1. INTRODUCTION

There is general consensus that the eastern margin of Laurentia resulted from Neoproterozoic extension and breakup of supercontinent Rodinia (e.g., Bradley, 2008; Hoffman, 1991; Li et al., 2008; Macdonald et al., 2023; Pisarevsky et al., 2003; all ages follow Cohen et al., 2013, v. 2023/09). However, the timing and plate tectonic processes responsible for the separation of eastern Laurentia from Baltica, Amazonia, and intervening terranes continue to be the subject of debate. One of the popular scenarios calls for Tonian to Ediacaran rift evolution to have culminated with ca. 570 Ma breakup and opening of Iapetus Ocean, followed by 540–535 Ma rifting along eastern Laurentia that featured the dispersal of peri-Laurentian microcontinental blocks, opening of the Humber (Taconic) Seaway, and creation of the eastern Laurentian or Humber passive margin (fig. 1A, e.g., Cawood et al., 2001). Although some Neoproterozoic rift events may have involved mantle plume-like activity (e.g., Kamo et al., 1995; Tegner et al., 2019), late Ediacaran rift stages included depth-dependent extension (Allen et al., 2009, 2010; Thomas, 1991, 1993) that resulted in hyper-thinned crust and exhumed continental mantle lithosphere analogous to that observed in modern magma-poor margins (Chew & van Staal, 2014; Macdonald et al., 2014; van Staal et al., 2013). van Staal et al. (2013) proposed that eastern Laurentian rift evolution included a hanging-wall block that developed into an isolated microcontinent, named Dashwoods, outboard of the Humber Seaway during late Ediacaran hyperextension and mantle exhumation. The magma-poor rift model of van Staal et al. (2013) called for ca. 565–550 Ma exhumation processes in western Newfoundland to reflect ultra-slow spreading and opening of the Humber Seaway and concurrent development of a mid-ocean ridge system in west Iapetus on the outboard side of Dashwoods. Robert et al. (2021) proposed a model that further characterized ca. 720 Ma rifting of Laurentia-Amazonia and opening of the Puntoviscana Ocean, ca. 600 Ma rifting of Laurentia-Baltica and opening of eastern Iapetus, and ca. 550 Ma hyperextension and opening of western Iapetus without coeval seafloor spreading in the Humber Seaway inboard of Dashwoods. Although hypotheses for the timing and nature of lithospheric breakup vary, there has been some agreement that post-rift thermal subsidence along the eastern Laurentian passive margin was delayed 20–30 Myr because of the insulating effects of sedimentary cover, structural emplacement of hot mantle, thermal expansion of plate margin segments with thick crust, or other factors (Allen et al., 2010; Macdonald et al., 2023; van Staal et al., 2013). Seismic stratigraphic and field studies of modern passive margins have instead proposed that magma-poor rifts have discrete phases of crustal and mantle breakup and corresponding isostatic adjustment and deposition of breakup sequences prior to thermal subsidence (Alves & Cunha, 2018; Soares et al., 2012), but these stratigraphic concepts have not yet been universally applied to ancient passive margin systems (e.g., Beranek, 2017).

Ediacaran to lower Cambrian rocks assigned to the Labrador and Curling groups comprise the exposed base of the Humber margin in western Newfoundland, Canada, and are well suited to characterize the rift evolution of eastern Laurentia based on constraints from targeted sedimentological, biostratigraphic, and regional bedrock mapping studies (figs. 1B, 2, 3, e.g., Cawood et al., 2001; Cawood & van Gool, 1998; James & Debrenne, 1980; Knight & Boyce, 2014; Lavoie et al., 2003; van Staal & Barr, 2012; Williams & Hiscott, 1987). Published (Cawood & Nemchin, 2001) and unpublished (e.g., Allen, 2009 in White & Waldron, 2022) detrital zircon U-Pb studies have used SIMS (secondary ion mass spectrometry) and LA-ICP-MS (laser ablation-inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry) techniques, respectively, to interpret the provenance of Labrador and Curling group strata, but these low-n datasets (<60 grains/sample) may not provide robust evaluations of maximum depositional age, regional correlations, or tectonic significance. For example, there remains disagreement about basal Labrador and Curling group strata that unconformably overlie crystalline basement rocks and rift-related lavas being the result of syn-rift tectonic subsidence (White & Waldron, 2022; Williams & Hiscott, 1987), deposition during the rift-drift transition (Cawood et al., 2001), or post-rift thermal subsidence (Lavoie et al., 2003; Macdonald et al., 2023). In this article, we report new detrital zircon U-Pb-Hf isotope results and detrital mineral percentages of Labrador and Curling group sandstones to investigate the establishment of the Humber passive margin. Our detrital zircon studies include high-n LA-ICP-MS datasets that facilitate statistical assessments using MATLAB routines. The new data are integrated with published stratigraphic constraints for western Newfoundland to evaluate Humber margin evolution and provide testable models for the development of the Humber Seaway. We use evidence from modern magma-poor rift systems to propose a plate tectonic model which calls for the establishment of the Humber passive margin to include Ediacaran to Cambrian breakup sequences that record the transition from breakup tectonism to thermal subsidence. We summarize Ediacaran-Cambrian rift evolution in the southern Caledonian-northern Appalachian orogen and propose that the Scotland-Ireland and SE Canada-NE United States segments of eastern Laurentia also contain crustal and mantle breakup sequences.

2. EDIACARAN TO CAMBRIAN STRATIGRAPHY

Neoproterozoic to lower Paleozoic rocks of the Humber passive margin are integral parts of the northern Appalachian orogen in New England and Atlantic Canada (fig. 1A, e.g., James et al., 1989; Waldron & van Staal, 2001); the northern continuation of the Humber passive margin into the southern Caledonides is demonstrated by broadly equivalent rock units in Ireland and Scotland (e.g., upper Dalradian Supergroup: Prave et al., 2023; Strachan & Holdsworth, 2000). In western Newfoundland, ca. 950–1500 Ma crystalline rocks of the Grenville Province (Pinware terrane) represent the distal edge of the Laurentian craton and are the depositional substrates for Humber margin successions (Cawood & van Gool, 1998; Heaman et al., 2002; Hodgin et al., 2021). Labrador and Curling group strata that are the focus of this study, as well as underlying Proterozoic crystalline basement rocks, were variably affected by Cambrian-Ordovician (Taconic), Silurian (Salinic), Devonian (Acadian), and later deformation events associated with the Appalachian orogenic system (e.g., Cawood, 1993; Cawood et al., 1994; White & Waldron, 2019). Labrador Group strata are exposed in the weakly deformed Laurentian autochthon, whereas coeval Laurentian rocks of the Curling Group are assigned to the Humber Arm allochthon and were transported westwards and emplaced onto platformal successions as a result of convergent margin tectonism (e.g., Lavoie et al., 2003; Waldron et al., 1998; Waldron & Stockmal, 1991). Fleur de Lys Supergroup strata comprise polydeformed and metamorphosed rocks that are equivalents of Labrador and Curling group strata in west-central Newfoundland (fig. 2A, e.g., Cawood & Nemchin, 2001; Hibbard, 1983). The eastern edge of the Humber margin system is generally marked by the Baie Verte-Brompton line (figs. 1A, 2A), a long-lived fault zone in part defined by ophiolitic fragments that are juxtaposed against Fleur de Lys Supergroup strata (e.g., van Staal & Barr, 2012).

The Humber margin is interpreted to include promontories and embayments framed by transform faults that are orthogonal to rift zones (fig. 1B, e.g., Allen et al., 2009, 2010). The promontories generally have thin Paleozoic successions, narrow thrust belts, and complex deformation of basement massifs, whereas the embayments have thicker stratigraphic successions with wider thrust belts and fewer exposed basement massifs (Thomas, 1977, 1991). The Humber passive margin in Newfoundland is part of the St. Lawrence promontory and segmented by the Serpentine Lake, Bonne Bay, Canada Bay, and Belle Isle transform fault systems (figs. 1B, 2A, 2B, Allen et al., 2009, 2010; Cawood & Botsford, 1991; Williams, 1979). Mafic to felsic igneous rocks in the St. Lawrence promontory and Quebec embayment, including those along the Serpentine Lake, Bonne Bay, and Sept Îles transforms (fig. 1B), yield ca. 615–600 Ma and ca. 580–550 Ma crystallization ages that constrain the timing of rift-related extension which ultimately resulted in the birth of the Humber passive margin (fig. 1B, e.g., Macdonald et al., 2023). Other evidence for the timing of rift-related deformation in the northern Appalachians is derived from ca. 614–613 Ma pseudotachylytes from the Montmorency fault (St. Lawrence rift system) in southern Quebec that separate Proterozoic gneiss from lower Paleozoic strata (O’Brien & van der Pluijm, 2012) and 761–582 Ma zircon (U-Th)/He cooling ages for Proterozoic crystalline rocks on Anticosti Island (Powell et al., 2018) that were exhumed during regional extension.

2.1. Labrador Group

Labrador Group rocks are the stratigraphic archives of early Humber margin development in the Laurentian autochthon (e.g., James et al., 1989; Lavoie et al., 2003). The lowermost Labrador Group succession in southern Labrador and the Great Northern Peninsula and Belle Isle regions of NW Newfoundland consists of Bateau Formation shale, siltstone, cross-bedded sandstone, and conglomerate units up to 244 m-thick that unconformably overlie Proterozoic gneiss and are intruded by rift-related mafic rocks correlated with the ca. 615 Ma Long Range dike swarm (figs. 2A, 3, Bostock et al., 1983; Kamo et al., 1989; Williams & Hiscott, 1987; Williams & Stevens, 1969). Lighthouse Cove Formation basalt lavas fed by Long Range dike sources are up to 310 m-thick and overlie both Bateau Formation and Proterozoic gneiss units in the Belle Isle area (fig. 3, Williams & Hiscott, 1987; Williams & Stevens, 1969).

The lowermost Labrador Group succession in SW Newfoundland consists of massive to tabular to trough cross-bedded feldspathic sandstone and conglomerate units of the Bradore Formation that unconformably overlie Proterozoic crystalline rocks (fig. 3, e.g., Williams, 1985). Equivalent Bradore Formation strata in southern Labrador and the Belle Isle region unconformably overlie both Proterozoic gneiss and Lighthouse Cove Formation volcanic rocks (figs. 2A, 2B, e.g., Bostock et al., 1983; Cawood et al., 2001). Detailed sedimentological studies of the Bradore Formation have reported fluvial, tidal-influenced marine, and shallow-marine shelf deposits with northeast- to east-directed paleocurrent indicators (e.g., Hiscott et al., 1984; James et al., 1989; Long & Yip, 2009). Bostock et al. (1983) noted that the Bradore Formation in the Belle Isle area ranges from 10 to 175 m-thick and is locally exposed in the hanging-walls of basement-involved normal faults, implying that it was deposited during extensional deformation. The precise timing and tectonic significance of Bradore Formation deposition are uncertain; the basement-cover unconformity at the base of the unit was proposed by Cawood et al. (2001) to reflect the rift-drift transition in the Laurentian autochthon, whereas Williams and Hiscott (1987) and Allen et al. (2010) concluded that there is an unmapped unconformity somewhere higher in the Bradore Formation that marks the onset of passive margin sedimentation. Landing and Bartowski (1996) and Landing (2012) correlated the Bradore Formation with Cambrian Series 2 strata of the U.S. Appalachians that overlie Proterozoic rocks and have lower Olenellus biozone faunas. The upper units of the Bradore Formation yield Dolopichnus, Conichnus, Skolithos linearis, Lingulichnus verticalis, and other trace fossils that are generally consistent with early Cambrian depositional ages (Hiscott et al., 1984; James et al., 1989; Long & Yip, 2009; Pemberton & Kobluk, 1978). Bradore Formation sandstone has yielded ca. 930–1223 Ma detrital zircon grains with a 1124 Ma age peak (1 sample, n = 53, Cawood & Nemchin, 2001), which supports sedimentological evidence for the unit to have provenance from underlying and adjacent Proterozoic crystalline rocks in western Newfoundland.

The Forteau Formation conformably overlies the Bradore Formation in southern Labrador and western Newfoundland (fig. 3, e.g., James et al., 1989; Knight et al., 2017). The type section in southern Labrador includes basal dolomite overlain by shale, fossiliferous sandy limestone, and calcareous siltstone and sandstone (Schuchert & Dunbar, 1934). The Forteau Formation varies in thickness by region; shelf successions of an inboard, western facies belt in Labrador are <120 m-thick, whereas deep-water successions of an outer, eastern facies belt in western Newfoundland are up to 700 m-thick (Riley, 1962) and represent a major depocenter that is not well understood in the lower Paleozoic platform-slope system (Knight, 2013). This west-to-east facies transition is generally supported by paleocurrent indicators observed in shelf strata (e.g., Knight et al., 2017). The lower Forteau Formation, in addition to the upper parts of the underlying Bradore Formation, are interpreted to comprise a transgressive systems tract during early thermal subsidence along the Humber passive margin (e.g., Lavoie et al., 2003). A maximum flooding surface is marked by a shale-dominated interval above the lower limestone unit, and upper shale, burrowed siltstone, and sandstone show the onset of a highstand systems tract that eventually gave way to a prograding carbonate shelf (Skovsted et al., 2017). Dated parts of the Forteau Formation are Cambrian Series 2 (Stages 3–4) based on Bonnia-Olenellus biozone fossils, Archaeocyathan fauna, and other assemblages (Boyce, 2021; James & Debrenne, 1980; Knight et al., 2017; Skovsted et al., 2017). Detrital zircon studies of the Forteau Formation have not been completed because of the abundance of carbonate and fine-grained siliciclastic rocks in the unit and therefore the provenance of its strata with respect to the underlying Bradore Formation is uncertain.

The Hawke Bay Formation conformably overlies the Forteau Formation in southern Labrador and western Newfoundland (fig. 3, James et al., 1989; Schuchert & Dunbar, 1934). The Hawke Bay Formation mostly consists of massive to planar cross-stratified quartz arenite with minor glauconitic sandstone, shale, and bioturbated limestone units that are up to 250 m-thick. Hawke Bay Formation lithofacies, ichnofauna, and west-southwest and east-northeast-directed paleocurrent indicators support a high-energy wave and storm-dominated shoreface environment (e.g., Knight & Boyce, 2014). Representative fauna from the Mesonacis bonnensis, Glossopleura, Polypleuraspis and other biozones indicate that the Hawke Bay Formation is Cambrian Series 2 (Stage 4) to early Miaolingian (Wuliuan) and deposited during a eustatic sea-level lowstand at the end of the Sauk I subsequence (Knight & Boyce, 2014; Lavoie et al., 2003; A. R. Palmer & James, 1980). Hawke Bay Formation sandstone has yielded ca. 955–2835 Ma detrital zircon grains with 1043, 1854, and 2780 Ma age peaks (1 sample, n = 64, Cawood & Nemchin, 2001), which indicate provenance from Archean cratons and flanking Proterozoic orogens of eastern Laurentia.

Upper Cambrian (Ehmaniella cloudensis biozone) to Lower Ordovician platformal carbonate successions (Port au Port and St. George groups) overlie the Labrador Group and are the youngest units of the Humber passive margin (e.g., James et al., 1989). Middle Ordovician carbonate and shale units in western Newfoundland (Table Head Group) heralded faulting and erosion of the Laurentian platform and were succeeded by the west-directed passage of a forebulge and flysch deposition related to Taconic orogenesis (e.g., Knight et al., 1991; Waldron et al., 2003).

2.2. Curling Group

Curling Group rocks comprise Laurentian margin strata of the Humber Arm allochthon, which is one of the west-transported allochthons in western Newfoundland (figs. 2, 3, e.g., Williams & Cawood, 1989). The Blow Me Down Brook Formation occupies the highest thrust sheet of the Humber Arm allochthon in the Bay of Islands area (Woods Island succession of Waldron et al., 2003) and likely represents the most distal unit of the Curling Group. The Blow Me Down Brook Formation mostly consists of micaceous feldspathic to lithic arenite with minor quartz arenite, conglomerate, and shale that together are >370 m-thick. The lithostratigraphic features of the unit are consistent with deposition by sediment gravity flows (S. E. Palmer et al., 2001). Red mudstone of the Blow Me Down Brook Formation overlies and is interbedded with Ediacaran(?) pillowed to massive basalt and breccia in several localities (e.g., Gillis & Burden, 2006; Waldron et al., 2003; Williams & Cawood, 1989), but elsewhere, overlying units contain Oldhamia (Lindholm & Casey, 1990; see Herbosch & Verniers, 2011) and acritarch species (Burden et al., 2001, 2005; S. E. Palmer et al., 2001) that indicate late Terreneuvian to Cambrian Series 2 (Stage 4) to Wuliuan age constraints for the unit. The composite Blow Me Down Brook Formation succession may therefore correlate with several Labrador Group units of the Laurentian autochthon, including Forteau and Hawke Bay formations of the early passive margin. Blow Me Down Brook Formation sandstone has yielded ca. 1019–3592 Ma detrital zircon grains with 1057, 1841, and 2784 Ma age peaks (1 sample, n = 55, Cawood & Nemchin, 2001) that indicate provenance ties with Proterozoic and Archean rocks of the eastern Laurentian hinterland.

The Summerside Formation occupies an intermediate thrust sheet of the Humber Arm allochthon in the Humber Arm area (Corner Brook succession of Waldron et al., 2003) and includes ~700 m of quartz to feldspathic arenite and shale units that comprise submarine fan deposits (fig. 3, e.g., S. E. Palmer et al., 2001). The base of Summerside Formation is not exposed, but it is interpreted to unconformably overlie Proterozoic crystalline basement (Cawood & van Gool, 1998; Waldron et al., 2003). Summerside Formation strata contain Ediacaran to early Cambrian spheromorph acritarchs and other palynomorph assemblages (S. E. Palmer et al., 2001) and may comprise a rift-related unit correlative with the lowermost Labrador Group and lower parts of the Blow Me Down Brook Formation (e.g., Lavoie et al., 2003). Summerside Formation sandstone has yielded ca. 580-1186 Ma detrital zircon grains with 1012 Ma and 1129 Ma age peaks (1 sample, n = 54, Cawood & Nemchin, 2001) that demonstrate provenance from rift-related, Neoproterozoic igneous rocks and underlying and adjacent Proterozoic crystalline basement units.

The Irishtown Formation (Brückner, 1966) conformably overlies the Summerside Formation and consists of shale, quartz arenite, and conglomerate units with a structural thickness >1100 m (fig. 3, S. E. Palmer et al., 2001). Irishtown Formation strata contain flute casts, load structures, and partial to complete Bouma sequences that indicate deposition by turbidity currents and debris flows (Cawood & van Gool, 1998; S. E. Palmer et al., 2001). Granite, sandstone, shale, and limestone clasts with early Cambrian fossils, especially those in conglomerate units deposited along the Bonne Bay transform, indicate derivation from Proterozoic crystalline basement and Labrador Group sources (e.g., Cawood & van Gool, 1998). The upper Irishtown Formation contains early Cambrian acritarchs (S. E. Palmer et al., 2001) that suggest correlation with the Forteau or Hawke Bay formations and upper parts of the Blow Me Down Brook Formation (e.g., Lavoie et al., 2003). However, detrital zircon studies of the Irishtown Formation have not been completed and these proposed stratigraphic correlations are untested. Mid- to upper Cambrian to Middle Ordovician deep-water carbonate rocks (Northern Head Group) unconformably overlie the Irishtown Formation and are probable time-equivalents to passive margin successions (Port au Port and St. George groups) of the Laurentian autochthon (fig. 3, e.g., Cawood & van Gool, 1998).

2.3. Fleur de Lys Supergroup

Fleur de Lys Supergroup metaclastic rocks exposed in the Corner Brook Lake area of west-central Newfoundland overlie Mesoproterozoic orthogneiss and rift-related Ediacaran intrusive rocks (Mount Musgrave Group – MM in fig. 3, e.g., Cawood & Nemchin, 2001; White & Waldron, 2022). Equivalent successions in the Baie Verte Peninsula comprise parts of a cover sequence on top of Mesoproterozoic gneiss (WB – White Bay Group in fig. 3, e.g., Hibbard, 1983, 1988; Hibbard et al., 1995) and an early Tonian volcanic-sedimentary succession (Strowbridge et al., 2022). Fleur de Lys Supergroup lithologies in the Baie Verte Peninsula region include metaconglomerate, marble breccia, and psammitic and pelitic schists that are interlayered with mafic metavolcanic rocks (e.g., Hibbard, 1988; Hibbard et al., 1995). Birchy complex units in the Coachman’s Cove area of the Baie Verte Peninsula (fig. 2A) are part of an Ediacaran (ca. 564–556 Ma) rift succession and contain serpentinized peridotite, gabbro, mafic schist, and metasedimentary rocks that locally contain detrital chromite from nearby ultramafic sources (van Staal et al., 2013). Flat Point Formation psammite, interpreted as cover to the Birchy complex (fig. 3), has yielded ca. 1026, 1075, 1305, 1480, and 1883 Ma age peaks (1 sample, n = 69, van Staal et al., 2013), and Fleur de Lys Supergroup mica schist elsewhere in the Baie Verte Peninsula has yielded ca. 1050, 1150, 1361, 1501, and 2478 Ma age peaks (1 sample, n = 78, Willner et al., 2014). These detrital zircon U-Pb results are interpreted to reflect provenance from Archean and Proterozoic rocks of eastern Laurentia (e.g., Willner et al., 2014).

3. METHODS AND MATERIALS

3.1. Sampling strategy

Sandstone samples of the Labrador and Curling groups were collected using bedrock geological maps and stratigraphic reports as guides (see location information in fig. 2B and tables 1, S1, and S2). Well exposed stratigraphic sections with fossil constraints were targeted and measured by Jacob staff when possible (Soukup, 2022). Labrador Group samples comprise: (1) Bradore Formation sandstone units collected <10 m above the unconformity with Proterozoic crystalline rocks in the Bonne Bay and Indian Head Range areas (Williams, 1985; Williams & Cawood, 1989; Williams & Hiscott, 1987); and (2) Hawke Bay Formation sandstone units from Marches Point in the Port au Port Peninsula (Knight & Boyce, 2014). Curling Group samples comprise: (1) Blow Me Down Brook Formation sandstone units in the Bay of Islands (Candlelite Bay) and Bonne Bay (South Arm) areas (Burden et al., 2005; Lindholm & Casey, 1990; Williams & Cawood, 1989); (2) Summerside Formation sandstone units along Humber Arm (S. E. Palmer et al., 2001); and (3) Irishtown Formation sandstone collected along Humber Arm and in the Bonne Bay area (S. E. Palmer et al., 2001).

3.2. Scanning Electron Microscope – Mineral Liberation Analysis

Quantitative mineral studies of 38 thin sections (Bradore Formation: n = 1, Hawke Bay Formation: n = 13, Blow Me Down Brook Formation: n = 20, Summerside Formation: n = 2, Irishtown Formation: n = 2) were conducted at Memorial University of Newfoundland using a FEI Quanta field emission gun (FEG) 650 scanning electron microscope (SEM) equipped with Mineral Liberation Analysis (MLA) software version 3.14 (Beranek et al., 2022; Grant et al., 2018; Sylvester, 2012). Area percentage values for each sample are provided in table S1; the results reported in Section 4 highlight only the key mineral constituents in each sample. Instrument conditions included a high voltage of 25 kV, working distance of 13.5 mm, and beam current of 10 nA. SEM-MLA maps were created using GXMAP mode by acquiring Energy Dispersive X-Ray spectra in a grid every 10 pixels, with a spectral dwell time of 12 ms, and comparing these against a list of mineral reference spectra. The MLA frames were 1.5 mm by 1.5 mm with a resolution of 500 pixels x 500 pixels.

3.3. Detrital zircon U-Pb geochronology and Hf isotope geochemistry

Laser ablation U-Pb and Hf isotope studies of 11 sandstone samples (Bradore Formation: n = 2, Hawke Bay Formation: n = 2, Blow Me Down Brook Formation: n = 3, Summerside Formation: n = 2, Irishtown Formation: n = 2) were conducted at Memorial University of Newfoundland using a Thermo-Finnigan Element XR single-collector ICP-MS and Thermo-Finnigan Neptune multi-collector ICP-MS, respectively. Laser ablation methods, isotopic results, and reference material values are reported in table S2. Photographs of field sample sites are provided in figure S1. Time-integrated U-Pb and Hf analyte signals were analyzed offline using Iolite software (Paton et al., 2011). U-Pb ages were calculated using the VizualAge data reduction scheme (Petrus & Kamber, 2012). Concordance values were calculated as the ratio of 206Pb/238U and 207Pb/206Pb ages and analyses with high error (>10% uncertainty) or excessive discordance (>10% discordant, >5% reverse discordant) were excluded from maximum depositional age estimates and provenance interpretations. The reported ages for grains younger and older than 1200 Ma are based on 206Pb/236U and 207Pb/206Pb ages, respectively.

U-Pb dates are reported at 2 uncertainty and shown in probability density plots made with the AgeCalcML MATLAB program (Sundell et al., 2021). The modes for each sample are informally reported as probability age peaks. Initial 176Hf/177Hf are reported as εHf(t) and represent isotopic compositions at the time of crystallization relative to the chondritic uniform reservoir (CHUR). Initial epsilon Hf (εHf[t]) calculations used the decay constant of Söderlund et al. (2004) and CHUR values of Bouvier et al. (2008). Age-corrected epsilon Hf (Hf[t]) vs. U-Pb age plots were made with the Hafnium Plotter MATLAB program of Sundell et al. (2019). Maximum depositional ages were estimated with the Maximum Likelihood Age algorithm of Vermeesch (2021). U-Pb and U-Pb-Hf statistical assessments reported in table S3 were conducted with the DZstats (Saylor & Sundell, 2016) and DZstats2D (Sundell & Saylor, 2021) MATLAB programs, respectively. Multi-dimensional scaling (MDS) plots were made with the DZmds (Saylor et al., 2018) and DZstats2D (Sundell & Saylor, 2021) MATLAB programs.

4. RESULTS

4.1. Labrador Group

4.1.1. Bradore Formation

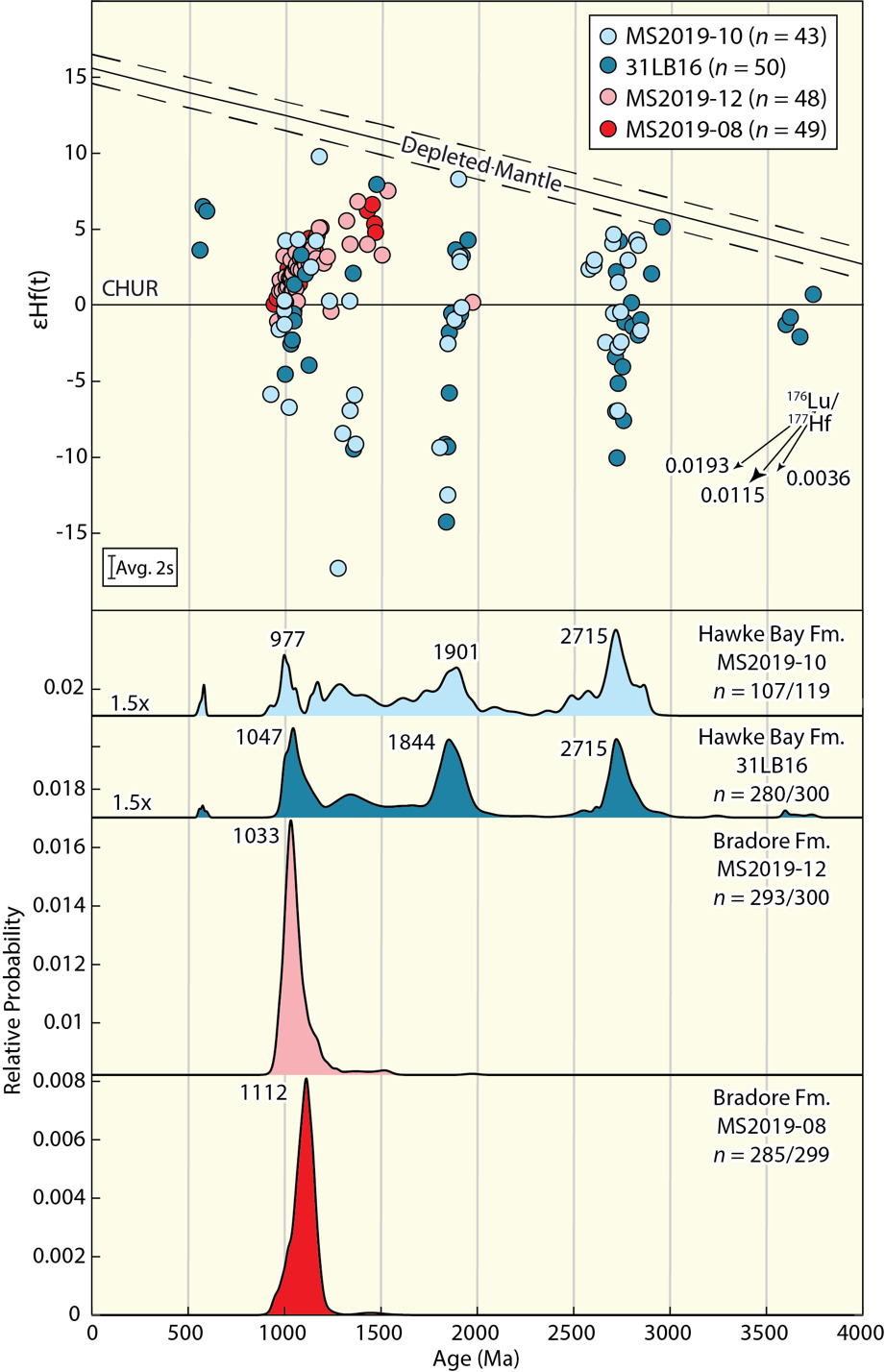

Feldspathic sandstone (78% quartz, 13% potassium feldspar) that overlies Mesoproterozoic orthogneiss units in the Indian Head Range contains the highest ilmenite (0.54%), titanite (0.77%), and zircon (0.11%) values in the sample suite (sample MS2019-08 in table S1). This sample yields 281 detrital zircon grains (~99%) that range from 943 ± 13 Ma to 1247 ± 34 Ma and comprise a 1112 Ma age peak and four grains (~1%) from 1427 ± 47 Ma to 1469 ± 52 Ma (sample MS2019-08 in fig. 4). Quartz sandstone that overlies Mesoproterozoic granite in the Bonne Bay area yields 286 detrital zircon grains (~98%) that range from 953 ± 24 Ma to 1377 ± 44 Ma and comprise a 1033 Ma age peak, five grains (~2%) from 1427 ± 61 Ma to 1533 ± 36 Ma, and one (<1%) 1972 ± 35 Ma grain (sample MS2019-12 in fig. 4). Tonian to Stenian and Ectasian to Calymmian detrital zircon grains in the Bradore Formation have εHf(t) values that range from -1.0 to +5.1 = +2.4) and -0.4 to +7.5 = +4.6), respectively (fig. 4).

4.1.2. Hawke Bay Formation

Quartz arenite to subfeldspathic sandstone units (83–97% quartz, 3–10% potassium feldspar) from Marches Point have notable magnetite (<0.01–0.35%), rutile (0.01–0.04%), and tourmaline (<0.01–0.03%) contents (samples PAP16_HB-1, -2A, -3A, -4A, -5, -6, -7, -8, -9, -10, -16B in table S1); other rocks are glauconitic and limy sandstone units (samples PAP16_HB11, MS2019-10 in table S1). A lower quartz sandstone from Marches Point yields three grains (~1%) from 559 ± 7 Ma to 594 ± 10 Ma, 62 grains (~22%) that range from 989 ± 21 Ma to 1167 ± 23 Ma and comprise a 1047 Ma age peak, 129 grains (~46%) that range from 1247 ± 43 Ma to 1972 ± 50 Ma and include an 1844 Ma age peak, five grains (~2%) from 2052 ± 35 Ma to 2451 ± 57 Ma, 73 grains (~26%) that range from 2524 ± 42 Ma to 2954 ± 31 Ma and comprise a 2715 Ma age peak, and five (~2%) grains from 3243 ± 33 Ma to 3737 ± 23 Ma (sample 31LB16 in fig. 4). An upper, glauconitic sandstone from Marches Point yields 566 ± 7 Ma and 583 ± 6 Ma detrital zircon grains, 12 grains (11% ) that range from 926 ± 17 Ma to 1068 ± 20 Ma and comprise a 977 Ma age peak, 50 grains (~47%) that range from 1134 ± 12 Ma to 1975 ± 22 Ma and include a 1901 Ma age peak, four grains (~4%) from 2077 ± 40 Ma to 2366 ± 33 Ma, and 39 grains (~36%) that range from 2460 ± 26 Ma to 2872 ± 24 Ma and include a 2715 Ma age peak (sample MS2019-10 in fig. 4). Ediacaran detrital zircon grains in the Hawke Bay Formation have εHf(t) values that range from +3.6 to +6.5 = +5.5). Tonian to Stenian, Orosirian, and Neoarchean age peaks that comprise most of the Hawke Bay Formation samples have εHf(t) values of -6.7 to +9.8 = +0.1), -14.2 to +8.3 = -2.1), and -20.0 to +4.7 Ma = -1.9), respectively.

4.2. Curling Group

4.2.1. Blow Me Down Brook Formation

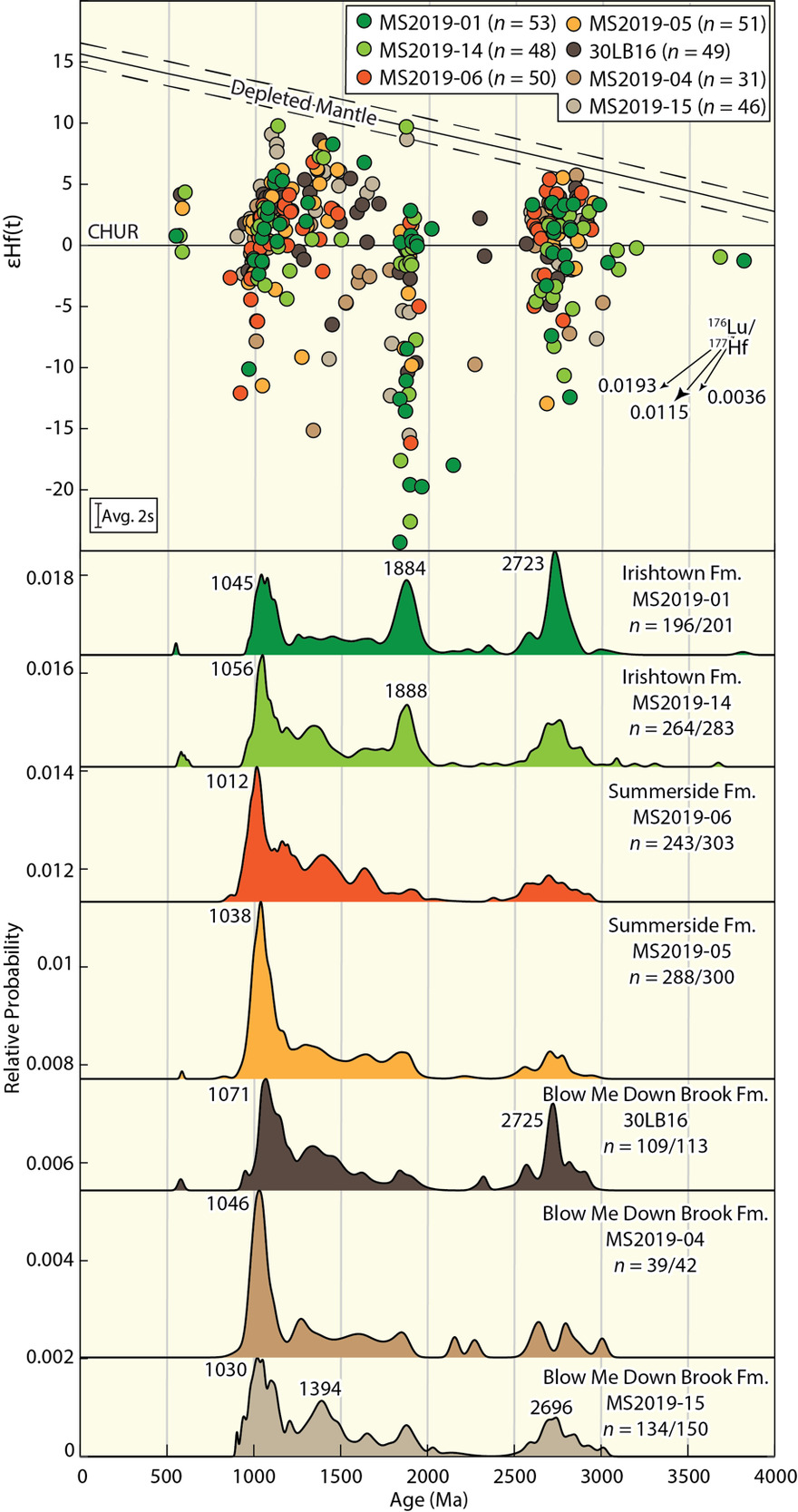

Blow Me Down Brook Formation sandstone units are micaceous and feldspathic (0.09–11.27% muscovite, 0.04–10.63% potassium feldspar) and have albite (9.22–23.63%) and chlorite (0.22–7.73%) alteration and trace garnet (0.01–0.16%) and ilmenite (<0.01–0.08%) contents (samples MS2019-04 and -15, 30LB16, BOI16_B2, -B3a, -B3b, -B4, -B5, -B6, -B7, -B8, -B8b, -B9, -B10, -B11, -B12, -B13, -B14, -B15, -B16 in table S1). Micaceous feldspathic sandstone along the South Arm of Bonne Bay yields 47 detrital zircon grains (~35%) that range from 902 ± 6 Ma to 1173 ± 39 Ma and include a 1030 Ma age peak, 61 grains (~46%) that range from 1201 ± 16 Ma to 2177 ± 87 Ma and include a 1394 Ma age peak, and 26 grains (~19%) that range from 2569 ± 61 Ma to 3016 ± 20 Ma and include a 2696 Ma age peak (sample MS2019-15 in fig. 5). Quartz sandstone from the Bay of Islands yields 17 detrital zircon grains (~44%) that range from 948 ± 58 Ma to 1147 ± 28 Ma and comprise a 1046 Ma age peak, 13 grains (~33%) from 1236 ± 41 Ma to 1866 ± 36 Ma, 2157 ± 25 Ma and 2271 ± 28 Ma single grains (~5%), and seven grains (~18%) from 2616 ± 44 Ma to 3006 ± 27 Ma (sample MS2019-04 in fig. 5). Feldspathic sandstone interbedded with MS2019-04 quartz sandstone yields a 579 ± 16 Ma detrital zircon grain (<1%), 76 grains (~70%) that range from 947 ± 14 Ma to 1931 ± 79 Ma and include a 1071 Ma age peak, 2300 ± 33 Ma and 2326 ± 18 Ma grains (~2%), and 30 grains (~28%) that range from 2493 ± 58 Ma to 2914 ± 21 Ma and include a 2725 Ma age peak (sample 30LB16 in fig. 5). The single Ediacaran grain sample 30LB16 has an εHf(t) value of +4.0. Tonian to Stenian, Ectasian to Calymmian, and Neoarchean ages that make up most Blow Me Down Brook Formation samples yield εHf(t) values of -7.8 to +9.0 = +2.2), -15.1 to +8.5 = +1.2), and -4.9 to +3.9 = +0.5), respectively.

4.2.2. Summerside Formation

Summerside Formation quartz sandstone units have notable albite (21.91% 22.78%), garnet (0.02%, 0.03%), muscovite (0.05%, 3.42%), rutile (0.19%, 0.32%), and zircon (0.03%, 0.05%) contents (samples MS2019-05, -06 in table S1). A lower quartz sandstone unit from Pettipas Point along Humber Arm yields a 586 ± 9 Ma detrital zircon grain (<1%), 144 grains (50%) that mostly range from 920 ± 20 Ma to 1190 ± 22 Ma and comprise a 1038 Ma age peak, 107 grains (~37%) from 1216 ± 27 Ma to 1904 ± 42 Ma, 2208 ± 40 Ma to 2239 ± 61 Ma grains (<1%), and 35 grains (~12%) from 2497 ± 60 Ma to 2952 ± 34 Ma (sample MS2019-05 in fig. 5). An upper quartz sandstone from Pettipas Point yields 104 grains (~43%) that mostly range from 917 ± 11 Ma to 1197 ± 9 Ma and comprise a 1012 Ma age peak, 102 grains (~42%) from 1202 ± 26 Ma to 2090 ± 81 Ma, and 37 grains (~15%) that mostly range from 2495 ± 38 Ma to 2935 ± 20 Ma. (MS2019-06 in fig. 5). The single Ediacaran grain in sample MS2019-05 has an εHf(t) value of +2.9. Tonian to Stenian age peaks that make up most of the Summerside Formation samples yield εHf(t) values of -12.1 to +6.0 = -0.4), whereas subsidiary Ectasian to Orosirian and Neoarchean age groups have εHf(t) values of -16.2 to +8.0 = 0.0) and -13.0 to +5.4 = +0.6), respectively.

4.2.3. Irishtown Formation

Irishtown Formation sandstones are quartz-rich (88.44%, 93.33%) and include minor albite, ankerite, chlorite, and muscovite (samples MS2019-01, -14 in table S1). Quartz sandstone from a unit with pebble to cobble clasts of granite, sandstone, and fossiliferous limestone in the Bonne Bay area yields 569 ± 8 Ma, 583 ± 6 Ma, 599 ± 7 Ma, and 620 ± 11 Ma detrital zircon grains (~2%), 77 grains (~29%) that range from 947 ± 12 Ma to 1192 ± 18 Ma and comprise a 1056 Ma age peak, 117 grains (~44%) that range from 1199 ± 38 Ma to 1999 ± 25 Ma and include a 1888 age peak, three grains (~1%) from 2145 ± 26 Ma to 2391 ± 25 Ma, 60 grains (~23%) from 2474 ± 78 Ma to 3194 ± 24 Ma, and two (<1%) 3310 ± 23 Ma to 3675 ± 18 Ma grains (MS2019-14 in fig. 5). Quartz sandstone along Humber Arm yields a 552 ± 8 Ma grain (<1%), 45 grains (~23%) from 970 ± 10 Ma to 1195 ± 35 Ma and comprise a 1045 Ma age peak, 79 grains (~40%) that range from 1249 ± 20 Ma to 2021 ± 61 Ma and include a 1884 age peak, six grains (~3%) from 2145 ± 35 Ma to 2361 ± 38 Ma, 64 grains (~33%) that range from 2526 ± 28 Ma to 3079 ± 68 Ma and include a 2723 Ma age peak, and one (<1%) 3816 ± 34 Ma grain (MS2019-01 in fig. 5). Four Ediacaran detrital zircon grains have εHf(t) values of -0.6 to +4.2 = +1.2). Tonian to Stenian, Orosirian, and Neoarchean age peaks that make up most Irishtown Formation samples have εHf(t) values of -4.5 to +9.6 = +1.3), -24.6 to +9.6 = -6.2), and -10.7 to +3.4 = -1.2), respectively.

5. INTERPRETATION

5.1. MDA estimates and timing of Ediacaran-Cambrian deposition along the Humber margin

5.1.1. Labrador Group

Bradore Formation sandstones above the basement-cover unconformity in western Newfoundland yield Tonian (970 ± 7 Ma, 971 ± 5 Ma) MDA estimates that are ca. 450 Myr older than the depositional ages proposed for the unit based on marine ichnofacies (Hiscott et al., 1984; Long & Yip, 2009; Pemberton & Kobluk, 1978) and correlations with lower Olenellus biozone units in the U.S. Appalachians (Landing, 2012; Landing & Bartowski, 1996), respectively (table 1). We therefore interpret that our Bradore Formation samples were deposited between 970 Ma and 509 Ma based on the MDA calculations and Cambrian Series 2 fossils in overlying strata of the Forteau Formation (e.g., Skovsted et al., 2017). In this interpretation, the MDA estimates are much older than the true depositional age and indicate Ediacaran to early Cambrian erosion of underlying or adjacent crystalline rocks during extensional deformation and filling of local structural basins (e.g., Bostock et al., 1983). The age range of the Bradore Formation is relevant because some plate tectonic models have proposed that the switch from syn-rift to passive margin deposition is recorded by the unconformity at the base of the Bradore Formation (Cawood et al., 2001) or a speculative unconformity somewhere within the Bradore Formation (Allen et al., 2010; Williams & Hiscott, 1987) that would potentially divide the unit into lower and upper successions of different ages. If the latter model is correct, one solution is that a lower, unfossiliferous succession sampled herein comprises an unconformity-bounded unit of pre-Cambrian Series 2 strata, whereas an upper succession consists of Cambrian Series 2 (~519–509 Ma) strata with marine ichnofauna and ties to Olenellus biozone units elsewhere in the Appalachians. The current outcrop exposure of the potential lower succession in western Newfoundland is uncertain, but we predict it is of mappable extent and at least several tens of meters thick. We propose that targeted field and sediment provenance studies are necessary to fully examine these relationships and interpret the physical stratigraphy and tectonic significance of lower Bradore Formation rocks.

Carbonate and siliciclastic rocks of Forteau Formation are entirely within the Bonnia-Olenellus biozone and argue for the transition to passive margin deposition by the late early Cambrian (James et al., 1989; Lavoie et al., 2003) or Stage 4 of Cambrian Series 2 (~514 Ma, Knight et al., 2017). In combination with the storm-dominated shoreline deposits of the upper Bradore Formation, the lower and middle units of the Forteau Formation were deposited as parts of eastward-deepening, shelf-to-basin succession during eustatic sea-level rise and development of a transgressive systems tract that resulted in a maximum flooding surface and highstand system tract (Sauk I subsequence, Knight et al., 2017). Hawke Bay Formation shoreface to shelf deposits that conformably overlie the Forteau Formation yield Ediacaran (562 ± 9 Ma, 567 ± 44 Ma) MDA estimates and are ca. 50 Myr older than the Cambrian Series 2 (Stage 4) to early Miaolingian (Wuliuan) fossil ages proposed for the unit (table 1). Hawke Bay Formation strata are generally linked to regression and a sea-level lowstand near the boundaries of the Sauk I and Sauk II subsequences (e.g., A. R. Palmer & James, 1980), however, Landing et al. (2024) proposed that these rocks may comprise siliciclastic bypass shelf or highstand system tract deposits. Regardless, our results indicate that quartz-rich strata of the Hawke Bay Formation yield Ediacaran to Archean detrital zircon grains that are older than the time of sediment accumulation, which is consistent with continent-scale drainage and sediment recycling along the Humber margin by 514–505 Ma (cf., Cawood et al., 2012). Hawke Bay Formation strata are overlain by upper Cambrian carbonate shoals and tidal flat strata that formed northeast-trending facies belts and deepened towards the southeast (James et al., 1989).

5.1.2. Curling Group

Feldspathic and quartz sandstone from Oldhamia- and acritarch-bearing successions of the Blow Me Down Brook Formation that overlie mafic volcanic rocks in the Bay of Islands (Burden et al., 2005; Gillis & Burden, 2006; Lindholm & Casey, 1990; S. E. Palmer et al., 2001) yield Ediacaran (586 ± 21 Ma) and Stenian (1002 ± 15 Ma) MDA estimates, respectively (table 1). Micaceous feldspathic sandstone from an Oldhamia-bearing succession in the Bonne Bay area (Lindholm & Casey, 1990) yields a Tonian (902 ± 11 Ma) MDA estimate (table 1). Herbosch and Verniers (2011) conducted a global review of Oldhamia occurrences. They hypothesized that Blow Me Down Brook Formation ichnofauna are consistent with Cambrian Series 2 (Stage 4) to early Miaolingian depositional ages but acknowledged that these age assignments were influenced by proposed correlations with the Forteau and Hawke Bay formations of the Labrador Group. Acritarchs in the Blow Me Down Brook Formation (Skiagia, Comosphaeridium, Annulum squamaceum, Fimbriaglomerella membrancea, and others; Burden et al., 2001; S. E. Palmer et al., 2001) instead suggest late Terreneuvian to Cambrian Series 2 (Stage 4) depositional ages for the unit using the reference frames of Moczydłowska (1991) and Moczydłowska and Zang (2006), but these microfossils could be recycled and overestimate the true depositional age. Our Blow Me Down Brook Formation samples, likely collected from the upper parts of the unit, were therefore deposited between ca. 529 Ma and 504 Ma based on the available late Terreneuvian to early Miaolingian fossil constraints. In this interpretation, the MDA estimates are much older than the time of sediment accumulation and indicate early Cambrian erosion of Ediacaran and older igneous rocks or their supracrustal derivatives (cf., Cawood et al., 2012). However, basal turbidite units of the Blow Me Down Brook Formation are interbedded with mafic lavas correlative with ca. 551 Ma Skinner Cove Formation volcanic rocks (see Cawood et al., 2001). The Blow Me Down Brook Formation may therefore contain an unrecognized unconformity that separates a lower succession with ca. 551 Ma mafic volcanic and siliciclastic rocks from an upper succession of lower Cambrian siliciclastic rocks. Palmer et al. (2001) recognized such a potential lower succession in the Bay of Islands region that is of mappable extent and at least several tens of meters thick.

Quartz sandstone units of the Summerside Formation yield Ediacaran (595 ± 10 Ma) and Tonian (889 ± 19 Ma) MDA estimates (table 1). Palmer et al. (2001) reported that large, granular sphaeromorph acritarchs in these successions are consistent with late Precambrian depositional ages, but also noted that the microfossils may have been recycled into Curling Group strata during the early Cambrian. For example, overlying Irishtown Formation quartz sandstone units with Ediacaran (556 ± 12 Ma, 574 ± 10 Ma) MDA estimates (table 1) also contain these large sphaeromorph acritarchs and yield the late Terreneuvian to Cambrian Series 2 (pre-Bonnia-Olenellus biozone; Moczydłowska & Zang, 2006) microfossils Annulum squamaceum and Fimbriaglomerella membrancea(?) that are recognized in the Blow Me Down Brook Formation. We interpret that the Ediacaran and Tonian MDA estimates for the Summerside and Irishtown Formations are older than the true depositional ages of the rock units, and based on published lithostratigraphic correlations with the upper Labrador Group (e.g., Lavoie et al., 2003), are Cambrian Series 2 to early Miaolingian in age.

5.2. Sediment provenance

Ediacaran detrital zircon grains comprise 0–2% of our samples (<1% of dataset) and are sourced from rift-related igneous rocks in the St. Lawrence promontory (fig. 1B; see compilation by Macdonald et al., 2023). For example, 566 Ma and 586–579 Ma age groups in the Blow Me Down Brook, Summerside, Irishtown, and Hawke Bay formations are similar in age to the 564 Ma Birchy complex schist in the Baie Verte Peninsula (van Staal et al., 2013) and 565 Ma Sept Îles intrusion (Higgins & van Breemen, 1998) and 583 Ma Baie des Moutons complex (McCausland et al., 2011) in the Quebec Appalachians. Other Ediacaran age fractions in our samples overlap in uncertainty with 551 Ma Skinner Cove Formation volcanic rocks (Cawood et al., 2001), 555 Ma Lady Slipper tonalite (Cawood et al., 1996), and ca. 607 Ma Hare Hill granite and Disappointment Hill tonalite (Hodgin et al., 2021) in SW Newfoundland, 581–576 Ma Blair River dikes in Cape Breton Island (Miller & Barr, 2004), and 615 Ma Long Range dikes in NW Newfoundland and Labrador (Kamo et al., 1989). Ediacaran detrital zircon grains accordingly have chondritic to superchondritic Hf isotope compositions that are consistent with igneous rocks sourced from the partial melting of metasomatized lithospheric mantle during extension or contamination of asthenospheric mantle-derived magmas with Proterozoic crust (e.g., Miller & Barr, 2004; Volkert et al., 2015). With the exception of the Bradore Formation samples underlain by crystalline basement, each of the units reported herein show Ediacaran contributions and six of the nine samples yield 595–556 Ma MDA estimates, which together demonstrates contributions from rift-related igneous rocks or their recycled derivatives. However, the low magnitude of Ediacaran grains in individual samples is probably the result of low zircon yield from mafic source rocks or much higher fertility of polycyclic, Tonian and older detrital zircon grains in the sedimentary system (cf., Cawood et al., 2012). Quartz-rich deposits of the Hawke Bay and Irishtown formations have the highest percentages of Ediacaran grains in the sample suite and indicate that Cambrian Series 2 to early Miaolingian sea level changes, recycling processes, and sediment transport delivered well-sorted sediment to both shoreface and submarine fan environments.

Early Neoproterozoic and Mesoproterozoic detrital zircon grains represent 1–12% (6% of dataset) and 29–91% of our samples (59% of dataset), respectively, and mostly indicate provenance from the eastern Grenville orogen (fig. 6; cf., Cawood & Nemchin, 2001). Our samples are characterized by 1110–970 Ma age peaks and ca. 1600–920 Ma age fractions that correspond with arc magmatism and accretionary events of the Labradorian (1680–1600 Ma), Pinwarian (1500–1450 Ma), Elzevirian (1250–1190 Ma), and Grenvillian (1190–980 Ma) orogenies and post-Grenvillian extension in western Newfoundland, southern Labrador, and Quebec (see Rivers, 1997; Whitmeyer & Karlstrom, 2007). For example, Bradore Formation sandstone above the basement unconformity in the Bonne Bay area has a 1033 Ma age peak (sample 2019-12, fig. 4) that reflects derivation from the 1032 Ma Lomond River granite at the southern end of the Long Range Inlier (fig. 2), which elsewhere in the Great Northern Peninsula comprises ca. 1630–980 Ma igneous and metaigneous rocks (Heaman et al., 2002). Indian Head Range granitoids that similarly underlie Bradore Formation strata in SW Newfoundland yield zircon U-Pb ages of 1140–1135 Ma and have 1540–1240 Ma inheritance (Hodgin et al., 2021). Blow Me Down Brook and Summerside Formation rocks locally contain potassium feldspar, muscovite, and garnet grains along with 1030–1012 Ma detrital zircon age peaks and 1650–970 Ma age fractions and therefore also demonstrate that Humber Arm allochthon strata had local sources from the eastern Grenville Province. Early Tonian (ca. 950 Ma) age fractions may indicate volcanic rock sources in the Baie Verte Peninsula (Strowbridge et al., 2022), but otherwise correspond with post-Grenvillian magmatism in southern Labrador (ca. 955 Ma: Heaman et al., 2002). Mid-Tonian (ca. 920–830 Ma) detrital zircon grains are minor constituents in our samples and may be ultimately sourced from ca. 920–840 Ma mafic to felsic intrusive rocks in Scotland and Ireland or recycled through upper Neoproterozoic strata in NE Laurentia (e.g., Cawood, Nemchin, Strachan, et al., 2007; Olierook et al., 2020). These ca. 920-840 Ma igneous rocks were located near SE Greenland prior to the opening of the North Atlantic Ocean and generally indicate south to southwest-directed transport of Tonian detrital zircon grains during Neoproterozoic to early Cambrian time.

Paleoproterozoic detrital zircon ages comprise 0–33% of our samples (17% of dataset) and are interpreted to have provenance from igneous rocks associated with the Trans-Hudson, New Quebec, Torngat, and other orogens that record the ca. 2000–1800 Ma collision of Archean cratons (fig. 6, e.g., Hoffman, 1988; Whitmeyer & Karlstrom, 2007). For example, several of our samples yield ca. 1900–1800 Ma age peaks that correspond to Aillik Group felsic volcanic rocks and Island Harbour Bay granitoids of the Makkovik Province in SE Labrador (e.g., LaFlamme et al., 2013). The subchondritic to superchondritic Hf isotope compositions of Stenian to Calymmian detrital zircon grains indicate contributions from depleted mantle and reworked Paleoproterozoic crust (e.g., Olierook et al., 2020), whereas Statherian to Orosirian detrital zircon grains have more negative εHf(t) excursions and indicate reworking of Archean crust (e.g., LaFlamme et al., 2013). Paleoproterozoic detrital zircon grains are likely polycyclic and recycled through post-Grenville strata during the multi-stage breakup of Rodinia (e.g., Cawood, Nemchin, Strachan, et al., 2007).

Archean detrital zircon ages make up 0–30% of our samples (17% of dataset) and demonstrate provenance from the Superior and North Atlantic cratons in eastern Canada and southern Greenland, respectively (fig. 6, e.g., Hoffman, 1988). The most proximal sources of Neoarchean to Mesoarchean detrital zircon age fractions in our samples, which result in ca. 2800–2700 Ma age peaks, may be derived from metaigneous rocks in the Nain Province or North Atlantic craton of Labrador (e.g., Dunkley et al., 2020) that yield subchondritic to superchondritic Hf isotope compositions (e.g., Wasilewski et al., 2021) like those documented in Labrador and Curling group strata. The U-Pb ages and subchondritic to chondritic Hf isotope compositions of Paleo- to Eoarchean (ca. 3300–3800 Ma) detrital zircon grains in the Hawke Bay and Irishtown formations overlap with those from North Atlantic craton gneiss units in Labrador (Wasilewski et al., 2021) and SW Greenland (Kemp et al., 2019). Archean detrital zircon grains in our samples were likely recycled through Proterozoic strata that have provenance from underlying crystalline basement or sedimentary sequences in the Grenville foreland (e.g., Cawood, Nemchin, Strachan, et al., 2007).

5.3. Testing stratigraphic correlations with detrital zircon statistical assessments

Fossil and other geological constraints have been used to argue stratigraphic continuity between Labrador Group, Curling Group, and Fleur de Lys Supergroup rocks in western Newfoundland, and, more broadly, connections with the Neoproterozoic to lower Paleozoic platform-slope system of eastern Laurentia (fig. 3, e.g., James et al., 1989; Lavoie et al., 2003). Taconic and younger deformation events have disrupted original depositional relationships and therefore our new detrital zircon results provide an opportunity to examine proposed Ediacaran to Cambrian stratigraphic correlations with statistical assessments (Kolmogorov-Smirnov, Kuiper, Cross-correlation, Similarity, and Likeness test results in table S3). Herein we use the Kolmogorov-Smirnov (K-S) D statistic and multi-dimensional scaling (MDS) to interpret stratigraphic connections. Although K-S dissimilarities are sensitive to sample size, corresponding MDS plots provide sensible configurations because most detrital studies rely on the relative differences between age distributions (Vermeesch, 2018). Other detrital zircon studies have effectively used the K-S test D statistic to resolve provenance connections for datasets with sample size differences (Beranek et al., 2023; McClelland et al., 2021, p. 2023). The K-S test D statistic is most sensitive about the median of the age distribution, which is preferred here so that small populations do not significantly influence pairwise comparisons (Sundell & Saylor, 2017; Wissink et al., 2018).

5.3.1. Correlations between lower Labrador and lower Curling Group strata

Pairwise comparisons of two Bradore Formation samples (MS2019-08, MS2019-12) yield U-Pb and U-Pb-Hf isotope K-S test D statistic values of 0.44 and 0.19, respectively (perfect overlap between two cumulative distribution functions would return D values = 0, no overlap would return D values = 1; Vermeesch, 2018). The U-Pb D statistic value of 0.44 results from our samples having distinct unimodal Mesoproterozoic age peaks that reflect differences in the crystallization ages of underlying basement rocks, whereas the U-Pb-Hf isotope D statistic value of 0.19 indicates less dissimilarity because both sandstone units were mostly derived from similar Neoproterozoic to Mesoproterozoic crustal units of the eastern Grenville orogen. The Bradore Formation samples are correspondingly far apart in the U-Pb MDS plot (fig. 7A), but close neighbors in the U-Pb-Hf isotope MDS plot (fig. 7B). Bradore Formation strata filled local basins (Bostock et al., 1983), and therefore the two samples could be time-equivalent, but not have stratigraphic continuity.

Pairwise comparisons of two Summerside Formation turbiditic sandstones (MS2019-05, MS2019-06) yield U-Pb and U-Pb-Hf isotope K-S test D statistic values of 0.10 and 0.13, respectively. These results support the hypothesis that turbidity current processes result in well-mixed deposits (DeGraaff-Surpless et al., 2003) which are not statistically different in detrital zircon U-Pb-Hf isotope space (figs. 7A, 7B). Pairwise comparisons of three Blow Me Down Brook Formation debris flow sandstones (MS2019-04, MS2019-15, 30LB16) yield slightly greater U-Pb and U-Pb-Hf isotope K-S test D statistic values of 0.12 to 0.23 and 0.11 to 0.33, respectively (figs. 7A, 7B). Stratigraphic correlations proposed for the Summerside and Blow Me Down Brook formations (fig. 3, Lavoie et al., 2003 and references therein) are supported by the low (0.10 to 0.20) U-Pb K-S test D statistic values and grouping of the five samples in figure 7A. We interpret that the greater U-Pb-Hf isotope K-S test D statistic values (0.18 to 0.31) between the five samples and distinct sample-grouping in figure 7B results from the poorly mixed nature of Blow Me Down Brook Formation debris flow strata. If the proposed stratigraphic correlations between lower Curling Group strata are correct, the Blow Me Down Brook and Summerside formations were sourced from basement-involved fault scarps or resulted from sediment bypass that delivered variably mixed sediment to the distal parts of the Humber margin. Proposed stratigraphic correlations between the Blow Me Down Brook, Summerside, and Bradore formations (Lavoie et al., 2003) are not evident from our U-Pb and U-Pb-Hf isotope K-S test D statistic values of 0.45 to 0.65 and 0.47 to 0.62, respectively, and corresponding distances shown in figures 7A and 7B. However, based our interpretations for the Bradore Formation herein, the results do not preclude time equivalence between basal units of the Labrador and Curling groups in SW Newfoundland.

5.3.2. Correlations between upper Labrador and upper Curling Group strata

Pairwise comparisons between two Hawke Bay Formation shoreface sandstones (31LB16, MS2019-10) yield U-Pb and U-Pb-Hf isotope K-S test D statistic values of 0.18 and 0.12, respectively, and correspondingly have close proximity to each other in figures 7A and 7B. Pairwise comparisons between these Hawke Bay Formation samples and an Irishtown Formation turbiditic sandstone (MS2019-01) similarly yield low U-Pb and U-Pb-Hf isotope K-S test D statistic values of 0.08 and 0.15 to 0.17, respectively (figs. 7A, 7B). An Irishtown Formation sandstone (MS2019-14) that is part of a debris flow succession likewise yields low U-Pb and U-Pb-Hf isotope K-S test D statistic values of 0.16 and 0.19 and 0.09 and 0.18, respectively, when compared with the two Hawke Bay Formation samples. Together these data provide statistical evidence that supports the proposed stratigraphic correlations (e.g., Lavoie et al., 2003) between quartz-rich strata of the upper Labrador and Curling groups. It is also notable that this debris flow sample (MS2019-14) has proximity and close-neighbor relationships with other Curling Group units in U-Pb and U-Pb-Hf isotope space (figs. 7A, 7B), which is consistent with predicted correlations or interfingering (e.g., Lavoie et al., 2003) between parts of the Blow Me Down Brook, Summerside, and Irishtown formations.

5.3.3. Correlations with Fleur de Lys Supergroup strata

The Flat Point Formation psammite of van Staal et al. (2013) that overlies ca. 564–556 Ma rocks of the Birchy complex plots near MS2019-05 and MS2019-06 in U-Pb space and correspondingly yields U-Pb K-S test D statistic values of 0.13 and 0.14 when compared to the Summerside Formation samples, whereas the Fleur de Lys Supergroup mica schist of Willner et al. (2014) has apparent statistical ties with our Bradore Formation samples in U-Pb space (fig. 7A). A boulder of Fleur de Lys Supergroup sandstone in an Ordovician conglomerate (Willner et al., 2014) similarly has proximity to our Summerside Formation samples in U-Pb space and yields U-Pb K-S test D statistic values of 0.16 and 0.20 when compared to MS2019-05 and MS2019-06 (fig. 7A). However, this sandstone boulder sample plots in U-Pb-Hf isotope space near MS2019-04 of the Blow Me Down Brook Formation (D statistic value of 0.24) and is more distanced from our samples of the Summerside and Bradore formations in figure 7B. Our working hypothesis is that these Fleur de Lys Supergroup rocks were correlative with parts of the lower Curling Group, including Summerside and Blow Me Down Brook strata known or inferred to overlie rift-related volcanic rocks and Grenville Province crust (e.g., Cawood & van Gool, 1998; Williams & Cawood, 1989). For example, Blow Me Down Brook Formation strata that overlie pillowed and massive lavas in the Bay of Islands may be correlative with Flat Point Formation units that cover the Birchy complex in the Baie Verte Peninsula.

6. DISCUSSION

6.1. Late Ediacaran to early Cambrian establishment of the eastern Laurentian margin

The tectonic setting and paleogeographic significance of Humber margin strata have long been debated in the literature, which has fueled controversies for the Ediacaran to Cambrian evolution of eastern Laurentia. Most studies interpret the Humber margin in Newfoundland to have faced the Humber Seaway and outboard Dashwoods microcontinent, and not the Iapetus Ocean, but the details of these published scenarios vary (e.g., Cawood et al., 2001; Hodgin et al., 2022; Macdonald et al., 2014; Robert et al., 2021; Waldron & van Staal, 2001). For example, the two-phase rift model of Cawood et al. (2001) called for coeval, early Cambrian seafloor spreading in both the Humber Seaway and Iapetus Ocean, whereas Robert et al. (2021) favoured a single mid-ocean ridge system in west Iapetus between Dashwoods and outboard Western Sierras Pampeanas and/or Arequipa-Pampia-Antofalla terranes. van Staal et al. (2013), Chew and van Staal (2014), and van Staal and Dewey (2023) used the available data to propose a magma-poor rift setting for the eastern Laurentian margin system in Scotland, Ireland, Atlantic Canada, and eastern United States, and specifically predicted that Birchy complex rocks in western Newfoundland comprise parts of an ancient ocean-continent transition zone akin to those documented along the west Iberian margin and in the Alps. The Humber margin in this magma-poor rift scenario was established after hyperextension along the west side of the Dashwoods microcontinent, which was interpreted by van Staal et al. (2013) to have initiated as a hanging-wall block (or H-block, see Péron-Pinvidic & Manatschal, 2010), and bounded by detachment faults which exhumed continental mantle to the surface. Humber margin strata in the model of van Staal et al. (2013) were deposited following the Cambrian Series 2 onset of thermal subsidence, ~20–30 Myr after hyperextension and the late Ediacaran rift-related magmatism in the Canadian Appalachians. An unexplored element of van Staal et al. (2013)’s hypothesis is that some magma-poor margins are established by a two-step process with crustal breakup before mantle breakup (e.g., Huismans & Beaumont, 2011, 2014) and stratigraphic studies have accordingly recognized crustal and mantle breakup sequences in basins that record the transition between the timing of rupture and onset of thermal subsidence (Alves & Cunha, 2018; Chao et al., 2023; Soares et al., 2012, 2014). In combination with the new depositional age, sediment provenance, and stratigraphic interpretations reported herein, we use modern magma-poor rift analogues to propose that the Labrador and Curling groups comprise parts of crustal and mantle breakup sequences deposited along eastern Laurentia.

6.1.1. Late Ediacaran crustal breakup in western Newfoundland

The crustal breakup phase in the Newfoundland (SE Grand Banks)-west Iberia magma-poor rift system, which we use as a modern analogue for late Ediacaran to early Cambrian evolution of the Humber margin (fig. 8A), was characterized by hyperextension or extreme thinning of the crust to <10 km (e.g., thinning and exhumation phases of Peron-Pinvidic et al., 2013; Péron-Pinvidic & Manatschal, 2010) and bimodal magmatism along inherited, basement-involved faults in onshore (Peace et al., 2024) and offshore Newfoundland (Beranek et al., 2022; Hutter & Beranek, 2020; Johns-Buss et al., 2023) and onshore (Mata et al., 2015) and offshore Portugal (Pereira et al., 2017). Major faults at this stage of rift evolution were localized along the edges of H-blocks and penetrated the mantle lithosphere (e.g., decoupled deformation of Sutra et al., 2013), eventually resulting in the exhumation of lower crust and mantle rocks. The tectonic erosion of H-blocks during the exhumation phase locally generated extensional allochthons, which are unrooted, thin (<5 km-thick) crustal slices underlain by major detachment systems in outboard areas floored by exhumed mantle (Péron-Pinvidic & Manatschal, 2010). Crustal breakup sequences span ~20 Myr in the Newfoundland-west Iberia rift system and are mostly recognized by fluvial-deltaic strata that were deposited during a forced regression in terrestrial and shallow-marine settings (fig. 8B), whereas correlative deep-water breakup sequences contain debris flow and turbiditic strata delivered to continental slope environments by sediment bypass processes (Alves & Cunha, 2018).

We propose that late rift and crustal breakup processes in the Newfoundland sector of the eastern Laurentian rift system occurred between 570–550 Ma and resulted from hyperextension and crustal necking processes (fig. 8A, cf., Chew & van Staal, 2014; van Staal et al., 2013) best documented by Birchy complex and related ocean-continent transition zone rock units in the Baie Verte Peninsula. The tectonic erosion of Laurentian crust and development of an extensional allochthon in the Baie Verte area (Rattling Brook block of van Staal et al., 2013), which is basement to some Fleur de Lys Supergroup strata, is also consistent with late Ediacaran thinning and exhumation during crustal breakup. Bimodal magmatism coincident with late Ediacaran crustal breakup processes, like that observed in the modern Newfoundland-west Iberia system, was focused near basement-involved transfer or transform faults. Isostatic adjustment may have been a driving force for partial melting of subcontinental mantle rocks along these faults during crustal breakup. For example, igneous rocks assigned to the ca. 551 Ma Skinner Cove Formation and ca. 555 Ma Lady Slipper pluton are exposed along the Serpentine Lake and Bonne Bay transform faults (figs. 1B, 2B). Tibbit Hill Formation volcanic rocks, Lac Matapédia volcanic rocks, and Sept Îles complex rocks in mainland Atlantic Canada were also emplaced during the 570–550 Ma interval along the Missisquoi, Saguenay-Montmorency, and Sept Îles transforms (fig. 1B), respectively. The stratigraphic components, thicknesses, and exact locations of the late Ediacaran crustal breakup sequences are not well constrained, but based on Newfoundland-west Iberia modern analogues it is feasible that basal, unfossiliferous strata assigned to the Bradore Formation in the Bonne Bay and Indian Head Range areas are late Ediacaran and deposited during a forced regression (fig. 8C). Potentially time-equivalent rocks of the lowermost Blow Me Down Brook Formation that overlie and are interbedded with Ediacaran mafic volcanic units (Gillis & Burden, 2006; S. E. Palmer et al., 2001; Waldron et al., 2003) are also crustal breakup sequence candidates and deposited by sediment bypass processes in deep water settings (fig. 8D). Although speculative, we predict that Summerside Formation turbiditic strata are parts of a crustal breakup sequence based on detrital zircon statistical correlations with Flat Point Formation rocks that cover the Birchy complex (fig. 8D). The base of the Summerside Formation is not exposed and its depositional relationships with underlying crystalline basement, Ediacaran volcanic rocks, or other units are uncertain. We call for future studies to precisely date the eruption ages of Ediacaran volcanic rocks in the Humber Arm allochthon and conduct new mapping and physical stratigraphic studies of interbedded and overlying Curling group rocks to test our hypotheses and characterize the map extent and development of this crustal breakup sequence.

6.1.2. Late Ediacaran to early Cambrian mantle breakup in western Newfoundland

The mantle breakup to passive margin phase in the Newfoundland-west Iberia rift system, which we use as a modern analogue for the early Cambrian evolution of the Humber margin (fig. 8E), was characterized by excess magmatism in outboard regions underlain by exhumed mantle and hyperextended crust (e.g., Bronner et al., 2011; Eddy et al., 2017), isostatic adjustment during stress release (e.g., Braun & Beaumont, 1989), and breakup-related deposition that included regressive-transgressive cycles linked to regional uplift and relative sea level fall. Lithospheric breakup in the Newfoundland-west Iberia rift system occurred ~20 Myr after first mantle exhumation, which implies that full continental rupture is unrelated to the thinning and exhumation phases of rift development (Péron-Pinvidic & Manatschal, 2010). Soares et al. (2012) showed that the mantle breakup sequence of western Portugal has four units which from oldest to youngest represent a forced regressive systems tract, transgressive systems tract, highstand systems tract, and transgressive systems tract with aggradational patterns at the base that transition upwards into carbonate-rich passive margin deposits (fig. 8F). An unconformity or lithospheric breakup surface is located at the base of the forced regressive interval in the inner proximal region underlain by thick crust (fig. 8F), but more distal regions of the Newfoundland margin show conformable contacts or diastems with strata related to mass wasting and sediment bypass (fig. 8G, Alves & Cunha, 2018; Soares et al., 2012).

We propose that the mantle breakup to passive margin phase in western Newfoundland resulted from complete lithospheric rupture between eastern Laurentia and Dashwoods. The precise timing of mantle breakup is uncertain, but it initiated after ca. 570–550 Ma exhumation of the Birchy complex. Lithospheric breakup in the modern Newfoundland-west Iberia rift system was diachronous and propagated from south to north, perhaps because of northward decrease in magma budget (Bronner et al., 2011); it is possible that lithospheric breakup in the eastern Laurentian rift system was also time-transgressive. Using the mantle breakup framework of Soares et al. (2012) and Alves and Cunha (2018), in combination with the established sequence stratigraphy of fossil-bearing units in the Labrador Group (e.g., Knight, 2013; Skovsted et al., 2017), we propose that: (1) lower to upper Bradore Formation strata are parts of a forced-regressive systems tract and the result of isostatic adjustment after mantle breakup; (2) upper Bradore Formation and lower Forteau Formation marginal-marine to marine strata preserve a transgressive systems tract capped by a maximum flooding surface; and (3) upper Forteau Formation and Hawke Bay Formation strata comprise a highstand systems tract capped by a sequence boundary and overlain by Miaolingian and younger passive margin rocks of the Port au Port Group (fig. 8H). A comparable stratigraphic evolution is inferred for lower Cambrian rock units of the Humber Arm allochthon, including: (1) turbiditic to debris flow deposits that comprise most of the Summerside and Blow Me Down Brook formations; and (2) Irishtown Formation turbiditic strata that are capped by a sequence boundary and overlain by passive margin rocks of the Northern Head Group (fig. 8I).

6.2. Correlations with Laurentian rift systems along the southern Caledonian-northern Appalachian orogenic belt and targets for future research

Crustal and mantle breakup events proposed in western Newfoundland were part of a continuum of Neoproterozoic to early Paleozoic rift processes that terminated with the establishment of the eastern Laurentian margin. Here we build on hypotheses for ancient magma-poor rift segments in the southern Caledonides and northern Appalachians to explore the tectonic significance of Ediacaran to Cambrian strata in eastern Laurentia and consider targets for future research.

6.2.1. Scotland and Ireland

Metasedimentary and metaigneous rocks of the Argyll and Southern Highland groups and their equivalents comprise the upper parts of the Dalradian Supergroup and record the Ediacaran to early Cambrian tectonic evolution of the Scotland and Ireland sectors of eastern Laurentia (e.g., Prave et al., 2023; Strachan & Holdsworth, 2000). The plate tectonic setting and depositional ages of these rocks are generally constrained by: (1) 604 ± 7 Ma and 612 ± 19 Ma syn-depositional barite deposits associated with upper Argyll Group mafic volcanic rocks (Easdale subgroup, Moles & Selby, 2023); (2) 595 ± 4 Ma (Halliday et al., 1989) and 601 ± 4 Ma (Dempster et al., 2002) zircon U-Pb ages for intrusive and tuffaceous units in the upper Argyll Group, respectively (e.g., Tayvallich volcanics); (3) correlation between some upper Argyll Group rocks and ca. 580 Ma Gaskiers diamictites (e.g., Prave et al., 2009); (4) ca. 576 Ma detrital zircon grains in Southern Highland Group equivalents that were derived from underlying rift-related volcanic rocks (Asta spilites; Strachan et al., 2013); and (5) Cambrian Series 2 siliciclastic and carbonate rocks of the uppermost Southern Highland Group and their equivalents that yield Tonian to Mesoarchean detrital zircon grains consistent with provenance from crystalline basement units in Labrador and Greenland (Cawood et al., 2003; Cawood, Nemchin, & Strachan, 2007; Cawood, Nemchin, Strachan, et al., 2007; Strachan et al., 2013).

Chew (2001) and Chew and van Staal (2014) concluded that upper Dalradian Supergroup successions contain ocean-continent transition zone rocks, including serpentinized continental mantle blocks and syn-sedimentary melange, which developed during regional hyperextension. For example, the Ben Lui schist unit in the Argyll Group of Scotland contains detrital chromite, chromian magnetite, and fuchsite grains and serpentinite olistoliths sourced from exhumed mantle rocks (Chew, 2001). Ultramafic detritus and serpentinite olistoliths are also embedded in graphitic pelites and spatially associated with mafic volcanic rocks of the Easdale subgroup (Chew, 2001) that are potentially correlative with ca. 612–600 Ma units in Scotland (Moles & Selby, 2023). Chew and van Staal (2014) proposed that these ocean-continent transition zone rocks were generated in a setting analogous to those of the Birchy complex in western Newfoundland, which based on our tectonic model herein, calls for the Ben Lui schist and related mafic volcanic rocks in the Argyll Group (Easdale and Tayvallich subgroups) to indicate the onset of crustal breakup by 610-600 Ma and deposition of a crustal breakup sequence in the Irish and British Isles (fig. 9A). Hyperextension and crustal breakup may have been connected to the outboard development of a Laurentian-affinity H-block (e.g., Tyrone Central Inlier in Ireland, Chew & van Staal, 2014). Although speculative, we propose that a later volcanic event, identified by ca. 576 Ma detrital zircon grains and mafic lavas in the upper Southern Highland Group and equivalents (Loch Avich Lavas Formation, Fettes et al., 2011; Asta spilites, Strachan et al., 2013), approximate the onset of mantle breakup (fig. 9A). In this scenario, full lithospheric rupture was magma-assisted and occurred ~20 Myr after first mantle exhumation, like that proposed for the modern Newfoundland-Iberia rift system. It follows that Ediacaran to Cambrian Series 2 strata of the upper Southern Highland Group and its equivalents comprise a mantle breakup sequence (fig. 9A). We predict that the oldest parts of the Scotland-Ireland mantle breakup sequence were deposited during late Ediacaran crustal breakup processes in western Newfoundland (fig. 9B), which implies southward propagation of the eastern Laurentian rift system.

Future studies that constrain the depositional age, high-n detrital zircon provenance, and regressive-transgressive depositional cyclicity of upper Dalradian Supergroup strata are warranted to test our hypotheses. Potential candidates within the proposed mantle breakup sequence in Scotland include the Ardveck Group (upper Southern Highland Group equivalents) that were predicted by Cawood, Nemchin, & Strachan, 2007 to be correlative with the Bradore, Forteau, and Hawke Bay formations in western Newfoundland (figs. 9A, 9B). Ardveck Group strata sit unconformably on Precambrian rocks and are overlain by carbonate units of the Durness Group that are equivalent to passive margin units of the Port au Port Group (fig. 9A, Cawood, Nemchin, & Strachan, 2007).

6.2.2. Northeastern United States and southeastern Canada

The eastern Laurentian rift system in the Quebec, Vermont, and Massachusetts Appalachians includes metasedimentary and metaigneous rocks that are exposed within structural inliers and windows. Eastern Laurentian rift evolution in these autochthonous and allochthonous successions is generally defined by: (1) ca. 570–555 Ma bimodal volcanic rocks (e.g., Tibbit Hill and Pinney Hollow formations; Hodych & Cox, 2007; Kumarapeli et al., 1989); (2) upper Ediacaran to Cambrian Series 2 sandstone, conglomerate, and shale units that overlie or are interlayered with volcanic rocks and locally overlie Grenville Province crystalline basement (e.g., Shickshock, St-Roch, Caldwell, and Oak Hill groups and Hoosac, Dalton, and Pinnacle formations; Allen et al., 2010; Landing, 2012; Pinet et al., 1996); and (3) Cambrian Series 2 and younger carbonate and siliciclastic rocks that indicate a transition to passive margin deposition (e.g., Forestdale and Cheshire formations; e.g., Landing, 2012; Macdonald et al., 2014).

Allochthonous Laurentian margin successions, including metasedimentary units assigned to the Rowe belt in New England and Pennington Sheet in Quebec, contain lenses of ultramafic rocks interpreted as segments of an ocean-continent transition zone (Chew & van Staal, 2014; Macdonald et al., 2014). Ultramafic lenses in the Rowe belt are exposed within metasedimentary units correlative with the ca. 571 Ma Pinney Hollow Formation, which indicates late Ediacaran mantle exhumation processes in New England were broadly equivalent to those in Newfoundland (fig. 9C, e.g., Karabinos et al., 2017; Macdonald et al., 2014). We interpret the available data to indicate that ca. 570–555 Ma igneous rocks and ultramafic-bearing metasedimentary successions in this region were generated during crustal breakup and hyperextension. As with the tectonic models for Scotland-Ireland and Newfoundland proposed herein, late Ediacaran crustal breakup in southern Quebec, Vermont, and Massachusetts may have been linked with the rifting of a Laurentian-affinity H-block (Rowe block or Chain Lakes block; Karabinos et al., 2017; Macdonald et al., 2014). The crustal breakup sequence would include Pinnacle, Pinney Hollow, and ultramafic-bearing Rowe belt units in New England and equivalent units in Quebec that are interbedded and overlie Ediacaran volcanic rocks (fig. 9C); such units could be the targets of future bedrock mapping and multi-proxy sediment provenance studies that aim to precisely constrain the chronology of crustal breakup. The age of mantle breakup is uncertain, but recycled 536 ± 27, 537 ± 21, and 540 ± 24 Ma detrital zircon grains in lower Paleozoic strata of the Laurentian autochthon and Taconic allochthons in New England (all ages reported at 2 Macdonald et al., 2014) may constrain the timing of late Ediacaran to early Cambrian magma-assisted lithospheric rupture that occurred ~10–30 Myr after hyperextension and mantle exhumation (fig. 9C). Based on established stratigraphic correlations along the eastern Laurentian margin (e.g., Landing, 2012; Lavoie et al., 2003), we predict that lower Cambrian rocks that record the transition to passive margin deposition in Quebec (e.g., Oak Hill Group strata) and New England (e.g., Dalton, Cheshire, and other formations) comprise mantle breakup sequences and contain regressive-transgressive depositional cycles comparable to those for the Bradore, Forteau, and Hawke Bay formations in western Newfoundland (fig. 9C).

7. CONCLUSIONS

Labrador and Curling group strata in western Newfoundland constrain the establishment of the Humber passive margin along eastern Laurentia. Upper Ediacaran to Cambrian Series 2 sandstone units of the lower Labrador and Curling groups, including terrestrial to deep-marine strata that overlie crystalline rocks and rift-related lavas, have immature detrital mineral constituents (e.g., feldspar, muscovite, garnet) and ca. 1000–1500 Ma detrital zircon age fractions which indicate local provenance from eastern Grenville Province basement. Deep-marine units of the lowermost Curling Group are probably correlative with metasedimentary rocks (Fleur de Lys Supergroup) that overlie ultramafic units within an ocean-continent transition zone. Using modern analogues from the Newfoundland-west Iberian rift system in the North Atlantic Ocean, upper Ediacaran to Cambrian Series 2 strata comprise parts of a crustal breakup sequence that was deposited in response to 570–550 Ma hyperextension along the eastern Laurentian margin. Crustal breakup was associated with the development of major detachment faults at the edges of the Dashwoods H-block, which eventually resulted in the exhumation of continental mantle. Late Ediacaran to early Cambrian breakup of mantle lithosphere was associated with the separation of Dashwoods from eastern Laurentia and ultra-slow spreading in the Humber Seaway marginal ocean basin. Lithospheric rupture was followed by the deposition of a mantle breakup sequence, including Cambrian Series 2 to Miaolingian sandstones of the lower to upper Labrador and Curling groups, that yield 556–586 Ma and 1000–2700 Ma detrital zircon grains and indicate derivation from Proterozoic igneous and sedimentary rocks. The mantle breakup sequence from oldest to youngest comprises a Cambrian Series 2 forced-regressive systems tract, an overlying Cambrian Series 2 transgressive systems tract capped by a maximum flooding surface, and a Cambrian Series 2 to early Miaolingian highstand systems tract capped by a sequence boundary. Upper Cambrian to Lower Ordovician carbonate rocks that overlie the mantle breakup sequence constrain the establishment of the Humber passive margin in western Newfoundland. Analogous magma-poor rift processes and stratigraphic products are recognized in the Scotland-Ireland and SE Canada-NE United States segments of the eastern Laurentian margin system and may indicate southward-propagation and opening of the Humber Seaway during the late Ediacaran to early Cambrian.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Project funding was provided by a Petroleum Exploration and Enhancement Program grant from Nalcor Energy and the Government of Newfoundland & Labrador. John Hanchar and Core Research Equipment & Instrument Training Network staff members Wanda Aylward, Rebecca Lam, and Markus Wälle aided laboratory studies at Memorial University of Newfoundland. Jeffrey Pollock, Stephen Piercey, and David Lowe provided helpful feedback on the MSc thesis of Maya Soukup. Shawna White, an anonymous reviewer, Associate Editor Peter Cawood, and Editor Mark Brandon provided constructive comments that improved this manuscript.