coefficients (SRC) (Saltelli et al., 2008) are calculated by regressing the resulting concentration of an element of interest (Cdt) at a timestep of interest (here 1 day, 90 days and 325 days, reflecting oxygenated, suboxic and sulfidic conditions, respectively) against the perturbation factors of each process (PF) using a linear model:

\begin{aligned} C_{dt} &= I + \beta_{1}PF_{1} + \beta_{2}PF_{2} + \beta_{3}PF_{3}\\ & + \beta_{4}PF_{4} + \beta_{5}PF_{5} + e \end{aligned} \tag{17}

where I is the intercept, β the ordinary regression coefficient of a PF and e the error of approximation of Cdt. For well-performing models, β can be used to assess the influence of a specific PF on the model outcome. Scaling to the standard deviation of Cdt (σCdt) and PF (σPF) ensures that SRCs are independent of parameter units and scales.

SRC = \beta\frac{\sigma_{PF}}{\sigma_{C_{dt}}}\tag{18}

Positive values reflect an increasing influence, negative value reflect a decreasing effect. We express the relative contribution of each parameter to the model prediction as

SRC\% = 100\frac{SRC^{2}}{R^{2}}\tag{19}

In the following, we present and discuss SRC% and the direction of SRC. This method allows for robust sensitivity analysis in complex models with a limited number of runs (Saltelli et al., 2008; van Hoek et al., 2021). Given a reasonably good model performance, the ‘unexplained variability’ (100(1-R2)) quantifies the amount of nonlinearity and interactions, which is not accounted for in the simple linear model. However, the small size of the perturbations (< 10%) provokes a quasi-linear response over the studied range, ensuring a good quality linear fit. Stabilizing standard deviations of concentration changes demonstrate 200 runs were sufficient for the five perturbed groups in the chosen scenario for both, the TIP and PHA setups (figs. S5, S7).

4. Results

4.1. Tropical mobile muds

In mobile muds of the Amazon delta, porewater chemistry evolves systematically over ~3–9 months as indicated by the measurement-based red shading and arrows in figure 3. The kinetic parameters were roughly scaled to approximate these changes in porewater composition (fig. 3) and are summarized along with published reference values in table 2. The results also reproduce the dominant authigenic clay species identified in Amazon delta sediments (chlorite + ferrous, Si-rich mica) (Michalopoulos & Aller, 1995, 2004; Rude & Aller, 1989) with additional small amounts of illite and mixed-layer clays in the TIP scenario (figs. 4, S1). Moreover, the model reproduces the variation of authigenic mineral suites over the suboxic gradient in solution chemistry as detailed below. These parameter values were considered as a reference for subsequent model experiments. Generally, trends in solution chemistry are very similar in both model setups (PHA and TIP), but there are relatively small differences in pH, Si, Al, Mn2+ and Fe2+ concentrations (figs. 3–4, S1–S2). The differences are, however, less than an order of magnitude and rather affect the exact shape of the coupled trends.

OM is sequentially oxidized by O2 and NO3- within the first days, dominantly by MnO2 within weeks, and subsequently by mainly Fe(OH)3 with minor decreasing contributions of MnO2 and increasing contributions of SO42-, consistent with published estimates (R. C. Aller, 2004). This sequence of terminal electron acceptors (TEA) directly causes pronounced and systematic changes in first decreasing and then increasing pH, and increasing DIC, alkalinity, P, N(-III) (= NH4+ + NH3), and sequentially increasing Mn, Fe, S(-II) (= H2S + HS- + S2-), and CH4 concentrations. A total of ~3.5 mM and ~0.6 mM of marine and terrestrial organic carbon (~12 % and ~1.2 % of initial), respectively, are respired over a 6-month run, approximating the lower limit inferred from Amazon delta porewaters (R. C. Aller et al., 1996).

The evolution of porewater chemistry influences and is moderated by the dissolution of detrital and biogenic silicates, here mainly plagioclase, quartz and bSi (fig. 4). The corresponding solute accumulation (Si, Al, Na, K, Mg, Ca, Fe) and response of acid-base chemistry then determine the identity and rate of formation of inorganic precipitates, and net solute fluxes. The modelled P concentrations are consistent with those observed in the Amazon delta at relatively high Fe(OH)3 reactivity (low γFe(OH)3) and are largely moderated by apatite formation, which is generally consistent with a wide range of field observations, although inorganic/organic phosphorous ratios in Amazon shelf sediment are comparably low (R. A. Jahnke et al., 1983; Ruttenberg, 1992; Ruttenberg & Goñi, 1997). P levels vary largely as a function of pH for a given P release (kOm), hence, are governed by the amount and reactivity of metal (oxy-)hydroxides and by simultaneous silicate and carbonate reactions. Calcite dissolves upon acidification, more readily and rapidly with decreasing Fe(OH)3 reactivity (figs. 4, S2). Effects of pH on calcite dissolution seem to be stronger than those of DIC, so that calcite does not dissolve at high Fe(OH)3 reactivity, particularly in the PHA setup (fig. S2). Authigenic carbonate mineralogy transitions from kutnahorite (Mn-Ca) to ankerite (Fe-Mg-Ca-Mn) and, at high Fe(OH)3 reactivity, siderite (Fe) with their relative rates largely being set by dissolved Mn2+ and Fe2+ release from DMR and DIR (figs. 3–4). Siderite formation is more sensitive to Fe(OH)3 reactivity in the PHA setup, similar to calcite dissolution. These carbonate mineral patterns are consistent with inferences from stable carbon isotope ratios and sequential extractions in Amazon-derived sediments of the Amapá shelf (Z. Zhu et al., 2002). In our model, authigenic carbonates sequester ~15–50 % of the respired organic carbon, decreasing with Fe(OH)3 reactivity, approximating inferences from measurements in Amazon shelf sediments muds (~10–30 %) (R. C. Aller et al., 1996). Thus, the relative rates of OM degradation and carbonate precipitation dominate the evolution of DIC and alkalinity, and their interplay is moderated by Fe(OH)3 reactivity and the coupled effects of carbonate and silicate dissolution and of clay and sulfide precipitation on Fe2+, S(-II), the major cations and pH. The evolution of clay mineralogy follows the TEA sequence too: During aerobic and nitrogenous OM degradation smectite (montmorillonite and mixed-layer smectite) +/- illite precipitate relatively slowly (~0.1–1 mM/yr) and are subsequently outcompeted by a series of green clays (smectite + chrysotile glauconite (TIP only) + smectite Amazon clay + chlorite Amazon clay +/- smectite +/- illite) during DIR (fig. 4). The small individual stability fields of different green clay species depend largely on dissolved Fe2+/Fe3+ and pH (given sufficient dissolved Si and solid Al(OH)3 in these scenarios).

The chlorite stability field and related Mg consumption expand significantly with increasing Fe2+ supply and the corresponding increase in pH, while K consumption by the Amazon clay varies insignificantly over a wide range of Fe(OH)3 reactivities in both model setups (figs. 3–4, S1–S2). The sequence of green clay precipitation is more readily established in the TIP setup as glauconite and illite precipitation are muted by the stronger competetive effect in the PHA setup. While the difference in precipitation kinetics influence the shape of trends in pH, Si, Al, Mn2+ and Fe2+ levels, it is only marginally relevant to the overall changes in solution chemistry (figs. 3–4 and S1–S2). Green clays precipitate rapidly (up to15 mM/yr), exceeding experimental and leaching-based estimates of ~1.5 mM Fe2+-mica /yr (~2.8 µM K/g/yr (Michalopoulos & Aller, 2004)). However, such high green clay precipitation rates are required to fit the oberserved K decrease in porewaters Amazon delta (Michalopoulos & Aller, 2004; Spiegel et al., 2021). Because detrital plagioclase dissolution (~0.15 mM/yr) is about an order of magnitude slower than the observed green clay authigenesis under deeply ferruginous conditions, while quartz, K-feldspar and detrital clays quickly saturate, substantial amounts of Al(OH)3 are required to sustain this cation consumption (up to 80 mM/yr, fig. 4) in our model, implying acidification via reverse weathering (cf. Michalopoulos & Aller, 1995; Wallmann et al., 2023). Our predicted plagioclase dissolution rates approximate the upper limit estimated for plagioclase-rich, anoxic sediments off Iceland (< 0.1 mM/yr) (Maher et al., 2006) and exceed maximum forward weathering rates of anoxic mafic sediments in the Sea of Okhotsk (~0.01–0.015 mM/yr) (Wallmann et al., 2008). Because feldspar grains in pre-weathered, tropical sediments may become passivated by clay and metal (oxy-)hydroxide coatings, our model rate likely overestimates feldspar dissolution. Thus, the extent of Al(OH)3 consumption and related shifts to more reverse weathering seem plausible. However, during reduction, Fe-Mn-based coatings may dissolve, releasing Al and reactivating the underlying grain surfaces. Moreover, direct µm-scale feedback between dissolution and precipitation may allow for faster dissolution, even of nominally (super-)saturated detrital silicates (Ruiz-Agudo et al., 2016), such as K-feldspar and some detrital clay. As Fe2+ and pH decrease in response to precipitation, particularly of FeS, green clays eventually become undersaturated and the precipitating clay assemblage shifts back to a comparably slowly precipitating (0.1–0.3 mM/yr) aluminous clays (here dominantly illite and smectite in the PHA setup). The onset and duration of FeS precipitation and related acidification and modelled changes in authigenic mineralogy vary as a function of Fe(OH)3 reactivity (for a given kOmM) (figs. 3–4).

4.2. The role of terrestrial sediment sources and depositional timescale

For the given amount and reactivity of OM, the prevailing biogeochemical conditions at a given point in time vary primarily as a function of TEA availability and depositional timescale (figs. 3,5). Thus, terrestrial sediment sources, particularly metal (oxy-)hydroxide content, and the timescale of episodic reworking have a clear and dramatic effect on the evolution of the metabolic pathways of organic matter degradation, porewater composition and mineral authigenesis (fig. 5). Particularly DMR and DIR are regulated by metal (oxy-)hydroxides availability and exert a large effect on pH, mineral saturation states, weathering, and authigenesis (fig. 6). Moreover, sediment sources regulate the supply, composition and reactivity of detrital silicates. Both, metal (oxy-)hydroxide reduction and reactive detrital silicate supply affect the magnitude and direction of silicate weathering fluxes, and responses of authigenic carbonates, sulfide, phosphates, and porewater chemistry, also on interannual timescales (figs. 5–6). There is a fundamental difference in the late stage pH and Fe2+/S(-II) evolution of Fe(OH)3-rich and Fe(OH)3-poor scenarios upon sulfate reduction because FeS formation and related acidification eventually become limited by Fe2+ rather than S(-II) availability at low pre-weathering intensities (low %Amz). This condition allows for sulfide accumulation in solution, resulting in increases of pH and alkalinity that facilitates calcite precipitation (R. A. Berner et al., 1970; Boudreau & Canfield, 1993). The latter trend is consistent with global scale patterns of CaCO3 authigenesis in marine sediments (Schrag et al., 2013; Turchyn et al., 2021) and does not occur in Fe-rich, acidic scenarios, where calcite and siderite eventually dissolve during sulfate reduction (figs. 4, 6). This reflects a FeS-related bistability in the coupled Fe-S cycles, where small perturbations of OM/Fe(OH)3 input ratios within a specific critical range can fundamentally alter the systems biogeochemical state (van de Velde et al., 2020; Wijsman et al., 2002) and drive changes in weathering and authigenesis.

Generally, dissolved Mn and Fe concentrations and the duration of dominantly suboxic conditions increase with increasing pre-weathering intensity (%Amz), while dissolved Si, Na, K, Mg, K and P decrease. This is because higher amounts of Fe(OH)3 and Al(OH)3 allow for larger and more rapid Fe, Mn and related Al release, and inhibit the transition to sulfidic conditions. All of these factors are beneficial to green clay formation, element consumption and reverse weathering. However, K consumption within the modelled timeframe is maximized at ~75 %Amz, because of lower initial MnO2 concentrations and an earlier onset of DIR and transition to ferrous conditions, and a higher pH.

On the longer term, K consumption in the Amazon scenario would exceed that of the less pre-weathered scenarios, highlighting the role of depositional timescales. Higher amounts of mafic minerals and basaltic glass with decreasing %Amz increase the release of mainly Si and Mg and some K and Al, countering the effects of green clay formation on solution chemistry (fig. 6). The modelled dissolution rates of plagioclase, pyroxene and basaltic glass are comparable but slightly exceed those inferred from porewaters of anoxic mafic sediments (~0.01–0.1 mM/yr) (Maher et al., 2006; Wallmann et al., 2008). The modeled olivine dissolution rates coincide with those suggested for coastal environments (several mM/yr) (Montserrat et al., 2017). In the near Iceland scenario (figs. 5, S3), trends in Mg (post-ferruginous increase, ‘U-shaped’ at 25–50%Amz in fig. 5), K (stable to slight decrease), Ca (mM fluctuation, slight early increase and strong late-stage consumption), Si (rapid increase to opal saturation) and Al (slight increases at low %Amz in figs. 5, S3) resemble those in anoxic mafic sediment cores (Middelburg, 1990; Wallmann et al., 2008). Note that our approach to maintain Al mass balance at high clay precipitation rates approaches the limits of its validity limits (high Fe2+ or pH < 7.3) in some scenarios, reducing the accuracy of aluminosilicate saturation states.

Moderately pre-weathered sediments tend to Mg-K consumption, broadly consistent with observations from deeper (> 10 m below sediment surface) anoxic slope, fan and deep-sea sediments that are rich in feldspar and detrital clay (Aloisi et al., 2004; Meister et al., 2022; Torres et al., 2022; Wallmann et al., 2023). However, Mg-K consumption in these scenarios decreases by about an order of magnitude at the onset of sulfidic conditions (figs. 5, S3). The pattern emerges from the effect of evolving solution chemistry, particularly Fe2+ concentrations, that induce changes in the authigenic mineral assemblage from green clay to smectite-chrysotile +/- illite, and is intensified by decreasing Al(OH)3 availability in time. Thus, these patterns of weathering and related cation and alkalinity fluxes appear to be pre-determined by terrestrial sediment sources, but they emerge time-dependent in response to OM oxidation along the TEA sequence.

Specifically, decreasing Fe2+ and pH during later DIR and early sulfate reduction and an associated shift from green clay to aluminous clay precipitation facilitate the transition to alkalinity-neutral or net forward weathering and cation-release, particularly of Mg. The timing and shape of the transition from Mg consumption to Mg release strongly depend on precipitation kinetics and clay identity. High rates of chrysotile and smectite formation may significantly retard or even inhibit this transition, resulting in approximately stable Mg profiles. For example, depending on the relative rates of bSi and detrital silicate dissolution, and choices of clay nucleation barriers, Mg would not necessarily increase at 0%Amz, but only in the transitional, more acidic scenarios. Moreover, Mg-rich clays tend to precipitate in response to the dissolution of Mg-rich silicates, narrowing the net alkalinity impact. Forward weathering under basaltic-sulfidic conditions further raises pH and promotes carbonate formation. Only ~10% of the Ca consumed by calcite can be supplied by coeval detrital silicate dissolution (figs. 6, S3) so that the effect of silicate weathering on pH is more relevant to enhancing carbonate formation than the supply of Ca in our model. Again, reaction patterns are very similar in both model setups, but there are some differences in the details of evolution of carbonate and clay assemblages (illite, mixed-layer smectite), and in the shape of the trends in solution chemistry.

4.3. Sensitivity and interaction in the diagenetic reaction network

The previous section evaluated the sensitivity of the diagenetic reaction network towards the input of terrestrial minerals. Here, we present a linear analysis of the sensitivity of H+, DIC, Ca, Mg, K, Si, and Fe concentration changes to group-wise perturbations of reaction kinetics. As expected from the similarity of the reaction patterns modelled with the PHA and TIP setup, respectively, the model sensitivities are largely consistent (figs. 7, S5–S10). The unexplained variance (100 (1-R2)) is low (< 5 % in most cases, Fig. S10) and implies limited non-linear effects over small perturbation ranges (+/- 10%) ranges. However, early-stage Ca, K, Mg and late-stage K and H+ seem to be affected by significant non-linearity (high unexplained variance), less so in the PHA than in the TIP setup. These relationships reflect a specific situation and cannot necessarily be quantitatively extrapolated to other particle input mixtures and depositional environments. However, the general trends appear to be robust, compared to observations.

The sensitivity analysis revealed a strong response of dissolution and precipitation reactions to the non-linearity of OM degradation pathways with time (figs. 8, S10). We present in detail three time slices that are representative for oxic ([O2] ≥ 1 μM; day 1), suboxic ([O2] < 1 μM, Mn-Fe dominated; day 70) and sulfidic conditions ([O2] < 1 μM, total [S(-II)] > 1 μM; day 325; figs. 7–8, S5–S9). Besides a major influence of OM degradation, silicate weathering processes (dissolution of bSi (D bSi) and detrital silicates (D Sil) and precipitation of silicates (P Sil)) dominate major cation and Si concentration patterns, and details of pH evolution particularly under suboxic and sulfidic conditions (fig. 8). Fe and Ca concentration responses are complex and drivers vary substantially in time. DIC is primarily influenced by the rate of organic matter degradation. In the following, we will examine the details of these reaction dynamics.

Under oxygenated conditions (day 1), H+, DIC and Ca increase (pH decreases) primarily in response to aerobic OM oxidation. Although calcite remains supersaturated, Ca concentrations increase with organic matter degradation rates due to exchange with NH4+ at surface sites, and with detrital silicate dissolution (pyroxene, plagioclase). Moreover, detrital silicate dissolution increases Mg and K concentrations and decreases H+ by ~20 %, i.e., forward weathering partly buffering acidification through aerobic respiration (fig. 8). In the TIP setup, K decreases in response to increasing detrital silicate dissolution and significant non-linearity is involved, reflecting effects on illite saturation and cation exchange. Si increases are largely driven by bSi dissolution in both setups, while Fe concentrations increase in response to detrital silicate dissolution and OM degradation equally.

During the suboxic, Fe2+-dominated stage (70 days), H+ levels are primarily regulated by decreases through detrital silicate dissolution and increases through clay precipitation (PHA, fig. S10) and/or bSi dissolution (TIP, fig. 8), resulting in slightly net forward weathering. Forward weathering under suboxic conditions is facilitated by the presence of basaltic reactants, especially olivine, but is strongly reduced by the acid effects of bSi dissolution coupled to silicate (green clay) precipitation. DIC and Ca are still dominated by the rate of OM degradation and forward detrital silicate weathering that together lower Ca concentration by enhancing calcite saturation. A significant effect of linear carbonate precipitation rate coefficients on Ca is evident under suboxic conditions in the TIP setup (fig. 8). Moreover, bSi dissolution appears to slightly reduce Ca sequestration, probably by increasing the reverse component of the net silicate weathering balance. Mg concentrations under suboxic conditions are dominated by the interplay of detrital and biogenic silica dissolution, the latter promoting K-rich over Mg-rich clay precipitation. In the TIP setup, the effect of bSi dissolution on clay concurrence is much weaker and detrital silicate dissolution exerts a stronger positive influence on Mg concentrations. In both setups, K consumption is clearly dominated by the beneficial effect of bSi dissolution on the precipitation of the Si-rich Amz clay. Dissolved Si levels during the suboxic stage are largely governed by the balance of bSi dissolution and authigenic silicate precipitation. Fe concentrations mainly decrease with detrital and biogenic silicate dissolution, implying a stronger sensitivity of Fe sequestration to silicate than to carbonate processes.

Under sulfidic conditions (325 days), H+ concentrations decrease primarily in response to detrital silicate dissolution, reflecting net forward weathering. OM degradation and bSi dissolution slightly increase H+ as they stimulate FeS, smectite and chrysotile formation, respectively (fig. S10). In the TIP setup, this also applies to carbonate (calcite) precipitation rates (fig. 8). This is also reflected in Ca decreases that are primarily driven by the positive influence of OM degradation and detrital silicate dissolution on calcite saturation. DIC concentrations still increase primarily with increasing OM degradation rates, but detrital silicate dissolution now exerts a minor negative influence reflecting silicate-carbonate coupling in the PHA setup (fig. S10). OM degradation and bSi dissolution seem to limit increases of Mg under sulfidic conditions by increasing the clay sink through pH and Si increases, while detrital silicate dissolution and carbonate precipitation appear to elevate Mg through direct Mg release and competitive effects of calcite and siderite (fig. 8). In both setups, K concentrations increase in response to OM degradation, reflecting the concurrence of OM-driven FeS formation and silicate precipitation, and increase in response to bSi dissolution, promoting sequestration in silicates (figs. 8, S10). However, in the TIP setup, a strong influence of silicate precipitation is indicated directly along with strong non-linear and/or interaction effects (~40% unexplained fraction, fig. S10), possibly reflecting the hyperbolic function regulating the dependence on saturation in the TIP rate law. However, such a high unexplained fraction renders the linear model insufficient for quantitative evaluation. Late-stage Si levels increase with bSi dissolution and, slightly, with OM degradation, and decrease with increasing detrital (alumino-)silicate dissolution. This is because detrital silicate dissolution releases Si, Al, and alkalinity, driving silicate precipitation, while acidification through organic matter degradation and reverse weathering of bSi inhibit clay formation (relative to Si release). Finally, late-stage Fe concentrations decrease in response to increasing OM degradation and coupled FeS precipitation, with a positive effect of bSi dissolution, reflecting concurrence with the less efficient clay sinks, in both setups.

5. Discussion

5.1. Links between organic matter, authigenic minerals and silicate weathering