1. INTRODUCTION

Interpretations of global carbon isotope (δ13C) excursions in shallow water (<200 m water depth) carbonate sediments and rocks inform models of global environmental change across Earth history, often over intervals of biotic turnover. Classically, these interpretations assume platform carbonate δ13C values approximate the δ13C composition of dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) within the global ocean (Kump & Arthur, 1999). This assumption is not testable prior to the proliferation of planktic calcifiers in the Mesozoic and consequent expansion of the carbonate archive beyond the continental shelf. However, in the Cenozoic, this assumption has been shown to sometimes be invalid. For example, records of δ13C values in shallow water carbonate sediments over the last 10 million years exhibit δ13C values that are several per mil more positive than the δ13C values from the open ocean over the same time interval (Swart, 2008; Swart & Eberli, 2005), providing empirical evidence that shallow water carbonate sediments across the globe can be systematically, synchronously decoupled from open-ocean inorganic carbon pools. Even during perturbations to the global carbon cycle caused by the addition of large amounts of carbon depleted in 13C (relative to atmospheric CO2), like that interpreted at the Paleocene–Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM), shallow marine carbonates preserve δ13C trends quantitatively distinct from those recorded in deep and surface ocean archives (Li et al., 2020, 2021).

Shallow water carbonate sediments form in environments that are not as well connected to the large reservoirs of inorganic carbon in the ocean-atmosphere system as deeper water carbonate facies. Compared to pelagic carbonates, δ13C values of shallow water carbonate sediments are characterized by a much larger range of values compared to pelagic carbonates, which are controlled by a wide range of carbonate sources (e.g., microbes, algae, invertebrates, abiogenic particles) and local processes (e.g., Geyman & Maloof, 2019). Local phenomena that affect the δ13C composition of shallow water carbonate sediment can have global drivers; for example, changes in eustatic sea-level, resulting in an expansion of platform areas, have been hypothesized to generate synchronous δ13C excursions in platform sediments during the late Ediacaran Period through enhanced productivity and/or evaporation in shallow marine environments (Busch et al., 2022). Additionally, studies of shallow water marine carbonate sediments indicate that early diagenetic alteration and associated changes in mineralogy can alter the chemical composition of the carbonate sedimentary archive after deposition (Fantle & Higgins, 2014; Higgins et al., 2018; Swart & Eberli, 2005). In particular, carbonate δ44/40Ca, δ26Mg, and Sr/Ca records have been shown to systematically covary during early diagenesis (Ahm et al., 2019; Blättler et al., 2015; Higgins et al., 2018) and have been used to identify local alteration of shallow marine carbonate δ13C records of ancient carbonate strata (e.g., Ahm et al., 2021; D. S. Jones et al., 2020). Thus, while global δ13C excursions preserved in shallow marine carbonate δ13C records can reflect global perturbations to the carbon cycle (e.g., during the PETM), they can also (or instead) record local forcings (which may, in some cases, respond to global sea level).

A global <−6‰ δ13C excursion is documented from shallow water carbonate δ13C records that span the Ediacaran–Cambrian (539–533 Ma) transition (e.g., Derry et al., 1992; Kaufman & Knoll, 1995; Magaritz et al., 1991; L. L. Nelson et al., 2023), a critical interval in the evolutionary history of life that saw turnover between early animal communities prior to the major radiation of motile and biomineralizing animals in the Cambrian Period. The excursion, termed the BAsal Cambrian carbon isotope Excursion (BACE) (Zhu et al., 2006), is considered to be broadly correlative among Ediacaran–Cambrian boundary sections because, in western Laurentia, it directly underlies the first occurrence of the ichnofossil Treptichnus pedum, the marker of the Cambrian Global Boundary Stratotype Section and Point (GSSP) (Brasier et al., 1994; Corsetti & Hagadorn, 2000; Narbonne et al., 1994). Interpreted as a record of global carbon cycle perturbation, the BACE has been used as evidence for environmental change immediately preceding the Cambrian Period with potential mechanistic links to end-Ediacaran biotic turnover (e.g., Amthor et al., 2003; Hodgin et al., 2021; Kimura et al., 1997; Kimura & Watanabe, 2001; Smith et al., 2023). It has also been used to identify the Ediacaran–Cambrian boundary where T. pedum does not appear due to taphonomic bias (e.g., Maloof et al., 2005; Zhou & Xiao, 2007), resulting in the development of regional and global chemostratigraphic age models for the Ediacaran–Cambrian transition (e.g., Bowyer et al., 2022; Maloof et al., 2010; L. L. Nelson et al., 2023; Smith et al., 2016).

However, there are reasons to suspect the BACE may not record a global carbon cycle perturbation. Due to the lack of a precise geochronological framework that calibrates the chemostratigraphic record across the Ediacaran–Cambrian boundary and the fact that there are several large negative carbon isotope excursions in the latest Ediacaran and earliest Cambrian, the BACE is not independently confirmed to be globally synchronous. This has manifested in several different stratigraphic age models for this interval of Earth history (e.g., Bowyer et al., 2022, 2024; L. L. Nelson et al., 2023). Additionally, it is difficult to explain the generation of global ocean DIC δ13C values <−6‰, especially for >105–106 years, based on modern steady-state carbon cycling. The δ13C composition of carbon entering the ocean reservoir is assumed to approximate mantle values of ~−6‰ (Kump & Arthur, 1999), which, over long time-scales, should equal the cumulative δ13C composition of carbon exiting the system via organic and inorganic carbon burial. However, this assumption of mantle value inputs does not always hold true. For example, in the Neogene, it has been shown that recycling of sedimentary kerogen and geogenic methane can drive the mean δ13C input to ~−8‰ (e.g., Derry, 2024). Photosynthesis fractionates carbon isotopes such that organic carbon is depleted in 13C relative to the mantle, requiring carbonate δ13C values to be greater than or, if no organic burial occurs, equal to mantle values. Shifts in carbon weathering inputs and in fractionation during photosynthesis can also impact δ13C records (Kump et al., 1999; Vogel, 1993), but neither of these have been proposed as viable drivers of a negative carbon isotope excursion of similar magnitude as the BACE. To generate a global carbonate δ13C excursion <−6‰, a large external pool of isotopically light carbon is needed; the δ13C composition of ocean DIC may reach values <−6‰ only if (1) a large amount of light carbon enters the ocean-atmosphere system or (2) a large amount of heavy carbon is removed from it. Because the BACE reaches below modern mantle δ13C values, models proposed to explain it as a record of global average DIC must invoke unconventional external carbon sources (e.g., Bjerrum & Canfield, 2011; Hodgin et al., 2021; Rothman et al., 2003; Svensen et al., 2004) or sinks (e.g., Laakso & Schrag, 2020).

Given these complications and those associated with interpreting the shallow water carbonate archive, it is reasonable to consider whether hypotheses that do not require a global carbon cycle perturbation can explain both the geochemical character and global nature of the BACE. Here, we revisit three carbonate-rich successions from the western margin of Laurentia, where the relationship between the BACE and the Ediacaran–Cambrian boundary was first established. We characterize the role of early diagenetic alteration in setting the chemical composition of carbonate sediments across the BACE using a suite of stable isotope (δ13C, δ18O, δ44/40Ca, δ26Mg) and trace elements (Sr/Ca) on carbonate records in concert with sedimentary observations. We find evidence that shallow water carbonate sedimentary strata recording the BACE are persistently influenced by early diagenetic alteration, yet based on geochemical fingerprints, the extent and nature of interpreted diagenetic regimes differ among the three study sites. Despite stratigraphic and lateral variability in the diagenetic alteration of preserved carbonates, the stratigraphic pattern of δ13C values across the BACE are consistent among the three sites. We discuss these results in the context of possible origins of the BACE and interpretations of carbon isotope excursions in shallow water carbonate sediments.

2. GEOLOGIC BACKGROUND

Ediacaran–Cambrian boundary strata of southwestern Laurentia record mixed siliciclastic-carbonate sedimentation during the protracted break-up of Rodinia (Armin & Mayer, 1983; Bond & Kominz, 1984; Fedo & Cooper, 2001; Karlstrom et al., 2020). These strata range from fluvio-marine deltaic to outer-shelf deposits, deepening to the west-northwest in present-day coordinates (Fedo & Cooper, 2001; C. A. Nelson, 1978; Smith et al., 2023; Stewart, 1970). The Ediacaran–Cambrian boundary, marked by the first occurrence of T. pedum, is recorded in correlative units from three regions: the Esmeralda Member of the Deep Spring Formation of the White and Inyo Ranges and Esmeralda County (CA and NV, USA), the lower member of the Wood Canyon Formation of the Death Valley region (CA and NV, USA), and the La Ciénega and overlying Cerro Rajón formations of the Caborca region (Mexico; fig. 1) (Corsetti & Hagadorn, 2003; Hagadorn & Waggoner, 2000; Loyd et al., 2012).

Litho- and sequence stratigraphy form the backbone for the correlation of Ediacaran–Cambrian strata from the southwestern United States (Stewart, 1970; Wheeler, 1948). Over the past several decades, bio- and chemostratigraphy have been used to substantiate, refine, and extend these correlations to outcrops near Caborca, Mexico (Corsetti & Hagadorn, 2000; Hodgin et al., 2021; Jensen et al., 2002; Loyd et al., 2012; Oliver & Rowland, 2002; Sour-Tovar et al., 2007; Stewart et al., 1984). Late Ediacaran body fossils are reported from Unit 1 of the La Ciénega Formation (Hodgin et al., 2021; Schiffbauer et al., 2024; Sour-Tovar et al., 2007; Stewart et al., 1984), the Dunfee Member of the Deep Spring Formation (Grant, 1990; Mount et al., 1983; Rivas et al., 2024; Selly et al., 2020; Signor et al., 1987; Smith et al., 2016, 2023; Taylor, 1966), and the first parasequence in the lower member of the Wood Canyon Formation (Evans et al., 2024; Hagadorn & Waggoner, 2000; Hall et al., 2020; Selly et al., 2020; Smith et al., 2017). Although moderately complex trace fossils have been found in upper Ediacaran strata at Mount Dunfee (Tarhan et al., 2020), the lowest occurrence of T. pedum is in the top ~75 m of the Esmeralda Member of the Deep Spring Formation (Corsetti & Hagadorn, 2003), at the base of the Cerro Rajón Formation (Barrón-Díaz et al., 2019; Hodgin et al., 2021; Loyd et al., 2012), and meters above the second dolostone interval of the lower Wood Canyon Formation (Corsetti & Hagadorn, 2000; Hagadorn & Waggoner, 2000).

The BACE is preserved across southwestern Laurentia, spanning sequence boundaries and variable carbonate facies, textures, and lithologies (Smith et al., 2023). It was first identified in southwestern Laurentia within the Dunfee and Esmeralda members of the Deep Spring Formation (Corsetti & Kaufman, 1994). There, a δ13C excursion with a nadir of −9.5‰ is preserved in limestone and dolostone strata (Corsetti & Kaufman, 1994; Smith et al., 2016, 2023; fig. 1B). A correlative δ13C excursion was later identified in the more proximal to paleo-shoreline Wood Canyon Formation, spread across the three dolostone units of the lower member (Corsetti & Hagadorn, 2000; fig. 1B). Although thick siliciclastic packages separate the dolostone units, obscuring the full expression of the BACE, a nadir of ~−9‰ is observed in the first dolostone unit (Corsetti & Hagadorn, 2000; Smith et al., 2023). In the lower member of the Wood Canyon Formation, a chemical abrasion isotope-dilution thermal ionization mass spectrometry (CA-ID-TIMS) U-Pb detrital zircon maximum depositional age of 532.83 ± 0.98 Ma coincides with the first positive δ13C excursion above the BACE (L. L. Nelson et al., 2023). Strata from the Wood Canyon and Deep Spring formations are also chemostratigraphically correlated with units 2 and 3 of the La Ciénega Formation, in which the BACE reaches δ13C values as low as −7.5‰ over ~50 m of dolostones and interbedded siliciclastic rocks (Hodgin et al., 2021; Loyd et al., 2012; fig. 1B). In the La Ciénega Formation, a CA-ID-TIMS U-Pb detrital zircon maximum depositional age of 539.40 ± 0.23 Ma was obtained from strata deposited ~20 m above the nadir of the BACE and ~10 m below the return to ~0‰ δ13C values (Hodgin et al., 2021). This maximum depositional age constrains the ascending limb of the BACE in Laurentia to ≤540 Ma. Previously, the southwestern Laurentian record of the BACE has been argued to be robust to alteration via meteoric diagenesis based on a lack of a clear relationship between δ18O and δ13C values of the BACE and the fact that the excursion stratigraphically spans multiple sequence boundaries and is laterally extensive over several hundreds of kilometers (L. L. Nelson et al., 2023; Smith et al., 2016, 2023).

3. MATERIALS AND METHODS

Samples were collected from three sites within the southwestern Great Basin (fig. 1A): Mount Dunfee, Nevada, USA (37.34162°, −117.31937°); Echo Canyon, California, USA (36.51906°, −116.66620°); and Cerro Rajón, Sonora, Mexico (30.41727°, −111.94530°). New geochemical data, including carbonate calcium isotope (‰, n=173) and magnesium isotope (‰, n=42) compositions and Mg/Ca (mmol/mol), Sr/Ca (mmol/mol), Mn/Ca (μmol/mol), U/Ca (μmol/mol) major and trace elemental ratios (n=186), are paired with previously published sedimentological observations, δ13C values, and δ18O values from the top 45 m of the Dunfee Member of the Deep Spring Formation and the entirety of the Esmeralda Member of the Deep Spring Formation at Mount Dunfee (Smith et al., 2016), the lower member of the Wood Canyon Formation at Echo Canyon (Smith et al., 2023), and the La Ciénega Formation at Cerro Rajón (Hodgin et al., 2021). All geochemical data were generated from the same carbonate powders, originally produced by Hodgin et al. (2021), Smith et al. (2016), and Smith et al. (2023) by micro-drilling cut carbonate samples, with care taken to avoid veins, fractures, and siliciclastic-rich laminae.

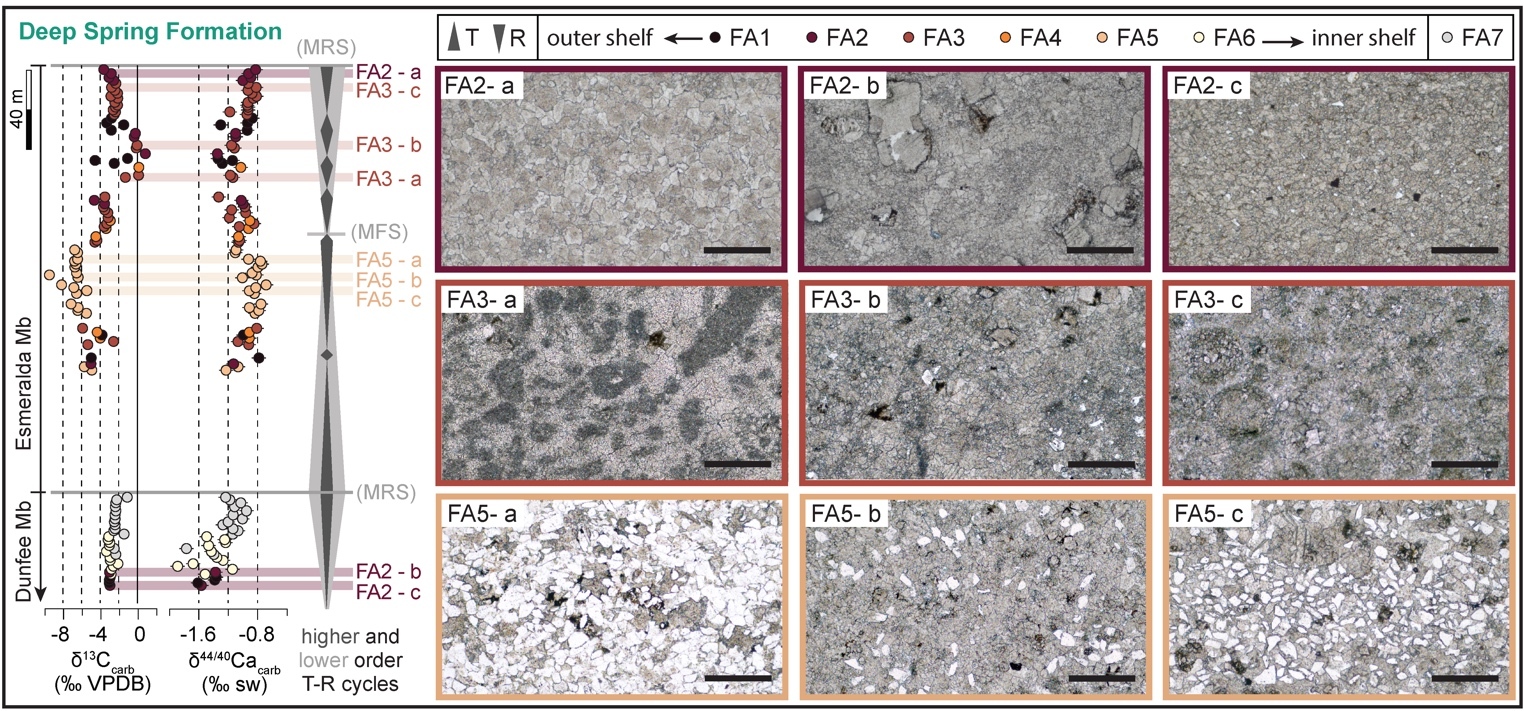

Facies associations are defined for the Esmeralda and upper Dunfee members of the Deep Spring Formation (after Wilson, 1974). They are based on field observations from Smith et al. (2016) and on new observations that were made as part of this study while retracing the stratigraphic section of Smith et al. (2016). High order transgressive-regressive cycles (after Catuneanu, 2017; Embry, 2002) were then identified in the Esmeralda Member, informed by stratigraphic changes in lithologies and carbonate facies. Additionally, twenty-three petrographic thin sections of carbonates from the Deep Spring Formation at Mount Dunfee were made from the samples that sourced powders. Samples were selected for thin-section based on their (1) calcium isotope composition and (2) facies assignment, with the goal of creating a sample set that reflected the variation in calcium isotope values and facies recorded throughout the stratigraphic section. Through petrographic observation of thin-sections, sample textures were characterized.

3.1. Trace and major element analyses

Following dissolution in buffered acetic acid (pH ~5) at Johns Hopkins University, samples were analyzed for elemental ratios at Princeton University using a Thermo Finnegan iCAP Q Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometer (ICP-MS), measured against a set of in-house (matrix-matched modern seawater and aragonite) and NIST standards (SRM88b). The external reproducibility of Sr/Ca and Mg/Ca are estimated from measurements of SRM88b to be <5% (2σ, n=16). The external reproducibilities of U/Ca and Mn/Ca ratios are estimated from measurements of SRM88b to be <12% and <3%, respectively (2σ, n=16).

3.2. δ44/40Ca and δ26Mg analyses

Samples were prepared and analyzed for calcium and magnesium isotope analyses at Princeton University. They were processed using an automated high-pressure ion chromatography (IC) system (Dionex ICS-5000+) and run on a Thermo Scientific Neptune Plus multi-collector ICP-MS following methods outlined in detail in Husson et al. (2015). The analyses were conducted in medium resolution mode, measuring 44Ca, 43Ca, and 42Ca using the sample-standard bracketing method. Calcium isotopic compositions are reported in delta notation as the relative abundances of 44Ca and 40Ca normalized against a modern seawater standard, assuming that the kinetic isotope mass fractionation law governs the relationship between δ44/40Ca and δ44/42Ca (e.g., Gussone et al., 2020). The external reproducibility of δ44/40Ca measurements of SRM915b is −1.18 ±0.17‰ (2σ, n=44). Magnesium isotopic compositions are reported in delta notation as the relative abundances of 26Mg and 24Mg normalized against Dead Sea Magnesium (DSM3). The external reproducibility of δ26Mg measurements of Cambridge-1 and modern seawater standards are −2.60 ±0.09‰ (2σ, n=8) and −0.82 ±0.10‰ (2σ, n=8), respectively.

4. RESULTS

4.1. The Deep Spring Formation at Mount Dunfee (Esmeralda County, NV)

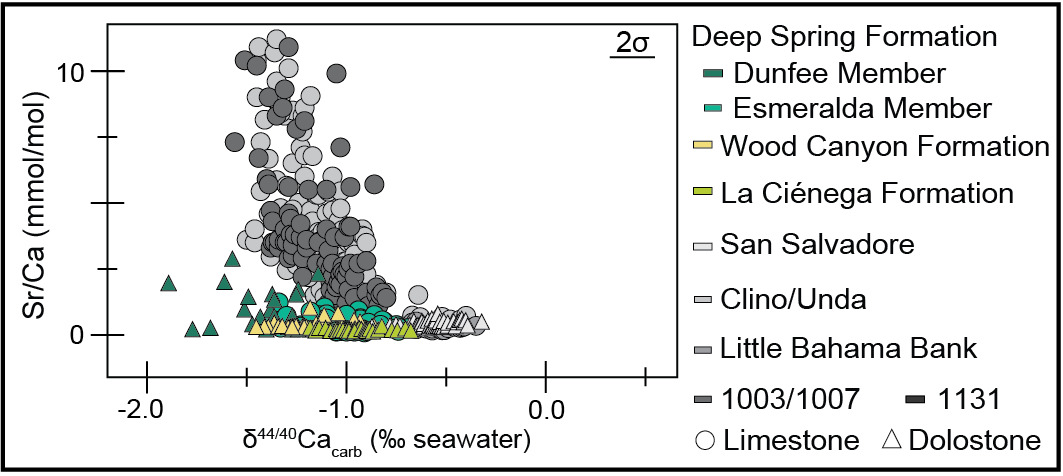

The measured section of the Deep Spring Formation at Mount Dunfee records stratigraphic variation in δ13C, δ18O, δ44/40Ca, and Sr/Ca values in both the Dunfee and Esmeralda members. In the uppermost 45 m of the Dunfee Member, there are interfingering limestone, dolomitic limestone, and dolostone intervals. Transitions from limestone to dolostone occur at ~20 m and ~40 m below the top of the member, but there is variability in these lithologies along strike (fig. 1B). These mineralogical shifts were observed in the field and confirmed using Mg/Ca mmol/mol ratios, with the cutoff between limestone to dolostone defined here at 600 mmol/mol. The transition to dolostone coincides with the stabilization of δ18O values averaging ~−15‰ (from values down to −25‰ recorded in the limestone), a shift in δ13C values from ~−3‰ to ~−2‰, and a decrease in Sr/Ca ratios (figs. 1B and 2). This transition towards the top of the Dunfee Member also coincides with a shift in δ44/40Ca values, in which dolostones in the upper 20 m of the member record δ44/40Ca values between −1.27‰ and −0.95‰, and the underlying limestones and dolostones record δ44/40Ca between −1.89‰ and −1.24‰. The Sr/Ca values of the limestone samples in the Dunfee Member are the highest of any of the samples measured but are low when compared to Sr/Ca values from the Bahamas platform (fig. 3).

In the limestone-dominated Esmeralda Member, δ44/40Ca values range from −1.3‰ to −0.7‰, while Sr/Ca ratios range from 0.1 mmol/mol to 1.2 mmol/mol. Stratigraphically, δ44/40Ca values show a systematic trend reaching highs (~0.8‰) at ~100 m and ~200 m above the base of the member (fig. 1B). Esmeralda limestones with high (≥−0.9‰) δ44/40Ca values have Sr/Ca ratios between 0.09 mmol/mol and 0.93 mmol/mol, while those with lower δ44/40Ca values have Sr/Ca ratios between 0.26 mmol/mol and 1.23 mmol/mol (fig. 2B). Relative to Sr/Ca values measured from sediment from sites on and around the Bahamas platform, all the values measured in this study, even those with more negative or sediment-buffered δ44/40Ca values, are relatively low (fig. 3). Covariation is also observed between δ44/40Ca, δ18O, and δ13C values in the Esmeralda Member. This covariation is most evident over the stratigraphic interval that records the ascending limb of the BACE, where δ44/40Ca vales decrease from ~−0.7 to −1.3‰, δ18O values increase from ~−18 to −9‰, and δ13C values increase from values as low as ~−9 to 1‰ (figs. 1B, 2A, and 4).

Of the three sections studied, the stratigraphic section of the Deep Spring Formation is the thickest and best texturally preserved. As such, it records the greatest diversity in carbonate facies. In the field, no macroscopic evidence of authigenic carbonate precipitation (e.g., calcite nodules, infilled void spaces) was observed. Seven carbonate facies associations were defined within this unit and paired with δ44/40Ca and δ13C data (FA1-FA7, table 1; fig. 5). FA1 and FA2 are interpreted to record outer shelf sedimentation just below and at fair-weather wave base, respectively. These facies are differentiated by the abundance of siltstone partings in FA1 and the preservation of low-angle cross-lamination in wackestones from FA2. FA3 consists of oolites, interpreted to record high-energy ooid shoals positioned on the outer to mid-shelf. Together, FA1, FA2, and FA3 comprise much of the Esmeralda Member. FA4 consists of stromatolites and limestone wackestone-grainstones, interpreted to record carbonate deposition in shelf environments shielded from high-energy conditions. The shallowest carbonate facies preserved in the Esmeralda Member are assigned to FA5, which consists of sandy limestone grainstone lenses among fine quartz-rich sandstones. FA5 is interpreted to record inner shelf sedimentation. Strata with FA5 facies assignment record the highest δ44/40Ca and lowest δ13C values (fig. 5). Strata belonging to FA6 and FA7 are reported only from the Dunfee Member. FA6 is defined by lime mudstone deposits with an abundance of micritic chip horizons, from which an inner shelf depositional environment is interpreted, while FA7 consists of fabric-destructive dolostones associated with a karstic dissolution surface, observed at the top of the Dunfee Member (fig. 1B).

In thin-section, the original depositional fabrics of carbonates are poorly preserved regardless of facies association, although relics of original structures remain in some samples (e.g., FA3-c in fig. 5). No correlation is observed between fabric retention and δ44/40Ca and δ13C trends recorded in limestone strata. For example, samples FA3-a and FA3-b record similar δ44/40Ca and δ13C values, but the fabric of FA3-b is more thoroughly replaced by neomorphic spar (fig. 5). Additionally, within FA5, the relative proportion of quartz grains does not clearly relate to δ44/40Ca and δ13C values; among the six FA5 samples observed in thin-section and 16 observed in hand sample, no trend was observed between quartz content and δ44/40Ca or δ13C values (fig. 5).

4.2. The Wood Canyon Formation at Echo Canyon (Death Valley region)

The samples from the lower Wood Canyon Formation at Echo Canyon are dolostone and record a shift in δ44/40Ca values from ~−1.4‰ to ~−1.0‰. This ~−0.4‰ shift is coincident with the downturn of the BACE and occurs in the basal 55 m of the section. Following an interval dominated by siliciclastic strata, carbonates re-appear at 158 m to 161 m, and 232 m to 240 m into the section, and record δ44/40Ca values between −0.9‰ and −1.2‰. The Sr/Ca ratios are consistently low, with values between 0.15 and 0.92 mmol/mol (figs. 1B and 2B).

4.3. The La Ciénega Formation at Cerro Rajón (Caborca region)

Carbonate strata from the section of the La Ciénega Formation at Cerro Rajón consist of dolostone with Sr/Ca ratios <0.3 mmol/mol (figs. 1B and 2B). These dolostones record δ44/40Ca values that oscillate between −0.7‰ and −1.2‰ over ~5 m to ~20 m-thick intervals. Strata that record the descending limb of the BACE record a ~−0.5‰ shift in δ44/40Ca values from −1.2‰ to 0.7‰, but δ44/40Ca and δ13C values generally do not covary in this section (figs. 1B and 2). The La Ciénega Formation also records stratigraphic fluctuation in δ26Mg values. Over the lower 122 m of the section, δ26Mg values oscillate between −2.7‰ and −1.7‰. Over the upper 20 m of the section, δ26Mg values decrease from −2.0‰ to −2.3‰. No consistent relationship is observed between δ44/40Ca and δ26Mg trends (fig. 1B). Metabasalt sills intrude carbonates that record the BACE at the Cerro Rajón site (Tapia-Trinidad et al., 2022), raising the potential for carbonate interaction with hydrothermal fluids during basalt emplacement.

5. DISCUSSION

5.1. Controls on δ44/40Ca trends in southwestern Laurentia

5.1.1. Influence of global calcium cycling

Stratigraphic trends in δ44/40Ca records across southwestern Laurentia are unlikely to be caused by temporal changes in the δ44/40Ca value of the ocean. Since the main calcium sink from the ocean is carbonate burial, bulk carbonate δ44/40Ca values cannot change over long timescales when the calcium cycle must be in steady state; or, put differently, the δ44/40Ca value of outputs must match those of the inputs for timescales >1 Myr (Gussone et al., 2020; Silva-Tamayo et al., 2018). Seawater δ44/40Ca values are also well-buffered against transient (<1 Myr) changes caused by temporary imbalances in calcium sources and sinks. This stability is controlled by carbonate compensation, in which changes in calcium input or outputs to the ocean are rapidly buffered by the carbonate saturation state For example, an increase in calcium sources would cause an increase in the saturation state, leading to precipitation of carbonate minerals. Modeling studies of the combined calcium and carbon cycles incorporating this effect have demonstrated that flux perturbations can only result in a maximum δ44/40Ca excursion of <0.3‰ (Komar & Zeebe, 2011, 2016).

Seawater δ44/40Ca values can only shift if there is a significant change in the fractionation between the bulk carbonate sink and seawater. For example, a shift in the dominant mode of carbonate precipitation from aragonite to calcite could cause a change in the δ44/40Ca value of seawater of <0.5‰. However, for this type of global perturbation to show up in the bulk carbonate record, it would have to occur rapidly, over <1 Myr time-scales, before the calcium cycle reaches a new steady-state. Previous calcium isotope studies of the Ediacaran–Cambrian transition show that this interval was dominated by primary aragonite precipitation and that this mode of carbonate precipitation persisted through most of the Cambrian before gradually transitioning to a calcite sea (Wei et al., 2022).

It is unknown how much time is captured by the strata from which we report δ44/40Ca variation. However, because δ44/40Ca values vary by ≥0.4‰ at all sites studied (figs. 1B and 2), the δ44/40Ca variation cannot be entirely attributed to perturbations to global calcium cycle. It instead must be controlled, at least in part, by local changes in primary carbonate mineralogy and/or carbonate recrystallization and neomorphism.

5.1.2. Influence of local controls on calcium isotope fractionation

The δ44/40Ca values presented here fall within the range of values predicted for either (1) a local change in conditions that control the dominant mineralogy of a platform during initial carbonate precipitation or (2) a transition between fluid-buffered and sediment-buffered conditions (with respect to calcium) during diagenesis (Ahm et al., 2018; Gussone et al., 2005). The relationship between Sr/Ca ratios and δ44/40Ca values observed from limestones from the Deep Spring Formation is consistent with either scenario (fig. 2B).

Mineralogy and precipitation rate are the primary controls on the Sr/Ca ratio and calcium isotope fractionation between CaCO3 and seawater, where aragonite (versus calcite) precipitation and high (versus low) precipitation rates are associated with greater depletion in 44Ca and higher Sr/Ca ratios (Fantle & DePaolo, 2007; Gussone et al., 2005; Tang et al., 2008). During neomorphism or recrystallization of carbonate minerals, precipitation rates do not appreciably fractionate calcium isotopes; however, during primary precipitation, they result in an ~−1.5‰ average offset between aragonite and seawater δ44/40Ca values and an ~−0.9‰ average offset between calcite and seawater δ44/40Ca values (Fantle & DePaolo, 2007; Gussone et al., 2005; Tang et al., 2008). One consequence of these fractionation effects is that fluid-buffered δ44/40Ca values are readily distinguishable from sediment-buffered δ44/40Ca values, with the more fluid-buffered values being closer to 0‰ and the more negative δ44/40Ca values representing sediment-buffered values. As the extent of alteration under fluid-buffered conditions increases, carbonate δ44/40Ca will approach fluid δ44/40Ca values — a record is “fully” fluid-buffered when carbonate values match fluid values. Fluid- and sediment-buffered conditions occur along a continuum, with no defined cutoffs between the two end members. Similarly, strontium partitioning during diagenesis versus primary precipitation results in diagenetic minerals (dolomite, low-Mg calcite) that are Sr-poor relative to precursor minerals (aragonite, high-Mg calcite) (Tang et al., 2008).

5.2. Influence of diagenesis on δ44/40Ca, δ18O, and δ26Mg records

The Dunfee Member of the Deep Spring Formation has the most negative δ44/40Ca values of any of the studied samples, recording evidence of the most sediment-buffered diagenetic conditions (figs. 1B and 2). Our findings are complementary with previous studies that have shown how both fluid- and sediment-buffered conditions can lead to the preservation of primary δ13C values depending on the depositional settings. Platform sediments that have been transported into deeper environments with little fluid flow (diffusion dominated), are argued to maintain their geochemical compositions in a sediment-buffered environment (Ahm et al., 2021; Husson et al., 2015). However, sediments deposited in shallow water environments can also preserve the δ13C values of platform DIC if they undergo early fluid-buffered marine diagenesis by seawater that is not significantly evolved from its original composition (Crockford et al., 2021). In the Deep Spring, lower Wood Canyon, and La Ciénega formations the range in δ44/40Ca values vary between the three sites (figs. 1B and 2). The δ44/40Ca values within the BACE specifically also vary, despite consistency in the shape and magnitude of the δ13C excursion. These variations in δ44/40Ca are interpreted to record fluctuating diagenetic conditions, with the more positive δ44/40Ca values recording more fluid-buffered diagenetic alteration. Of the three sections, the La Ciénega δ44/40Ca values are the most elevated (>~−1.2 ‰) indicative of persistent fluid-buffered alteration, consistent with the observed dolomitization of these strata (figs. 1B and 2). The range of δ44/40Ca values from the lower Wood Canyon and Deep Spring formations are more variable, showing both fluid- and more sediment-buffered intervals (fig. 2).

5.2.1. Early marine dolomitization

The dolostones of the La Ciénega and lower Wood Canyon formations record geochemical signatures indicative of early marine dolomitization. The preservation of high (>−0.8‰) δ44/40Ca values over some of the lower Wood Canyon Formation and throughout the La Ciénega Formation implies high degrees of alteration of δ44/40Ca values in reaction with seawater, analogous to that documented to occur during early marine dolomitization in the Bahamas (Higgins et al., 2018). Additionally, in each formation, dolostones record relatively stable δ18O values that are ~30‰ greater than Cambrian seawater δ18O estimates (~−36.3‰ relative to VPDB; Hearing et al., 2018), which is consistent with oxygen isotope fractionation between seawater and dolomite at temperatures <40°C (Horita, 2014; figs. 1B and 4A). Because δ18O records are sensitive to diagenetic overprinting, the preservation of a relatively low-temperature signal implies dolomitization occurred prior to deep burial.

The low δ26Mg values and high δ44/40Ca values of the La Ciénega Formation further support geochemical stabilization during early marine dolomitization. In dolostones, δ26Mg values can vary depending on magnesium availability during dolomitization. Generally, dolomites are depleted in 26Mg relative to the dolomitizing fluid due to magnesium isotope fractionation during dolomite formation (fractionation factor of ~2‰, Fantle & Higgins, 2014; Higgins & Schrag, 2010). In a Mg-poor system, however, dolomite can be variably enriched in 26Mg relative to a Mg-rich system due to Rayleigh-type distillation of the pore-fluid (Blättler et al., 2015). Over much of the La Ciénega Formation, δ26Mg values are low and scattered between −2.3 and −1.7‰. Moreover, a coupling of δ44/40Ca and δ26Mg values is observed in strata that record the BACE. There, δ26Mg values decrease by ~0.3‰ while δ44/40Ca values increase by ~0.4‰ (figs. 1B and 4B), suggesting a shift in local environmental conditions that favor more fluid-buffered diagenesis with respect to both elements (e.g., greater advective flux of dolomitizing fluids).

Several mechanisms have been modeled to drive early, extensive dolomitization of carbonate platforms (e.g., Kaufman & Knoll, 1995; Whitaker et al., 2004). Some of these have distinct predictions for the evolution of dolomitizing fluid chemistries and, consequently, carbonate geochemical records (e.g., Riechelmann et al., 2023). However, because initial platform geometries and paleoenvironmental conditions are not independently known for the La Ciénega and lower Wood Canyon formations, the likelihood of different dolomitization models cannot be meaningfully interrogated with the data presented. Nonetheless, we suggest that dolomitization models that involve the advection or convection of seawater or seawater-like fluids at temperatures <40°C (e.g., brine reflux, Kohout convection) are most consistent with the seawater-buffered records preserved in the La Ciénega and lower Wood Canyon Formations. In such models, the seawater flux will vary within the platform, influenced by platform geometry and lithologies (Al-Helal et al., 2012; Caspard et al., 2004; G. D. Jones & Xiao, 2005). We suggest that these controls on fluid flow may explain the differences in the extent of δ44/40Ca alteration observed from the La Ciénega and lower Wood Canyon formations.

Evidence for partial dolomitization is also preserved in the top ~40 m of the Dunfee Member of the Deep Spring Formation, however, in these strata meteoric diagenesis likely also influenced the geochemistry. A transition toward fluid-buffered δ44/40Ca values is recorded towards the top of the Dunfee Member, with dolostone δ44/40Ca values stabilizing at ~−1.1‰, ~20 m below the top contact (fig. 1B). These values are lower than those predicted for fully seawater-buffered carbonates, given the −0.7‰ values reported from the La Ciénega Formation. This suggests meteoric fluids during dolomitization affected the upper Dunfee Member (Holmden et al., 2012; Riechelmann et al., 2023). The presence of a karstic dissolution surface at the base of the Esmeralda Member is consistent with this interpretation. Additionally, the δ18O values of the Dunfee Member are between −25‰ and −10‰, with the coarsely recrystallized dolostones stably recording δ18O values of ~−15‰, depleted compared to dolostones of the lower Wood Canyon and La Ciénega formations (fig. 1B). While the mixing of meteoric and marine waters has been suggested to result in chemically favorable conditions for dolomite formation, kinetic barriers and the requirement of a significant Mg2+ source are argued to prevent significant dolomitization in mixing zones (Hardie, 1987), consistent with the observation that patchy dolomitization is limited to the upper part of the Dunfee Member.

While there is petrographic evidence for later stage dolomitization of the upper Wood Canyon being associated with deep burial (Corsetti et al., 2006), our data suggest that major element carbonate geochemistry, like δ44/40Ca and δ13C, was mostly resistant to these events. For example, dolostones from the top of the Dunfee Member of the Deep Spring Formation at Mount Dunfee preserve nonplanar petrographic textures (fig. S3), which are traditionally interpreted as evidence of crystal growth at >50 °C temperatures associated with burial (Sibley & Gregg, 1987; Woody et al., 1996), although recent work suggests they also may occur at low temperatures (Ryan et al., 2023). Similarly, petrographic data from the upper Wood Canyon Formation at Titanothere Canyon indicates ooid silicification predated dolomitization (Corsetti et al., 2006), which was used to suggest that, at that locality, the Wood Canyon Formation was extensively buried prior to the introduction of dolomitizing fluids. It is, however, unclear whether the lower Wood Canyon Formation at Echo Canyon shares this dolomitization history. Regardless, because the dolostone δ44/40Ca and δ26Mg values presented here are consistent with the stabilization of geochemical records following early dolomitization, we suggest that dolomitization of the dolostone strata in the Wood Canyon and La Ciénega formations occurred early, likely driven by platform brine reflux, and major element dolostone geochemistry was mostly unaffected by later stage recrystallization.

5.2.2. Interpreting the δ18O records

The δ44/40Ca values, δ18O values, and interpreted dolomitization histories of the La Ciénega and lower Wood Canyon formations are consistent with these sites recording seawater values during very early diagenesis. The δ18O values in the Deep Spring Formation are significantly lower than those at the other two sites (figs. 1B and 4A). These low δ18O values of the Deep Spring Formation could either indicate the resetting of the δ18O record with meteoric fluids (plausible for the Dunfee Member which is beneath an exposure surface) and/or at high temperatures. The likely potential for burial diagenesis to reset δ18O values but preserve δ44/40Ca values in limestones has been suggested from modern and ancient environments, assuming sediment-buffered conditions with respect to calcium and carbon during carbonate burial (Ahm et al., 2018, 2021). Thus, for the Esmeralda Member of the Deep Spring Formation, we interpret a scenario in which limestones underwent partial diagenetic stabilization during early marine diagenesis. Final diagenetic stabilization occurred during burial, at which time closed-system conditions with respect to calcium and carbon prevailed. For the Dunfee Member of the Deep Spring Formation – which shows sedimentological evidence for exposure – we suggest that the lower δ18O values could have resulted from meteoric fluids and/or burial diagenesis. This model is consistent with δ238U isotope data from the upper Dunfee Member, which covary with δ44/40Ca data (Chanchai et al., 2026).

5.3. Influence of early marine diagenesis on δ13C records

While δ44/40Ca, δ18O, and δ26Mg proxy records from the three sections of Ediacaran–Cambrian carbonates in southwest Laurentia are consistent with variable alteration by post-depositional diagenetic fluids, we argue that the large scale δ13C trends in these records reflect changes in primary platform seawater isotopic composition. Two lines of evidence suggest that the BACE reflects changes to seawater chemistry rather than marine diagenesis. First, in the Deep Spring and La Ciénega formations, δ13C values approach ~0‰ following recovery from the BACE, regardless of diagenetic regime. Although the full expression of the recovery is not preserved in the Wood Canyon or La Ciénega formations, all three sites preserve δ13C values that return to ~0‰. This recovery of the δ13C values in the La Ciénega Formation is recorded in a fluid-buffered diagenetic regime, in which dolostones record δ13C values of ~0‰ and δ44/40Ca values of up to ~−0.7‰ (fig. 1B). In contrast to this, the δ13C values following the recovery of the BACE in the Deep Spring Formation are relatively sediment-buffered, with limestones recording δ13C values of ~0‰ and δ44/40Ca values as low as ~−1.3‰ (fig. 1B). Diagenetic modeling suggests that seawater-buffered diagenesis will only result in δ13C records that approximate sediment-buffered δ13C values if the concentration and δ13C composition of DIC in seawater is consistent between diagenetic and depositional environments (Lau & Hardisty, 2022). Thus, the preservation of δ13C values of ~0‰ in strata interpreted to record different degrees of δ44/40Ca alteration indicates that the chemistry and concentration of DIC in seawater did not substantially change between precipitation and neomorphism/recrystallization, implying that diagenesis occurred very soon after carbonate deposition.

Second, the Esmeralda Member of the Deep Spring Formation does not preserve features indicative of authigenic carbonate precipitation, suggesting that authigenic carbonate precipitating in the pore-space likely did not play a significant role in driving bulk carbonate δ13C trends (e.g., Schrag et al., 2013). In outcrop, there is no evidence of in-filled void space or authigenic carbonate nodules throughout the member. In thin-section, only one generation of spar is observed from samples that record the BACE (fig. 5), suggesting the presence of neomorphic spar between sand grains, rather than authigenic cements (Bathurst, 1972). It is also unclear if platform redox conditions would have facilitated the anoxic degradation of organic matter required for the precipitation of authigenic carbonate with low δ13C values, given that the BACE is reported from platform carbonates (e.g., sandy limestones of FA5; fig. 5). Bulk carbonate δ13C values reported from the Esmeralda Member are therefore interpreted to largely record the δ13C composition of carbonate minerals originally precipitated from seawater. Collectively, these lines of evidence suggest that the BACE was not driven by changes in diagenesis regimes and authigenic mineral precipitation, but instead by changes to the terminal Ediacaran platform seawater DIC pool.

Although the large magnitude δ13C trends are not interpreted to result from diagenetic overprinting, fluctuations in the diagenesis regimes recorded at each site are interpreted to have minor (<2‰) effects on δ13C records. In a scenario where the δ13C values of pore-fluids and seawater are similar, aragonite-to-calcite neomorphism is still expected to have different effects on bulk carbonate δ13C values under different diagenetic regimes (Ahm et al., 2025). In a sediment-buffered regime (with respect to carbon), secondary calcite is expected to preserve the δ13C value of the primary aragonite. However, in a fluid-buffered regime, secondary calcite will record the δ13C value of pore-fluid plus the fractionation factor associated with calcite. As aragonite fractionates δ13C values more strongly (~2.7‰) than calcite (~1‰), the transformation of aragonite to calcite under fluid-buffered conditions in seawater with the same δ13C value of DIC should result in a ~1.7‰ decline in the δ13C value of the sediment (Romanek et al., 1992). This scenario matches observations from our study sites. In the top ~60 m of the Deep Spring Formation, there are fluctuations between more sediment-buffered (~−1.3‰) and seawater-buffered (~−0.8‰) δ44/40Ca values, coinciding with a decrease in δ13C values from ~−0.2‰ to ~−2.5‰ (fig. 1B).

5.4 Influences of relative sea-level change, facies, and volcanism

It is unclear what mechanism promoted fluid-buffered diagenetic alteration across the margin during the BACE event, although porous, shallow water carbonate platforms are environments inherently prone to this style of diagenesis. Sedimentation rate has been suggested to control diagenetic regimes in marine environments (e.g., Higgins et al., 2018; L. L. Nelson et al., 2022), but the role of sedimentation rate in shaping the geochemical records of the La Ciénega, Wood Canyon, and Deep Spring formations is unknown, given the few radiometric age constraints that currently exist for these strata (Hodgin et al., 2021; L. L. Nelson et al., 2023). On other ancient carbonate platforms, greater proximity to shoreline is observed to correspond to higher degrees of alteration of carbonate geochemical records (Busch et al., 2022, 2023; Higgins et al., 2018; D. S. Jones et al., 2020). A similar control may explain the transition toward seawater-buffered δ44/40Ca values corresponding with parts of the descending limb of the BACE that are associated with relative sea level falls. However, shallowing trends and facies associations do not consistently track the δ44/40Ca variation recorded in the Esmeralda Member, which spans multiple transgressive-regressive cycles (fig. 5; Smith et al., 2023).

The physical properties of platform sediments can also determine diagenesis regime, as sediment porosity and permeability strongly affect platform circulation during early marine and meteoric diagenesis (e.g., Sanford et al., 1998). An increase in siliciclastic content among and within carbonate beds like that recorded alongside the BACE in the Deep Spring and La Ciénega formations may reflect such a control on diagenesis regime (figs. 1B and 5). However, the porosities and permeabilities of carbonate and siliciclastic sediments in marine diagenetic environments vary dramatically depending on factors like the size of carbonate grains and the extent of carbonate cementation at the time of marine diagenesis (Ehrenberg & Nadeau, 2005; Enos & Sawatsky, 1981; Moore, 1989), which cannot directly be constrained from the sedimentary records of the Deep Spring and La Ciénega formations. Nonetheless, transitions between different facies associations over the Esmeralda Member do not correspond to any coherent trends in δ44/40Ca values (fig. 5). Moreover, there is no strong evidence of a similar stratigraphic change in carbonate porosity or permeability in the lower Wood Canyon Formation, either because no change occurred or because later diagenesis (under sediment-buffered conditions) destroyed evidence of variation in carbonate facies.

We speculate that the increased fluid-buffered alteration across the BACE in southwestern Laurentia could be driven by the emplacement of volcanic dikes and sills that are genetically related to rift-related crustal thinning and faulting along the southwestern margin of Laurentia. A widespread increase in marine diagenesis could be explained by the circulation of hot seawater through carbonate platforms driven by dikes and sills in the subsurface. This mechanism is similar to Kohout driven convection but with a more powerful heat source. The geologic evidence for this hypothesis is limited, but not entirely speculative. Of the three sections studied, only the Caborca section has Ediacaran–Cambrian aged syndepositional basalts and volcaniclastics within it. The La Ciénega Formation also has the strongest evidence for early marine dolomitization (consistently fluid-buffered δ44/40Ca values; fig. 2), implying that they were relatively proximal to the fluid source. Some of these basalts and volcaniclastics are found within the strata recording the BACE, but the thicker intervals of basalt and volcaniclastics occur in the Cerro Rajón Formation, the unit overlying the La Cienéga Formation (Barrón-Díaz et al., 2019; Hodgin et al., 2021; Stewart et al., 1984). Although there are no Ediacaran–Cambrian volcanics in the two other sections studied, there are basalt intervals within the latest Ediacaran–early Cambrian Stirling Quartzite and lower member of the Wood Canyon Formation farther north in Nevada (Smith et al., 2023; Stewart, 1970). This observation is consistent with the fact that the Deep Spring Formation is predominantly limestone while the Wood Canyon Formation is dolomitized, with slightly more sediment-buffered δ44/40Ca values than in the La Ciénega Formation, implying a more distal relationship to the fluid source. This model for the emplacement for volcanic dikes and sills concomitant with the BACE is also consistent with positive Eu anomalies (Eu/Eu* >1.5) that occur at the nadir of the BACE in the Mount Dunfee and Cerro Rajón sections, potentially reflecting a regional input of hydrothermally sourced rare earth elements (Chanchai et al., 2026).

5.5. What does the BACE record?

Because the BACE is consistently preserved across >1000 kms and spanning multiple sequence boundaries in a continuum of more sediment- to more fluid-buffered diagenetic conditions in southwestern Laurentia, we suggest that this carbon isotope excursion primarily reflects secular trends in platform seawater DIC composition. Among the three studied successions, sequence stratigraphy and biostratigraphy offer independent methods of correlation demonstrating that – even without precise radioisotopic constraints – the BACE occurs at generally the same time in all three sections. The carbonate strata recording the BACE in southwest Laurentia have clearly been altered through diagenesis. However, if these diagenetic fluids had played a major role in affecting the δ13C of these strata, we would expect to see variable δ13C values that correlate to the different diagenetic fingerprints. Instead, we document consistent δ13C values preserved among the three study sites, and thus, the most parsimonious explanation of the δ13C values of the BACE is that, in southwest Laurentia, they reflect platform seawater composition. It remains difficult to interpret whether this platform seawater reservoir was well mixed with the rest of the ocean.

If the BACE is recording a perturbation in a local DIC pool, then it could be explained by a shift in platform conditions. In modern evaporation pans, microbial mat productivity promotes disequilibrium between the concentrations of inorganic carbon in the seawater brine and the atmosphere, leading to the invasion of atmospheric CO2 (Lazar & Erez, 1992). Kinetic isotope effects related to CO2 hydration result in low (~−9‰) DIC δ13C values (Lazar & Erez, 1992). Analogous processes have been hypothesized to occur on Neoproterozoic platforms where shelf-to-slope heterogeneity in the expression of large, negative δ13C excursions is documented (Ahm et al., 2021; Busch et al., 2022). The BACE may similarly record an episode of enhanced platform productivity at the Ediacaran–Cambrian boundary. While such a scenario is highly speculative, high rates of productivity are associated with mass extinction and biotic turnover among primary producers in the Phanerozoic (Van De Schootbrugge & Gollner, 2013), implying a possible causal relationship between the BACE and potential ecological change in the terminal Ediacaran. One issue with interpreting the BACE in this way is the large spatial distance (~1000 km) over which the excursion is preserved in southwest Laurentia. Another issue is that there is no sedimentological evidence (e.g., evaporite pseudomorphs) that support the deposition of these strata within evaporitic environments. An arguably bigger issue is that there is little stratigraphic scatter in δ13C values, a chemostratigraphic pattern that would be expected if the δ13C values were the result of local isotope reservoir effects like CO2 invasion.

In contrast to previous models proposed to explore triggers of the BACE and other large Neoproterozoic negative carbon isotope excursions, our data indicate a potential link between widespread changes in the δ13C values of DIC and an increase in early fluid-buffered marine diagenesis of platform carbonates. As suggested above, one mechanism which could produce a widespread perturbation to the DIC pool and could be linked to an increase with marine fluid circulation in platform environments, involves magmatism associated with the rifting of the southwestern margin of Rodinia (Hodgin et al., 2021; Smith et al., 2023). In this model, rift-related dikes and sills intruded organic-rich strata and/or methane clathrates, resulting in the release of isotopically light carbon (Hodgin et al., 2021). While no physical evidence of organic-rich strata and/or methane clathrates exists, there are late Ediacaran to early Cambrian basaltic sills in southwest Laurentia and a recently recognized Ediacaran–Cambrian large igneous province, the Wichita volcanics in southern Oklahoma; recent geochronology progress has demonstrated a broad temporal overlap between at least some of these igneous bodies and the Ediacaran–Cambrian boundary (Hodgin et al., 2021; L. L. Nelson et al., 2023; Smith et al., 2023; Wall et al., 2021). Additionally, in Caborca, the basaltic sills preserve chemistries consistent with crustal thinning during rifting (Barrón-Díaz et al., 2019; Tapia-Trinidad et al., 2022). Large igneous provinces have been repeatedly implicated in the generation of Phanerozoic negative δ13C excursions and initiation of mass-extinction events (e.g., Berndt et al., 2023; Ruhl et al., 2011; Svensen et al., 2009; Wignall, 2001). The generation of the BACE and roughly coeval disappearance of Ediacaran faunal clades have been suggested to be analogous to these better constrained δ13C excursions and mass extinctions (Hodgin et al., 2021; Smith et al., 2023).

6. CONCLUSIONS

Here, we assess the influence of marine diagenesis on the BACE along the western margin of Laurentia, the region from which it was first interpreted to mark the Ediacaran–Cambrian boundary. We find that the δ44/40Ca values of the three studied sections record different degrees of mostly marine diagenetic alteration. The dolostone δ26Mg and δ18O values suggest that this diagenetic alteration occurred prior to significant burial. Despite the variability in δ44/40Ca and interpreted type of diagenesis (i.e., more sediment- vs more fluid-buffered), the first order δ13C chemostratigraphic trends are very similar between the three sections. There is smaller scale (<2‰) δ13C variability among the sections, and, additionally, the Mount Dunfee section shows the most prevalent point-to-point variability among δ13C data, while also showing the most stratigraphic variability in δ44/40Ca data. Thus, we suggest that this smaller scale δ13C variability can be attributed to stratigraphically variable patterns of early marine diagenesis which is in turn controlled by factors such as local base level and porosity. These changes in diagenesis were not responsible for the large, first-order, and regionally reproducible shifts in δ13C across the BACE, which can instead be attributed to changes in platform seawater composition.

Ultimately, from the synthesis of δ13C, δ44/40Ca, δ26Mg, δ18O, and Sr/Ca records, we interpret a scenario in which seawater-buffered diagenesis occurred soon after the primary precipitation of aragonite, implying that the carbonates faithfully capture the δ13C composition of platform seawater DIC, which fluctuated to below-mantle values during the BACE. In this interpretation, seawater-buffered diagenesis did not generate a δ13C excursion where one previously did not exist. Instead, it coincided with an interval of 13C depletion in DIC in shallow marine environments and, potentially, in the global ocean.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Nicolas Slater and Stefania Gill for their assistance in the lab. We thank Blake Hodgin for field assistance in Sonora. EFS acknowledges support from the National Science Foundation (NSF EAR-1827669 and NSF EAR-2021064), the Sloan Research Fellowship (#FG-2021-16049), and the Johns Hopkins Catalyst Award. We thank N. Planavsky, T. Dahl, two anonymous reviewers, and Associate Editor L. Derry who significantly improved the quality of this manuscript.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

A.C.A., J.A.H., and E.F.S. designed the study. L.L.N and E.F.S. collected the samples used in the study and provided geologic background context. M.C.L., J.W.T., and A.C.A. conducted the lab analyses for the study. M.C.L. wrote the initial draft of the manuscript with input from all coauthors. E.F.S. and J.A.H. raised funding for the work.

DATA AND SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

The attached supplementary material provides extended methods for additional minor and trace element (Mn/Ca and U/Ca) data, as well as for calcium and magnesium isotope analyses. It provides additional figures presenting δ44/43Ca and δ44/42Ca and δ25/24Mg and δ26/24Mg values from the Deep Spring, Wood Canyon, and La Ciénega formations (fig. S1), Mn/Ca and U/Ca ratios from the Deep Spring, Wood Canyon, and La Ciénega formations (fig. S2), a photomicrograph displaying nonplanar dolomite texture from the top of the Dunfee Member of the Deep Spring Formation (fig. S3), and δ44/40Ca and δ13C values from the Deep Spring Formation color-scaled by facies associations and stratigraphic height (fig. S4).

Data are available through the Johns Hopkins Research Data Repository at https://doi.org/10.7281/T1/IM9BZI.

Editor and Associate Editor: Louis A. Derry

_locality_map_for_study_sites._study_sites_include_(1)_mount_dunfee_in_esmeralda_county.png)

_cross-plots_of__44_40_ca_and__13_c_records_from_the_deep_spring__wood_canyon__and_la.png)

_cross-plots_of__18_o_and__44_40_ca_records_from_the_deep_spring_formation__wood_cany.png)

_locality_map_for_study_sites._study_sites_include_(1)_mount_dunfee_in_esmeralda_county.png)

_cross-plots_of__44_40_ca_and__13_c_records_from_the_deep_spring__wood_canyon__and_la.png)

_cross-plots_of__18_o_and__44_40_ca_records_from_the_deep_spring_formation__wood_cany.png)