1. Introduction

The early Cambrian marks an interval of rapid evolution, in which the majority of extant animal phyla diversified to occupy a wide range of marine environments, leading to a fundamental shift in the character of global ecosystems (Briggs, 2015). While the preceding Ediacaran Period marks the earliest compelling evidence for widespread metazoans (e.g., Droser & Gehling, 2015; Dunn et al., 2021; Knoll & Carroll, 1999; Narbonne, 2005), including evidence for motility in the form of trace fossils (e.g., Jensen et al., 2006; Seilacher et al., 2005), and the onset of animal biomineralization (e.g., Germs, 1972a; Grotzinger et al., 2000; Penny et al., 2014), the affinities of many Ediacaran organisms are still poorly understood. The succeeding early Cambrian is marked by the first appearance of numerous animal phyla that persist into the present day, thus marking a major step-change in Earth history and – arguably – the onset of the more modern-looking marine biosphere. By c. 518 Ma, much of the diversification of Eumetazoa had occurred, as evidenced by ~17 extant metazoan phyla preserved within the Chengjiang Lagerstatten (Hou et al., 2017; Yang et al., 2018). High-resolution biostratigraphic records spanning the Ediacaran–Cambrian transition are thus critical to our understanding of early animal evolution; however, significant challenges remain in correlating, defining, and calibrating a unified global late Ediacaran to early Cambrian geologic time scale.

The base of the Cambrian Period is currently defined by the first appearance of an ichnotaxonomic assemblage that includes the trace fossil Treptichnus pedum, with the Global Boundary Stratotype Section and Point (GSSP) located at the Fortune Head section in Newfoundland, Avalonia (Brasier et al., 1994; Buatois, 2018; Landing, 1994; Peng et al., 2012). Originally assigned to Phycodes pedum (Seilacher, 1955), T. pedum is thought to record the feeding trace (‘fodichnion’) of a bilaterian and vermiform metazoan, with some studies suggesting a tracemaker of priapulan affinity (Buatois, 2018; Jensen, 1997; Seilacher, 1955; Turk, Wehrmann, et al., 2024; Vannier et al., 2010). The burrow itself possesses a complex 3D architecture, characterized by a horizontal and subsurface master burrow with regular branches (‘probes’) oriented oblique to the bedding plane, and which reach up towards the sediment-water interface. As a predominantly subsurface burrow, T. pedum is thus most frequently found preserved on the underside of beds where it is commonly expressed as trail of offset, serial almond-shaped sediment lobes projecting through the base of laminae, and actively backfilled with sediment derived from the overlying layers (Seilacher, 2007). The use of T. pedum as a biostratigraphic marker has come under criticism – principally due to the possibility of facies control. These criticisms have led some workers to instead propose using a Treptichnus pedum Ichnofossil Assemblage Zone (‘IAZ’) to recognize this stratigraphic boundary (an assemblage of trace fossils which, alongside T. pedum, includes the first occurrences of Skolithos annulatus, Arenicolites sp., and Monomorphichnus spp.; Babcock et al., 2014; Landing, 1994; Landing et al., 2013; Narbonne et al., 1987). However, to date this criterion has not been universally adopted, and defenses have been mounted in support of T. pedum as a valid biostratigraphic marker (Buatois, 2018).

In Avalonia, the base of the T. pedum zone is constrained to >531 Ma by c. 531 Ma zircon U-Pb dates within strata correlating to the overlying Rusophycus avalonensis zone (Barr et al., 2023; Isachsen et al., 1994). In Nevada, the first regional occurrences of ichnotaxa of the T. pedum assemblage are constrained to <533 Ma by a maximum depositional age in the lower member of the Wood Canyon Formation (Nelson et al., 2023). Further work is required to understand whether this approximates the global FAD of T. pedum, and thus the base of the Cambrian Period. This is in part due to a significant discrepancy between this and a proposed age for the Ediacaran–Cambrian boundary in Namibia: 538.8–538.6 Ma (Linnemann et al., 2019). This tightly bracketed age range for the proposed base of the Cambrian is based upon two results: (1) in Namibia, T. pedum has been well documented from strata correlated to the Nomtsas Formation (Grotzinger et al., 1995; Wilson et al., 2012); and, (2) the Nomtsas Formation has been dated via high precision U-Pb geochronology of ash beds at two localities (Linnemann et al., 2019; Nelson et al., 2022). Critically, these paleontological and geochronological datasets come from localities that are >50 kilometers apart. Previous work has highlighted that there exists significant uncertainty regarding the relationships and correlations between lithological units among these localities (Nelson et al., 2022), and therefore, despite a rich fossil record and the presence of numerous dated horizons, the position and age of the Ediacaran–Cambrian boundary in the Nama Group is still unknown.

With the goal of improving stratigraphic and biostratigraphic clarity and understanding of the precise placement of the Ediacaran–Cambrian boundary in the Nama Group, we interrogate precise correlations between geochronologically calibrated strata and those containing biostratigraphically critical trace fossils. Furthermore, we provide a regional tectono-stratigraphic framework for understanding the upper Schwarzrand Subgroup and the transition into the Fish River Subgroup that will help focus further research on the Ediacaran–Cambrian transition in the Nama Group, the evolution of this foreland basin system, and global calibration of the base of the Cambrian and tempo of early animal radiation.

2. Geologic Background

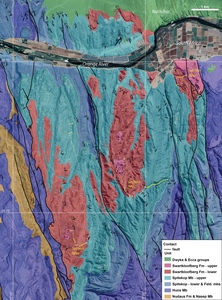

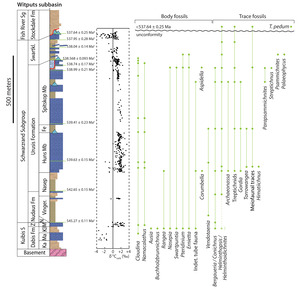

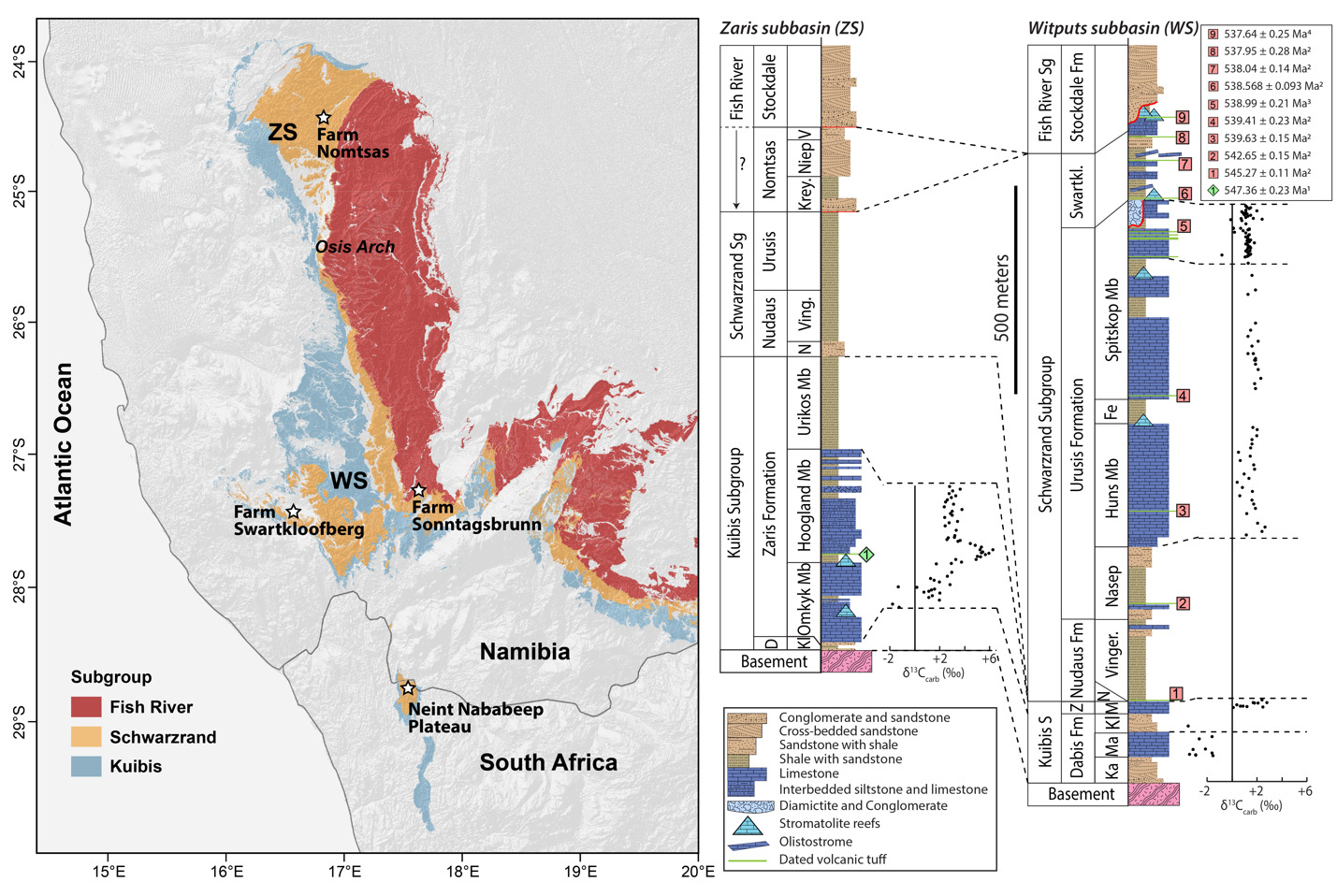

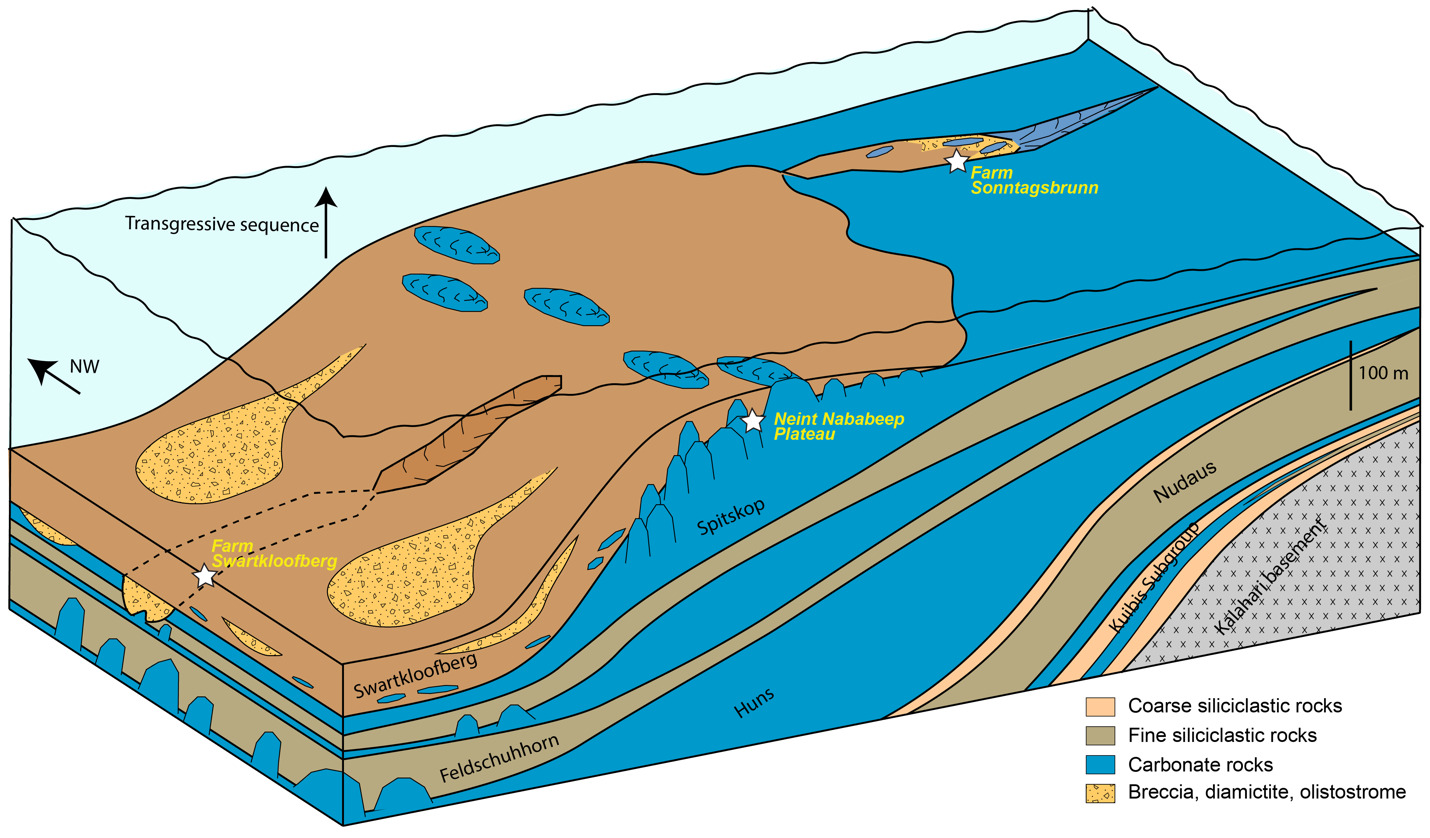

The Nama Group, exposed in Namibia and northwestern South Africa, was deposited in a foreland basin on the Kalahari Craton that formed in response to continental flexure associated with the ENE-trending Damara orogen, between the Kalahari and Congo cratons, and the NNW-trending Gariep orogen, between the Kalahari and Rio de Plata orogens (modern geographic reference frame) (fig. 1; e.g., Germs, 1995; Germs & Gresse, 1991; Gresse & Germs, 1993; Grotzinger & Miller, 2008). These orogenic belts are part of the broader Ediacaran–Cambrian Pan-African orogen that led to the assembly of the Gondwana supercontinent (e.g., Germs, 1995; Germs et al., 2009). The Nama Group has been divided into the Kuibis, Schwarzrand, and Fish River subgroups (fig. 2; Germs, 1983). The stratigraphy of the Kuibis and Schwarzrand subgroups differs markedly between central and southern Namibia, which led to definition of two distinct subbasins, the Zaris in the north and the Witputs in the south (Germs, 1983). During deposition of the Kuibis subgroup, these were divided by an ENE-trending topographic paleohigh of Mesoproterozoic basement, known as the Osis Arch. The Kuibis subgroup is thicker and more carbonate-dominated in the Zaris Subbasin compared to the Witputs Subbasin. Conversely, outcrops of the Schwarzrand subgroup are thicker and more carbonate-dominated in the Witputs Subbasin (Germs, 1983).

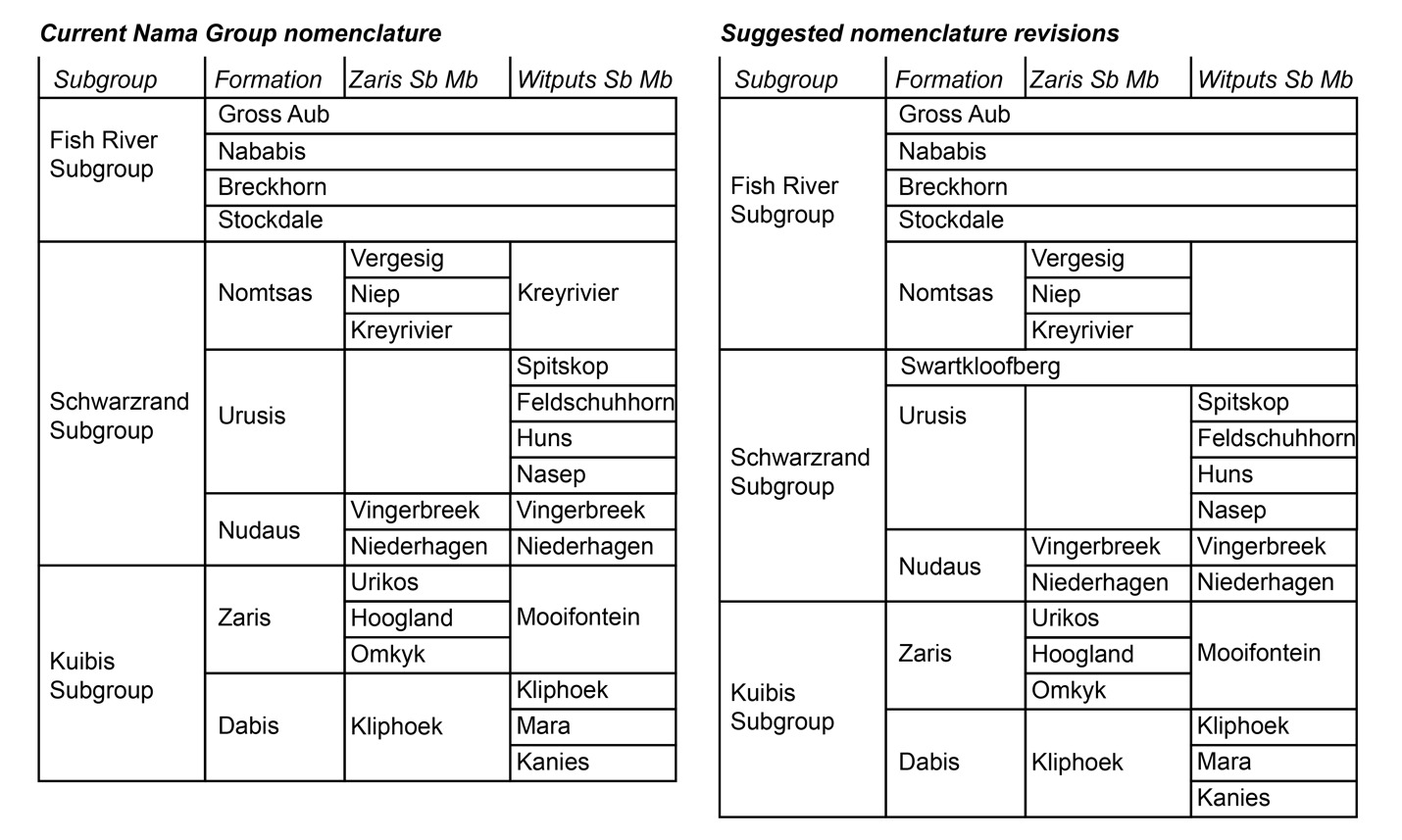

The Nomtsas Formation of the Schwarzrand Subgroup was originally defined as the “terminal Clastic Member of the Schwarzrand Formation” (Germs, 1972b), before being separated as a formation (named for Nomtsas Farm in the Zaris Subbasin). This unit was defined by Germs (1983) as containing three members: the Kreyrivier, Niep, and Vergesig members. These members are defined in the Zaris Subbasin where they are readily distinguishable in aerial imagery, and only the Kreyrivier Member extends to the Witputs Subbasin. However, the Kreyrivier Member is described as having very different facies in the northern versus southern subbasins. In the north, it includes raindrop impressions, desiccation cracks, ripple marks, and cross-bedded sandstone (Grotzinger & Miller, 2008). It is described as transitioning to more distal depositional settings in the south, dominated by siltstone and shale (Germs, 1983). Much of the remainder of this paper will be devoted to describing strata previously attributed to Kreyrivier Member in the Witputs Subbasin. The overlying Niep Member is trough cross-bedded sandstone deposited in a braided fluvial environment, while the Vergesig Member comprises interbedded sandstone and shale (Grotzinger & Miller, 2008). Germs (1983) noted that the “northern” Nomtsas Formation in the Zaris Subbasin are red-bed facies that are very similar to the overlying Fish River Subgroup. These upper two members of the Nomtsas Formation are not recognized in the Witputs Subbasin, where cross-bedded sandstone of the basal Stockdale Formation of the Fish River Subgroup directly overlie either the Nomtsas or Urusis formations of the Schwarzrand Subgroup (Germs, 1983; Grotzinger & Miller, 2008). In the Witputs Subbasin, the Fish River Subgroup includes four fining-upward cycles that transition from fluvial sandstone into heterolithic, shale-rich tidal deposits (Germs, 1983; Geyer, 2005).

3. Methods

Outcrops previously mapped and/or described as Nomtsas Formation in the Witputs Subbasin were visited at localities including Farm Swartkloofberg (e.g., Saylor & Grotzinger, 1996), Farm Sonntagsbrunn (e.g., Wilson et al., 2012), and the Neint Nababeep Plateau (Nelson et al., 2022) (fig. 1). In addition, outcrops of the Nomtsas Formation within its type area (Farm Nomtsas) in the Zaris Subbasin were investigated and documented. Detailed geologic mapping was conducted at variable scales using the Midland Valley FieldMove digital mapping application. Detailed stratigraphic sections were measured with a folding meter stick. Body and trace fossils and sedimentary facies were photographed in the field using a Nikon D3300 and 18–55mm lens.

Carbonate hand samples were collected from select sections on the Neint Nababeep Plateau for carbon isotope chemostratigraphy. At Johns Hopkins University, these were cut with a rock saw, and ~5 mg aliquots of powder were microdrilled from fresh faces, along laminations and avoiding veins, vugs, and siliciclastic grains. Carbon isotope (δ13C) and oxygen isotope (δ18O) values were measured using a Thermo-Finnigan MAT253 isotope ratio mass spectrometer in continuous flow mode coupled to a GasBench II peripheral device. Approximately 0.3 mg of sample powder in He-purged vials were reacted overnight with 100% phosphoric acid at 30 °C, and then emitted CO2 gas was analyzed against tank CO2 gas. Isotopic measurements were normalized using in-house carbonate standards (ICM, Carrara Marble, IVA, Analysentechnik, calcium carbonate) calibrated against international standards (NBS-18 and IAEA-603). For in-house standards, standard deviations (1σ) of δ13C values were <0.05‰ and of δ18O values were <0.3‰. Data results are provided in the Data and Supplementary Information (table SI2).

At MIT, U-Pb geochronology by the chemical abrasion-isotope dilution-thermal ionization mass spectrometry (CA-ID-TIMS) method was carried out on five single zircon crystals separated from a silicified ash bed collected from the Neint Nababeep Plateau (E2107) (fig. SI1B–D). Zircons were separated from the crushed and sieved sample using magnetic and density separation. Grains selected for analysis were annealed at 900 °C for 60 hours, chemically abraded in purified 29 M HF at 210 °C for 12 hours using methods modified after Mattinson (2005), fluxed successively in 3.5 M HNO3 and 6 M HCl on a hot plate (and rinsed with MQ water after each step to remove leachates), loaded into individual PFA microcapsules and spiked with the EARTHTIME ET535 205Pb-233U-235U±202Pb tracer solution (Condon et al., 2015; McLean et al., 2015), and dissolved in 29 M HF at 210 °C for 48 hours. Following dissolution, purified U and Pb were separated from each microcapsule using an HCl-based anion exchange column chemistry procedure modified after Krogh (1973), and were loaded together onto an outgassed Re filament in a silica gel/phosphoric acid mixture. Ratios of U and Pb isotopes were measured on an IsotopX X62 multi-collector thermal ionization mass spectrometer equipped with a Daly photomultiplier ion counting system. Pb isotopes were measured on the ion counter as mono-atomic ions using a peak hopping mode and were corrected for mass dependent fractionation using the 205Pb/202Pb of the tracer or using an independently derived fractionation correction of 0.18% ± 0.05% per atomic mass unit (2σ). U isotopes were measured as dioxide ions in static mode using three Faraday collectors, subjected to a within-run mass fractionation correction using the 233U/235U ratio of the tracer and a sample 238U/235U ratio of 137.818 ± 0.045 (Hiess et al., 2012), as well as an oxide correction based on an 18O/16O ratio of 0.00205 ± 0.00005. Five single zircons were analyzed and Pb and U isotopic data are given in table SI1. Data reduction, calculation of dates, and propagation of uncertainties used the Tripoli and ET_Redux applications and algorithms (J. F. Bowring et al., 2011; McLean et al., 2011). The measured 206Pb/238U dates were corrected for initial 230Th disequilibrium based on a magma Th/U ratio of 2.8 ± 1.0 (2σ). The age of this volcanic ash bed was calculated based on the weighted mean of a statistically coherent cluster of four zircon 206Pb/238U dates, after excluding a single older analysis interpreted to represent a detrital or xenocrystic zircon. Uncertainties on the weighted mean dates are given at 95% confidence level (2σ) and in the ± x / y / z Ma format, where x is the internal error based on analytical uncertainties only, y includes the tracer calibration uncertainty, and z includes y plus the 238U decay constant uncertainty of Jaffey et al. (1971). Data results are summarized in the Data and Supplementary Information.

4. Results

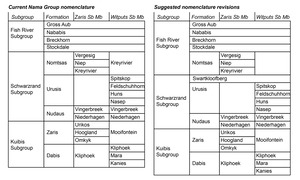

Herein, we argue that strata previously described as the Nomtsas Formation in the Witputs Subbasin (e.g., Germs, 1983; Grotzinger et al., 1995; Grotzinger & Miller, 2008; Nelson et al., 2022; Saylor & Grotzinger, 1996) are distinct from those in the Zaris Subbasin, containing very different lithologies, deposited in distinct depositional and tectonostratigraphic environments, and likely deposited asynchronously. Given that Farm Nomtsas is located in the Zaris Subbasin, hereafter we distinguish these uppermost strata of the Schwarzrand Subgroup in the Witputs Subbasin as the Swartkloofberg Formation, named for exceptional exposures on Farm Swartkloofberg (e.g., Saylor & Grotzinger, 1996). While our reasoning for revising the nomenclature of these strata is given in the Results and Discussion sections, we introduce this nomenclature here for clarity (fig. 2).

4.1. Neint Nababeep Plateau

4.1.1. Lithostratigraphy and geochronology of the terminal Schwarzrand Subgroup, Neint Nababeep Plateau

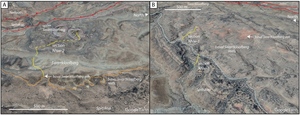

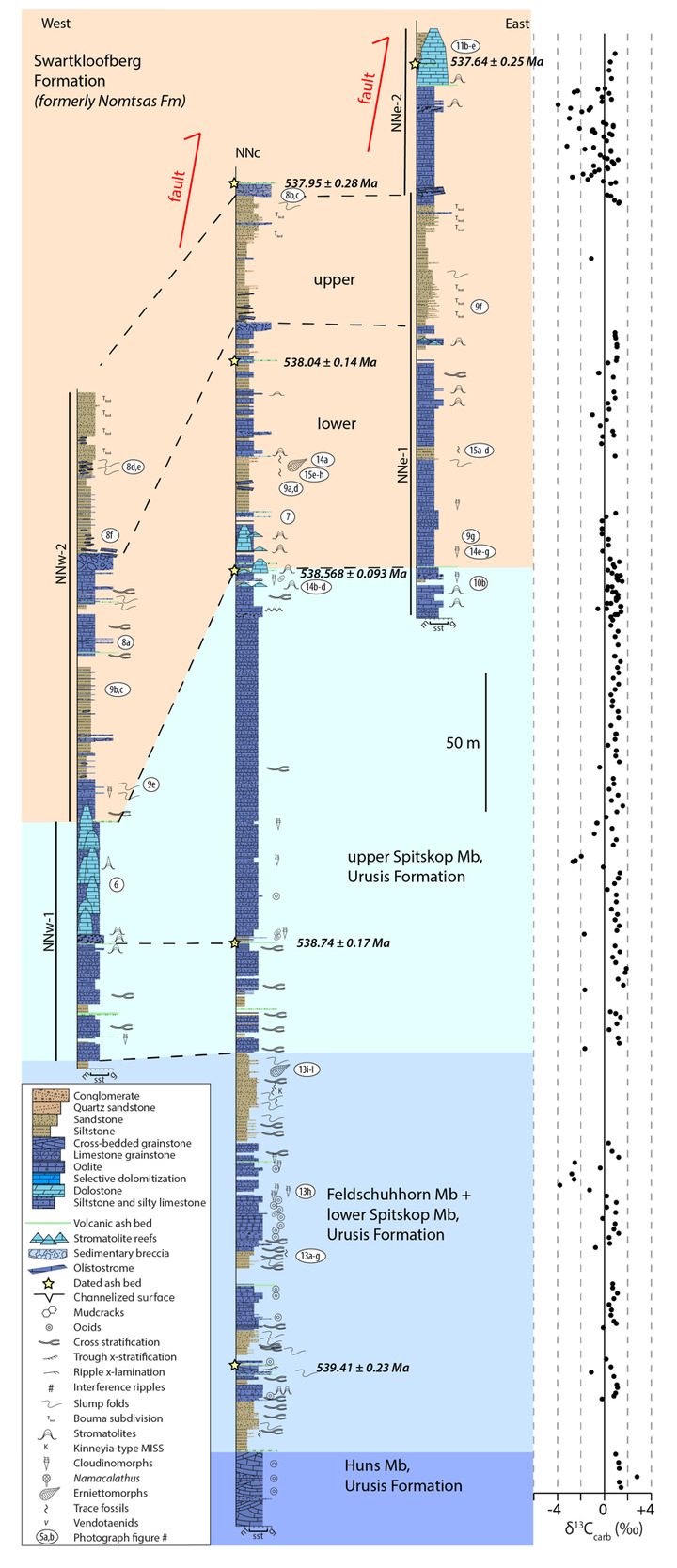

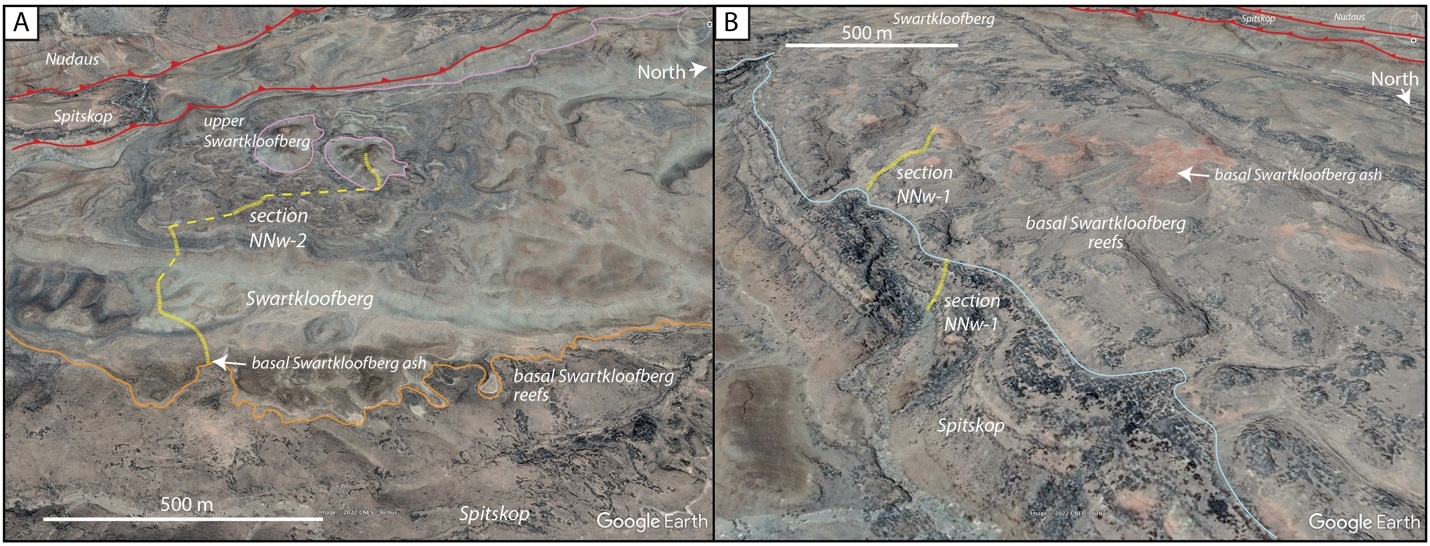

On the Neint Nababeep Plateau of northwestern Republic of South Africa, the Swartkloofberg Formation is exposed over ~6 km, and across three distinct fault blocks separated by NNW-trending, high-angle faults (fig. 3). There is considerable stratigraphic and lateral variability in this unit, even across relatively short distances (fig. 4). Within each of the exposure areas (here labeled NNw, NNc, and NNe from west to east, respectively), there is an apparently conformable and gradational contact between the upper Spitskop Member of the Urusis Formation and the lower Swartkloofberg Formation. Each of these sections is described below. The Swartkloofberg Formation is the highest exposed stratigraphic unit of the Nama Group in each of these fault blocks. On the north side of the Orange River in Namibia, exposures of the Nama Group, including the Swartkloofberg Formation are unconformably overlain by glacial diamictite of the upper Paleozoic Dwyka Group. Locally, small outcrops and talus of the Dwyka Group are also found overlying the Nama Group on and adjacent to the Neint Nababeep Plateau south of the Orange River.

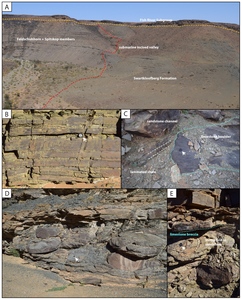

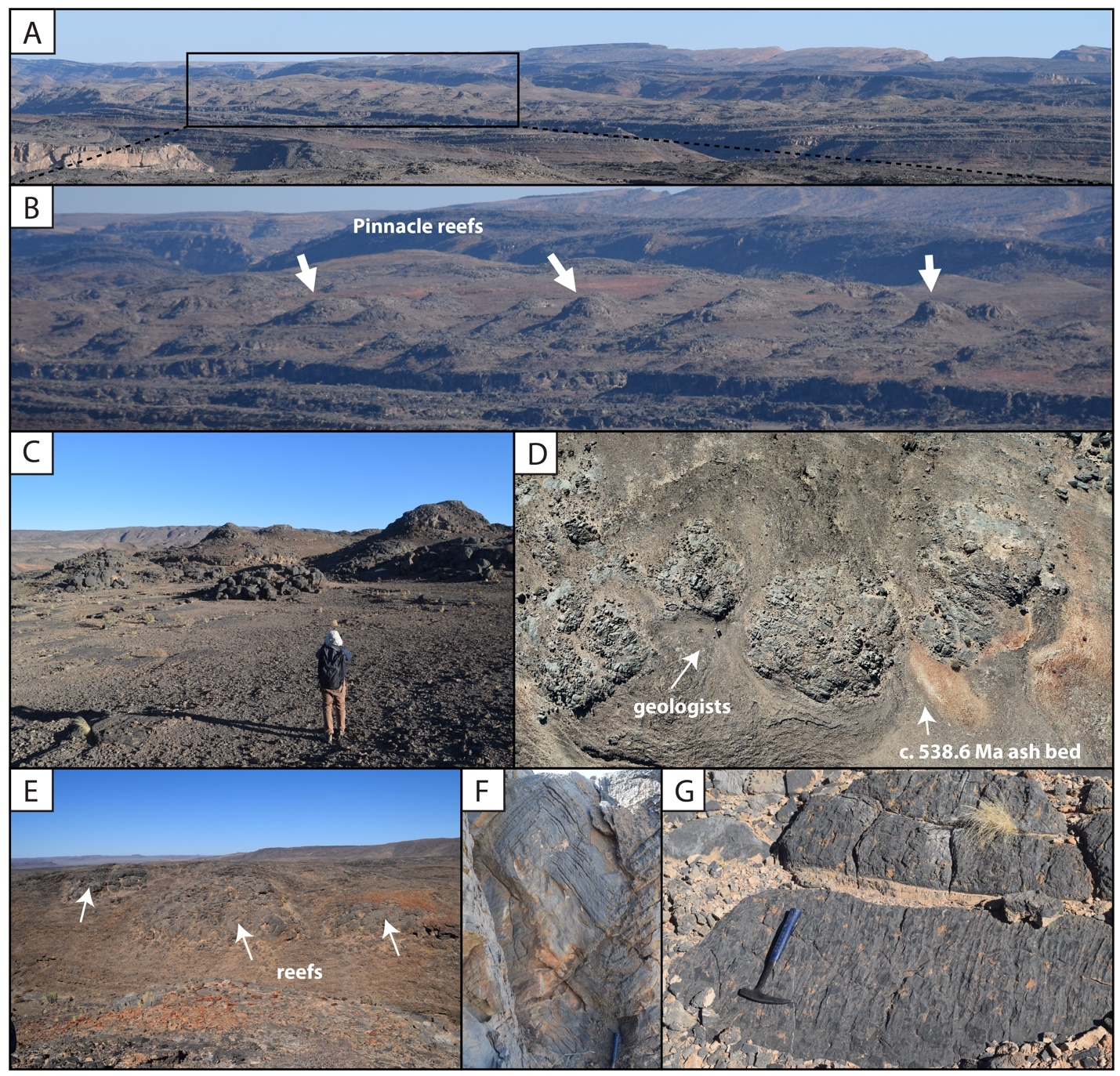

In section NNw, the limestone-dominated upper Spitskop Member is approximately 90 m thick (figs. 4, 5). Of this, the lowest 40 meters is predominantly bedded grainstone to packstone (some cross-stratified) with thinner intervals of siltstone and silty limestone. Based on detailed lithostratigraphic and ash bed correlations of the upper Spitskop Member (fig. 4), a prominent silicified ash bed at the top of this interval can be confidently correlated to a silicified ash bed in the NNc section, which was previously dated at 538.74 ± 0.17 Ma (figs. 4, SI1A; Nelson et al., 2022). The remaining c. 50 meters of the upper Spitskop Member preserves high-relief stromatolite reefs with reef bases growing off of four or more distinct stratigraphic horizons (fig. 6). The largest preserved reefs reach vertical relief of at least 20 meters. Reefs comprise stacked stromatolites that range in form from domal to conical (fig. 6F). Individual stromatolites are up to several meters in diameter, and often have cores with thrombolitic textures or amalgamations of cm-scale digitate stromatolites, both of which are locally selectively dolomitized (fig. 7D–E). Microbialite laminations on reef edges generally have moderate to steep dips away from the reef centers. Inter-reef sediment is predominantly onlapping silty limestone and is preferentially eroded such that much of the modern exposure of these represents primary late Ediacaran reef topography. Tongues of reef-derived limestone talus breccia are preserved adjacent to high-relief reefs (fig. 6G). Unlike reefs of the Huns Member at Farm Swarkloofberg or those of the Kuibis Subgroup, Cloudina and Namacalathus shelly material were not observed in association with the stromatolites or thrombolites of this interval, although circular cross-sections of probable Cloudina are preserved in silty packstone of inter-reef sediment. A prominent orange-weathering silicified ash bed onlaps upper horizons of this reef interval, and, based on its lithostratigraphic/sequence stratigraphic position, we suggest this ash bed correlates to an ash bed in section NNc at the Spitskop-Swartkloofberg contact, which was dated at 538.568 ± 0.093 Ma (figs. 4–6; Nelson et al., 2022).

This ash bed and thinly interbedded silty limestone and siltstone onlap the upper reefs as part of a gradational transition into the Swartkloofberg Formation. This lower interval of the Swartkloofberg Formation preserves parallel and low-angle cross laminations, as well as several horizons of slump folds and intra-clast conglomerates. Rare outsized stromatolite clasts are likely derived from adjacent updip reefs. Horizons of packstone preserve circular cross-sections of shelly fossils, which are interpreted as Cloudina based on similar morphology to tubular fossils in the correlative interval in sections NNc and NNe that preserve funnel-in-funnel structure. Up-section, the Swartkloofberg Formation includes intervals of siltstone, thin bedded silty limestone, beds of carbonate clast sedimentary breccia (fig. 8A), diamictite, and olistostrome, and at least two additional silicified ash beds. These ash beds were not dated but, based on their lithostratigraphic position, one of them likely correlates to an ash bed dated at 538.04 ± 0.14 Ma in section NNc (fig. 4; Nelson et al., 2022). The lower and upper parts of the Swartkloofberg Formation are siliciclastic dominated, separated by an interval of carbonate dominated strata. Bedding structures include parallel laminations, low-angle cross laminations, slump folds, and flute marks (fig. 9B–C, 9E). The uppermost exposed strata (above which the section skies out at the top of the plateau) are sandstone turbidites preserving graded beds, planar and ripple cross laminations, as well as intervals of carbonate clast diamictite (fig. 8D–F). The entire exposed section of the Swartkloofberg Formation is ~150 m.

To the east, within section NNc, carbonates of the upper Spitskop are >50 m thicker than in section NNw and are dominated by grainstone rather than boundstone with only a few horizons of stromatolites and no large-scale reefs. Stromatolite reefs are present at the Spitskop-Swartkloofberg contact, but have substantially lower vertical relief (<5 m) than in section NNw (fig. 7A). The dominant morphologies of these stromatolites are large, onion-like domes (fig. 7B–C). As in the western fault block, these reefs are onlapped by silty limestone and siltstone that contains carbonate olistoliths reaching sizes up to 10s of meters in length and several meters in thickness (figs. 7A, 9A, 9D). Overlying this interval of olistostrome and siliciclastic rocks, are thin bedded silty limestone, limestone, and siltstone that contain two beds of low relief stromatolites, as well as an ash bed dated at 538.04 ± 0.14 Ma (Nelson et al., 2022). Above this, a prominent interval of carbonate sedimentary breccia and olistostrome is found at the base of an upper unit dominated by siliciclastic strata. Within the uppermost exposed strata, above a thin interval of carbonate breccia with sandy matrix (fig. 8B–C), an ash bed was dated at 537.95 ± 0.28 Ma (Nelson et al., 2022). As in section NNw, the lower and upper parts of the Swartkloofberg Formation are siliciclastic dominated, separated by a carbonate-dominated interval, allowing for broad correlations between the sections (fig. 4).

In the easternmost preserved fault block of the upper Schwarzrand Subgroup, section NNe (fig. 10), the precise thickness of the upper Spitskop Member was not measured, but is estimated to be similar to that of NNc. Here, domal stromatolites with <1 m of relief are preserved at the Spitskop-Nomtsas contact (fig. 10B). The lower Swartkloofberg Formation is predominantly thin bedded silty limestone (fig. 9G) with subordinate siltstone, sandstone, and limestone grainstone, as well as two stromatolitic intervals. At the top of this unit there is a well-developed horizon of low-relief (<1 m) stromatolitic patch reefs that is then overlain by an interval dominated by siliciclastic turbidites (fig. 9F). Above these turbidites is a horizon of carbonate olistostrome and breccia that marks a return to dominantly carbonate deposition in the form of thinly bedded grainstone, wackestone, mudstone, and silty limestone with marl to shale partings and thin interbeds. This unit is overlain by a large-scale stromatolite reef complex—with preserved reefs reaching at least 20 m of vertical relief (fig. 11). Reefs include stromatolitic and thrombolitic microbialite textures. Neptunian dikes that are meters in length and decimeters wide cut the reef and are infilled with carbonate cement growing inward from the fissure walls—these commonly display radial fibrous or botryoidal calcite cement, suggesting many of these cements were originally aragonite, and minor dolomite cement (fig. 11D–E). These structures and their infilling cements closely resemble documented neptunian dikes that transect large stromatolite and thrombolite reefs in the c. 548 Ma Zaris Formation of the Kuibis Subgroup in the Zaris Subbasin (Grotzinger et al., 2000). The upper Swartkloofberg reefs are onlapped by siltstone that is preferentially eroded away, leaving primary reef topography. Primary reef edge scarps preserve steeply dipping to sub-vertical microbialite laminations. Tongues of limestone talus breccia comprising reef-derived clasts are preserved adjacent to reef scarps (fig. 11). One ash bed is preserved at the base of this reef complex, and a second is preserved within the reef and was dated in this study using zircon U-Pb CA-ID-TIMS, yielding a date of 537.64 ± 0.25 / 0.34 / 0.67 Ma—the weighted mean of the four youngest of five individual zircon analyses (mean square weighted deviation = 0.68) (figs. 12; figs. SI1B–D). Accordingly, this represents the maximum age for the upper Swartkloofberg Formation.

Within the diamictites of the Swartkloofberg Formation in all of these sections, no clear evidence for glacially influenced depositional processes, such as striated clasts, ice rafted debris, or the presence of exotic clasts, was observed. In Namibia, just south of the C13 road, outcrops of glaciogenic polymictic diamictite of the upper Paleozoic Dwyka Group with features such as striated clasts and local underlying striated pavements directly overlie non-glacial diamictite, breccia, and olistostrome of the Swartkloofberg Formation. As this contact can be locally indistinct, it is imperative that geologists not confuse these separate units when interpreting the depositional environments of the Swartkloofberg Formation.

4.1.2. Chemostratigraphy of the terminal Schwarzrand Subgroup, Neint Nababeep Plateau

Carbon isotope values (δ13C) of carbonates within the lower and middle part of the Swartkloofberg Formation measured in section NNc are mostly ~ +1‰ with scattered (and more negative) values as low as ~ -1‰ (fig. 4). δ13C values of carbonate turbidites in the upper Swartkloofberg Formation in section NNe show significant scatter between -3.9‰ and +1.4‰ with possible oscillatory trends (fig. 4). These data are challenging to interpret, and, while the rapid small-scale oscillations could reflect changes to marine or platformal dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) compositions, the scatter also could result from changing sources for re-deposited carbonate grain allochems with different δ13C compositions. Alternatively, some scatter could result from localized organic carbon remineralization given the mixed carbonate-siliciclastic nature of this unit. Carbonates from the stromatolite reefs overlying this unit have stable δ13C values ~ +1‰, which are likely more representative of platformal DIC values (fig. 4).

4.1.3. Biostratigraphy of the terminal Schwarzrand Subgroup, Neint Nababeep Plateau

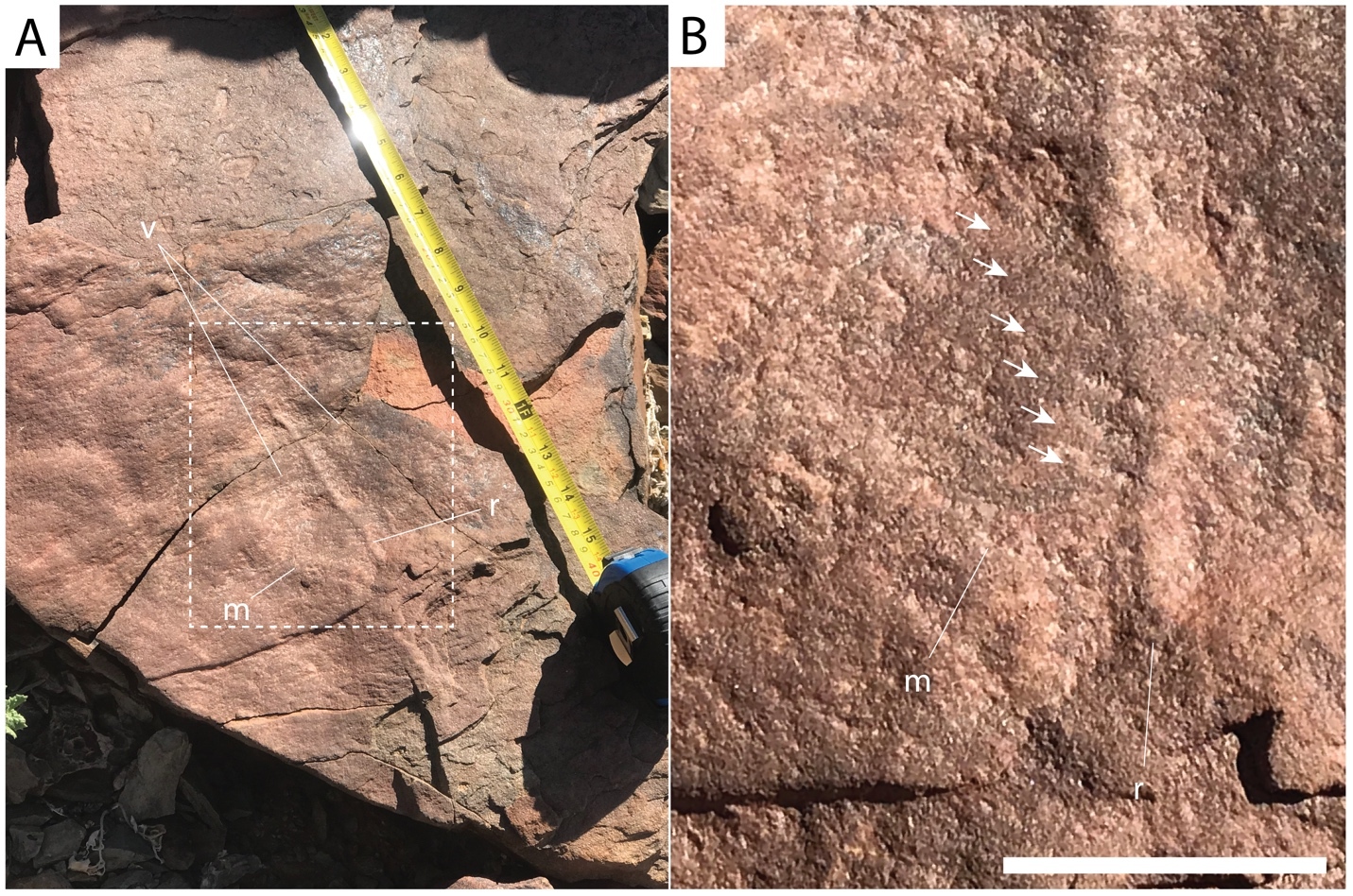

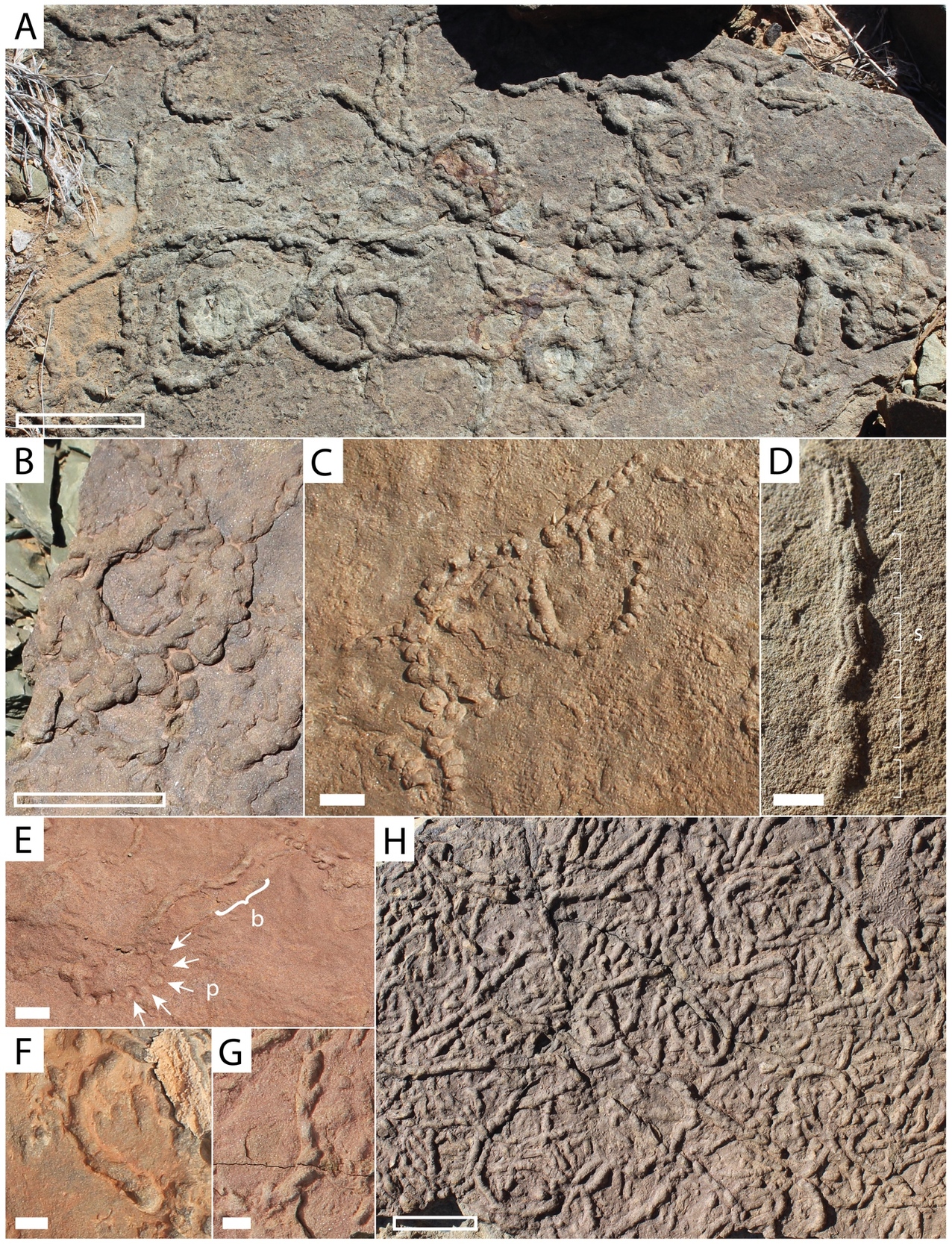

In outcrops of the Neint Nababeep Plateau, strata of the Spitskop Member of the Urusis Formation preserve Ediacaran body fossils including Cloudina, Swartpuntia, and erniettomorphs (Ernietta and/or Pteridinium); trace fossils including Parapsammichnites, Archaeonassa, Helminthopsis, and meiofaunal traces; and scratch circles (fig. 13; Nelson et al., 2022). Calcified tubular shelly fossils and fossil hash occur within packstone and wackestone of the lower Swartkloofberg Formation (fig. 14). These are most commonly recrystallized tubes visible in long or cross section, but in select cases fossils are replaced by iron oxide (likely oxidized from pyrite), and there are some examples that preserve the characteristic funnel-in-funnel morphology of cloudinomorphs (fig. 14B–C). This suggests many of these tubular fossils are poorly preserved Cloudina, although it is possible (and perhaps likely) that there is additional taxonomic diversity among these tubular fossils (see also Turk et al., 2022; Turk, Pulsipher, Bergh, et al., 2024). Trace fossils occur in the lower to middle Swarkloofberg Formation, preserved in both siliciclastic and limestone facies (fig. 15). All identified trace fossils are bed-planar, and three primary morphologies have been identified: 1) simple, bed-planar, unbranched trace fossils with no evidence of overcrossing, which are identified as Helminthopsis (Heer, 1877); 2) large (>1 cm in width), densely spaced and overlapping bed-planar burrows that are unbranched with structureless infill, which are identified as Palaeophycus (Pemberton & Frey, 1982); and, 3) large (>1 cm in width) bi-lobed and unbranched trace fossils with pronounced medial furrows that display looping and overcrossing, which are identified as variants of Psammichnites gigas (Mángano et al., 2022). One cast of a body fossil with prominent subparallel, fanning ridges preserved in fine sandstone in the lower Swartkloofberg Formation is identified as an erniettomorph (fig. 14A; Nelson et al., 2022). This likely represents either Ernietta or Pteridinium based on preservation of a vane constructed of tubular modules, but incomplete preservation of a single vane impedes further classification. In addition, poorly preserved circular structures may represent poorly preserved holdfasts (fig. 15G).

4.2. Farm Swartkloofberg

4.2.1. Lithostratigraphy and geochronology of the terminal Schwarzrand Subgroup, Farm Swartkloofberg

The Swartkloofberg Formation (formerly Nomtsas Formation) is preserved on three separate thrust sheets within this area (Saylor & Grotzinger, 1996). In the eastern-most exposures of the lower thrust sheet on Farm Swartpunt, small hills of Swartkloofberg are inferred to stratigraphically overlie the Spitskop Member, although the contact is covered. The inference, based on adjacent stratigraphy of the Spitskop Member, is that the Swartkloofberg Formation may have cut down through as much as 120 m into the upper Spitskop (Saylor & Grotzinger, 1996). In this study, we did not examine these outcrops in detail due to their lack of stratigraphic context, but they are described as a mix of shale, and matrix- and clast-supported conglomerate (Saylor & Grotzinger, 1996).

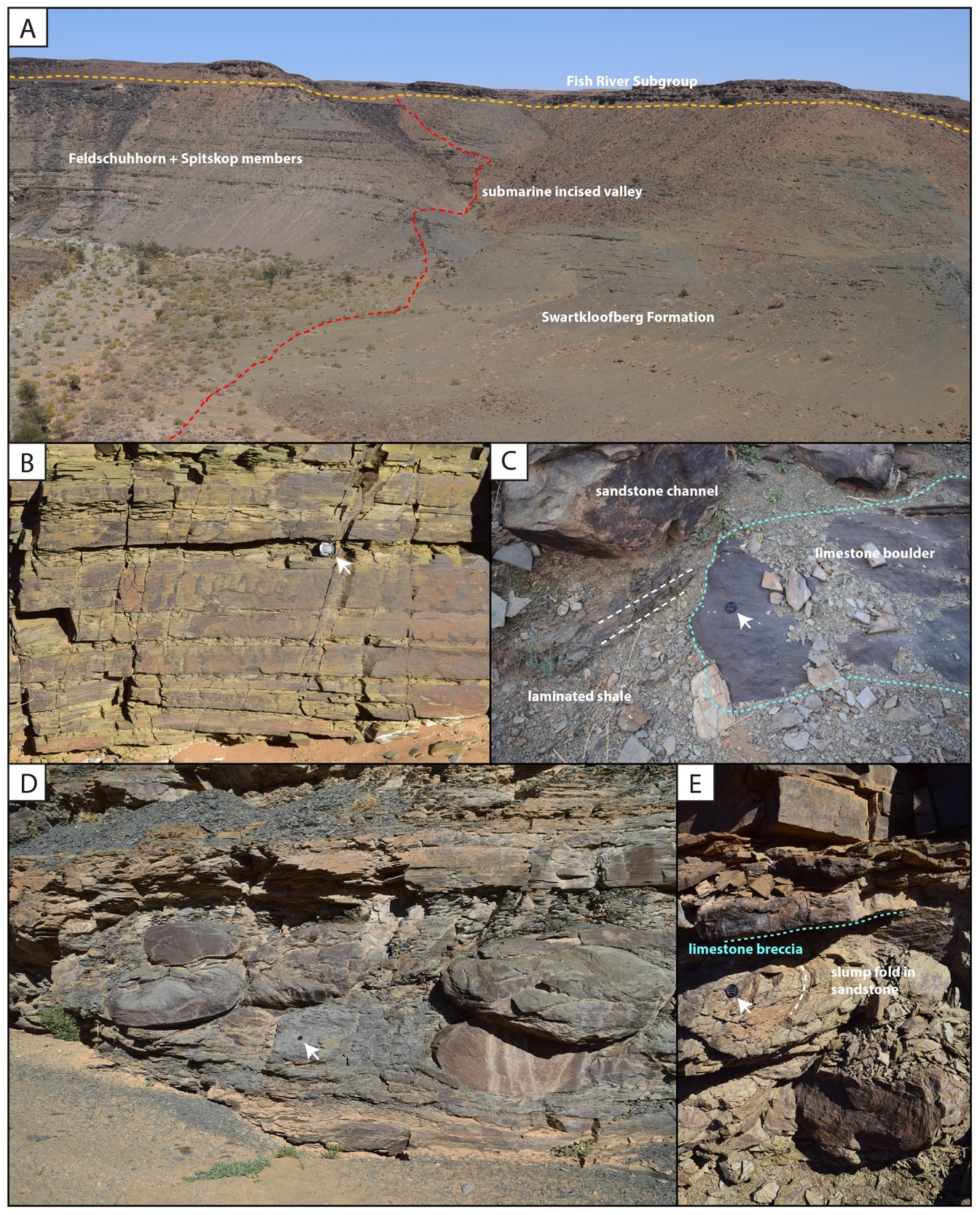

Outcrops of the overlying middle thrust sheet, which contains the most extensive exposures of the Swartkloofberg Formation in this area, were examined in detail where they are preserved within a well-exposed hill on Farm Swartkloofberg (fig. 16). The basal-most outcrops of the underlying Urusis Formation are bedded limestone of the upper Huns Member, which are overlain by high-relief (up to 50 m) stromatolite pinnacle reefs and onlapping green shale to fine sandstone of the Feldschuhhorn Member (fig. 17A–B; Grotzinger & Miller, 2008; Saylor & Grotzinger, 1996). The Feldschuhhorn Member is c. 90 m thick and overlain by silty limestone and grainstone of the basal Spitskop Member. The Spitskop Member here includes two distinct intervals of carbonate separated by an ~16 m interval of shale to very fine sandstone. The base of the siliciclastic interval marks a transgressive surface – not dissimilar from that of the underlying Feldschuhhorn Member – and analogous pinnacle reefs of stromatolites developed at this surface that are locally dolomitized and have vertical reliefs of up to at least 20 m (fig. 17E). The upper carbonate interval is ~30 m of ribbon bedded grainstone to mudstone with beds of mudchip rudstone. These preserve planar bedding and low-angle cross stratification. Above this is an ~10 m interval of stromatolitic dolostone.

Stromatolites of the uppermost Spitskop are overlain by green shale that contains thin patch reefs of stromatolitic limestone within the basal meter. The sharp yet concordant contact defines the base of the Swartkloofberg Formation, which can be followed along strike for ~1 km to the north, along which it is apparently conformable (fig. 16). However, on the southern end of the hill, the base of the Swartkloofberg Formation incises into the upper Spitskop Member forming a steeply walled valley that cuts out the upper carbonate interval and middle siliciclastic interval to the south with up to 50 meters of vertical relief, such that the Swartkloofberg Formation sits directly on bedded carbonate and stromatolitic pinnacle reefs of the lower carbonate interval (figs. 16, 17). This incised valley is infilled by olive green shale to fine sandstone that contains floating clasts of carbonate that range from pebbles to boulders of up to several meters in diameter. Diamictite clasts are primarily limestone and dolostone, matching lithologies of the incised Spitskop Member—many of the larger examples are stromatolitic dolostone (figs. 17D, 18B–D). There are also channel forms of carbonate breccia and channel forms and clasts of medium to coarse micaceous brown sandstone that preserve slump folds. Carbonate clasts and breccia channels are especially common near the edge of the incised valley and adjacent to preserved pinnacle reefs. The upper 20 m of strata infilling the incised valley are characterized by thick channel forms of clast-rich diamictite and carbonate breccia with brown-weathering silt to sand matrix (fig. 18A). Soft-sediment slump folds are preserved beneath channel bases (fig. 18C).

Above the preserved incised valley fill, and where it conformably overlies the upper Spitskop Member, the Swartkloofberg Formation is dominantly shale to fine-grained sandstone with subordinate channels of medium to coarse-grained sandstone, some of which preserve slump folds, channels of carbonate clast diamictite with minor sandstone clasts, and rare floating cobble to boulder-sized clasts of carbonate or carbonate sedimentary breccia (fig. 17F). We identified an ash bed 0.5 m above the base of this unit that we consider equivalent to that dated by Grotzinger et al. (1995) as 538.18 ± 1.11 Ma (Schmitz, 2012 recalculation) based on the stratigraphic column of Saylor and Grotzinger (1996), but our preliminary geochronology attempts generated only detrital zircon dates from this bed (fig. 17H). Approximately 60 m above the base of the unit, a 5-meter stratigraphic interval preserves large olistoliths of limestone and limestone sedimentary breccia that reach at least 10 m in diameter (fig 17F–G). Within this olistolith horizon there are also transported tabular to rounded clasts of silicified volcanic tuff, which were previously sampled and yielded a zircon U-Pb CA-ID-TIMS date of 538.58 ± 0.19 Ma (fig. 17G; Linnemann et al., 2019). The upper 20 m of exposed Swartkloofberg Formation transitions from dominantly siltstone to a succession of siliciclastic turbidites, preserving planar laminated and ripple cross laminated fine to medium-grained micaceous sandstone, interbedded with siltstone and shale, suggestive of Bouma B-E subdivisions (fig. 18F). Bed bases preserve a variety of sole marks, including tool and flute marks, some of which were measured and indicate west-directed paleoflow (fig. 17G–I). The overall coarsening upward trend from dominantly shale to sandstone turbidites suggests a progradational sequence within the Swartkloofberg Formation at this locality, accompanied by migration from more distal to more proximal turbidite facies. Yet, the highest preserved exposures, ~90 m from the basal contact, suggest the depositional environment was still sub-wave base.

In the uppermost preserved thrust sheet, the Spitskop Member is thin (<60 m) and includes intervals of limestone rudstone (platy clasts, intraclast breccia), thin bedded limestone, and shale. This has been interpreted as the most basin-ward exposures of the Spitskop that were deposited on the slope of the Urusis Formation carbonate platform (Saylor & Grotzinger, 1996). Only a few meters of preserved Swartkloofberg Formation remain exposed at the top of a hill within a syncline core, where matrix-supported diamictite, consisting of primarily angular carbonate clasts within light green to light grey shale matrix (fig. 18E), sharply overlies limestone intraclast breccia of the upper Spitskop Member with a channelized base.

4.2.2. Biostratigraphy of the terminal Schwarzrand Subgroup, Farm Swartkloofberg

On adjacent Farm Swartpunt, the well-studied hill of the upper Spitskop Member preserves a rich fossil assemblage that includes the soft-bodied erniettomorph taxa Pteridinium, Ernietta, Nasepia and Swartpuntia, along with Aspidella-type holdfasts (Darroch et al., 2015; Grotzinger et al., 1995; Narbonne et al., 1997), the calcified body fossils Cloudina and Namacalathus (Grotzinger et al., 1995; Linnemann et al., 2019), simple bed-planar ichnotaxa such as Helminthopsis and Helminthoidichnites, meiofaunal traces, and more complex trace fossils including treptichnids (the broader group of serially-probing traces to which T. pedum belongs) and Streptichnus narbonnei (Darroch et al., 2021; Jensen & Runnegar, 2005; Linnemann et al., 2019). On the middle thrust sheet of Farm Swarkloofberg, the middle siliciclastic interval of the Spitskop Member preserves treptichnids in the basal meter, as well as scratch circles indicating the presence of benthic tethered organisms (fig. 19; cf. Jensen et al., 2018). In the overlying Swartkloofberg Formation, one poorly-preserved specimen of an erniettomorph body fossil – tentatively identified as Pteridinium – was found on the top surface of medium- to coarse-grained red sandstone beds, ~30 m above the basal valley fill (fig. 20). These beds form a prominent break in slope and the slab preserving this fossil has been transported a short distance downslope, but was easily re-constructed back to its original position in the outcrop. The upper part of the outcropping Swarkloofberg Formation preserves abundant trace fossils, primarily on the soles of sandstone turbidite beds, that include Helminthoidichnites, Helminthopsis, Gordia, treptichnids, and trace fossils possessing probing-type morphology and an apparent radial organization resembling Streptichnus narbonnei (fig. 21). A possible poorly preserved holdfast structure was also identified in this interval (fig. 21E). Treptichnid trace fossils are preserved on the bases of gutter casts <5 m below and within the turbidite interval (fig. 21F). In this section in particular, the distinction between simpler treptichnid trace fossils and T. pedum is key; treptichnid trace fossils are widely distributed throughout the Schwarzrand Subgroup (Darroch et al., 2021; Jensen et al., 2000; Jensen & Runnegar, 2005; Turk et al., 2022), and thus identification of T. pedum is arguably harder in the Nama Group than in other ECB sections worldwide. In addition, T. pedum is a trace fossil with complex three-dimensional architecture and therefore can be preserved in a number of different styles, depending on where traces are split and exposed in the vertical plane (Wilson et al., 2012). However, despite extensive searching our group found no evidence in the Swartkloofberg section for any of the more complex and systematic offset probing patterns that distinguish T. pedum. As such, we identify these traces as treptichnids (sensu Jensen et al., 2000), noting broad morphological and behavioral similarities with those that have been found in the lower Huns and Spitskop members (e.g., Darroch et al., 2021). Other studies that have stated that T. pedum exists in this section (e.g., Grotzinger et al., 1995; Linnemann et al., 2019) have not figured any specimens of this fossil at this locality. Grotzinger et al. (1995) cite Germs (1972b), who figured specimens similar to those examined in our study (his plate 2, figures 4–6). However, rather than identifying these as unequivocal Treptichnus (or Phycodes) pedum, Germs (1972b) captioned them as “worm tracks” and suggested some of them are “closely related to or identical with Phycodes pedum Seilacher.”

4.3. Farm Sonntagsbrunn

4.3.1. Lithostratigraphy of the terminal Schwarzrand Subgroup, Farm Sonntagsbrunn

Previous focused study of strata of the upper Schwarzrand Subgroup (formerly Nomtsas Formation) on Farm Sonntagsbrunn revealed the presence of two distinct incised valley deposits overlain by a laterally continuous unit of sandstone that forms the local escarpment/canyon rim (fig. 22; Wilson et al., 2012). This farm is located on a tributary of the Fish River Canyon, and down-stream towards the main canyon, limestone of the upper Huns Member of the Urusis Formation is preserved. Green shale of the Feldschuhhorn Member overlie this, and the upper Urusis Formation is siliciclastic-dominated compared to exposures of this unit in the southwestern parts of the Witputs Subbasin, such that the Feldschuhhorn Member makes up most of this interval. There are subordinate thin sandstone beds that are massive or planar laminated, with some preserving low-angle cross-stratification and some preserving slump folds. There are two thin beds (<5 m) of thinly bedded limestone, the upper of which was previously defined as the Spitskop Member (Wilson et al., 2012). However, much of the Feldschuhhorn Member in this area may be a siliciclastic-dominated correlative to the Spitskop Member in the carbonate-dominated depocenter of the Witputs Subbasin to the southwest, given differences in stratigraphic thickness (e.g., fig. 4).

Disconformably overlying the Urusis Formation, the stratigraphically lower incised valleys, “Valley Fill 1” of Wilson et al. (2012), are here considered part of the Swartkloofberg Formation, based on similarities to the previously described Neint Nababeep Plateau and Farm Swartkloofberg localities. The incised valleys that reach up to at least 60 m in vertical relief are infilled by laminated shale with subordinate sandstone beds and channel forms interpreted as turbidites and mass transport deposits that preserve examples of normal grading, ripple cross laminations, and soft-sediment deformation (fig. 23). This unit also contains channel forms of carbonate-clast breccia, with clasts derived from limestone of the Spitskop Member, in addition to some floating clasts of limestone (fig. 23C, 23E). There is also at least one example of a large rotated limestone block within the valley fill that is interpreted as an olistolith derived from the Spitskop Member (Wilson et al., 2012). All of the incised valley infill is interpreted as having been deposited below wave base with suspension dominated sedimentation, interrupted by episodic sand-laden density flows and carbonate-debris flows derived from canyon walls or updip carbonate strata. There is no clear progradational trend within the valley fill of the Swartkloofberg Formation at this locality (Wilson et al., 2012). Thus, these lower valleys infilled by the Swartkloofberg Formation are most easily interpreted as submarine canyons incised into the shelf by mass wasting and headwall erosion (Wilson et al., 2012).

Disconformably overlying either the upper Urusis Formation or valley infill strata of the Swartkloofberg Formation are stratigraphically higher incised valleys, “Valley Fill 2” of Wilson et al. (2012), which reach at least 25 m in vertical relief. Interbedded channelized sandstone and shale near the base of the infilled valleys onlap the valley edges and grade upwards into sandstone (fig. 24). These infilling strata are very distinct from those of the underlying incised valleys based on the prevalence of cross-bedded sandstone (fig. 24A–B). In the lower interval of the infill sequence there are also channelized forms of limestone-clast breccia with micaceous, coarse-grained sand matrix, locally amalgamated with channel forms of coarse to very coarse trough cross-stratified sandstone (fig 24A–B). Within valley infill strata, sandstone beds preserve ripple cross-lamination, interference ripple marks, bifurcating wave-formed ripple marks, trough cross-bedding, and load structures. Intervals of mud-draped thin bedded sandstone (flaser to lenticular bedding) and herringbone cross-stratification suggest tidal-influence (fig. 24C, 24H). These more heterolithic strata grade into an upper sandstone unit that is dominated by medium- to thickly-bedded trough cross-bedded medium- to coarse-grained quartz arenite that also directly caps the Spitskop Member of the Urusis Formation adjacent to preserved incised valleys, forming the modern canyon rim (fig. 24D). While Wilson et al. (2012) referred to this unit as the “upper Nomtsas Formation”, this is the same unit that overlies the Urusis Formation throughout the Fish River Canyon and is regionally mapped as the base of the Stockdale Formation of the Fish River Subgroup (fig. 24E–F). Because there is not a distinct break between this unit and the underlying strata infilling the upper incised valleys at Farm Sonntagsbrunn, we interpret all of these strata formerly included as “Valley Fill 2” and “upper Nomtsas Formation” as part of the basal Stockdale Formation. The more heterolithic strata infilling the incised valleys were deposited in fluvial to intertidal environments, while the more laterally extensive overlying sheets of cross-stratified sandstone in the uppermost exposures of the unit were deposited in upper shoreface environments. Thus, the basal Stockdale Formation is interpreted as a transgressive sequence deposited after exposure of the Urusis Formation and fluvial incision of these upper incised valleys and during subsequent base level rise. This is supported by the presence of karst features and mudcracks at the Spitskop Member-Stockdale Formation contact (fig. 24D–G).

4.3.2. Biostratigraphy of the terminal Schwarzrand Subgroup, Farm Sonntagsbrunn

In sections on Farm Sonntagsbrunn, the Feldschuhhorn Member of the Urusis Formation preserves organic-walled, branching tubes assigned to the probable algal taxon Vendotaenia antiqua (Cohen et al., 2009), as well as simple, bed-planar trace fossils (Helminthopsis, Archaeonassa). At nearby localities along the Fish River Canyon, correlative strata of the upper Feldschuhhorn Member and lower Spitskop Member also preserve the trace fossils Parapsammichnites and treptichnids, as well as tubular body fossils identified as Archaeichnium, but – given recent re-examination of the type material of this genus (Turk, Pulsipher, Bergh, et al., 2024) – more likely represents a different genus of late Ediacaran tubefauna (Buatois et al., 2018; Darroch et al., 2021). Above this, within strata of the Swartkloofberg Formation infilling the lower incised valleys, no trace fossils were identified, although there are sandstone beds preserving abundant kinneyia-type wrinkled surfaces that are interpreted as microbially induced sedimentary structures. Overlying this unit within the upper incised valleys, heterolithic strata infilling the valleys and near the transition from the valley infill to the overlying sheet sandstone preserve abundant trace fossils that are clear examples of the ichnotaxon T. pedum (fig. 25; Germs, 1983; Grotzinger et al., 1995; Wilson et al., 2012), preserved in a wide variety of morphologies on both bed soles and tops (fig. 25; Wilson et al., 2012). While these occurrences of T. pedum have previously been correlated to the strata of the terminal Schwarzrand Subgroup at Farm Swartkloofberg (e.g., Grotzinger et al., 1995), our revised stratigraphic interpretations instead place these fossil occurrences within the basal Fish River Subgroup, as described in section 4.3.1 (fig. 22).

5. Discussion

5.1. Tectonostratigraphic interpretation of the upper Schwarzrand Subgroup, Witputs Subbasin

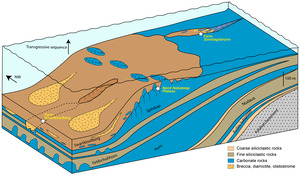

Foreland basins demonstrate consistent trends in sedimentary fill in which they evolve from an underfilled phase (flysch) to an overfilled phase (molasse) (e.g., Catuneanu, 2004; Crampton & Allen, 1995). The underfilled phase, during which dynamic subsidence (driven by the subducting plate) exceeds flexural uplift, typically results in marine, flysch-style sedimentation in which there is more accommodation space generated than sediment deposited. Subsequently, the overfilled phase, during which flexural uplift associated with orogenic loading/unloading exceeds dynamic subsidence, typically results in nonmarine, fluvial-dominated sedimentation (molasse-style of sedimentation) and forms in the waning stages of the foreland basin lifespan, leading to its ultimate demise. This distinction is emphasized because it is a useful framework for interpreting the stratigraphy of the Nama Group: broadly, the Kuibis and Schwarzrand subgroups were deposited within marine shelf and slope environments associated with the underfilled phase of this foreland basin, while the Fish River Subgroup was deposited within fluvio-deltaic environments associated with the overfilled phase (fig. 1).

In the Witputs Subbasin, the Urusis Formation of the Schwarzrand subgroup comprises intercalated intervals of limestone and fine-grained siliciclastic rocks. Intervals of limestone were deposited on a carbonate ramp within highstand systems tracts, while shale, siltstone, and sandstone were deposited mostly below wave base within transgressions and subsequent progradational successions (e.g., Nelson et al., 2022; Saylor, 2003). Within the middle and upper thrust sheets at Farm Swartkloofberg, which represent the most distal preserved exposures of the carbonate shelf, high relief pinnacle-form stromatolite reefs formed at these transgressive surfaces and were eventually drowned by shale, indicating the magnitude of these transgressions exceeded 10s of meters (figs. 16, 17). These sequences may have been externally forced by global climate perturbations, but alternatively may have been principally generated by higher-frequency foreland cycles that were controlled by the delicate balance between accommodation and sedimentation (Saylor, 2003). In such a setting, it is exceedingly difficult to disentangle the contributions that tectonic flexure, dynamic subsidence, sediment supply, and eustasy have on local base level (Catuneanu, 2004). Comparison of facies of the Urusis Formation across the Witputs Subbasin, along with paleocurrent data, suggests the carbonate ramp was deepening to the southwest (Germs, 1983; Saylor, 2003; Saylor & Grotzinger, 1996). This is consistent with deposition in an underfilled foreland basin (based on the prevalence of marine facies) with basin accommodation driven by dynamic subsidence associated with subduction related to the incipient Gariep orogen.

At both the Neint Nababeep Plateau and, locally at Farm Swartkloofberg, the contact between the Spitskop Member of the Urusis Formation and the Swartkloofberg Formation is a concordant, apparently conformable surface in which bedded grainstone of the upper Spitskop is overlain by stromatolitic reefs and onlapping shale and lime mudstone of the basal Swartkloofberg Formation (figs 4, 16). In addition to observations of its geometry and character, the conformable nature of this contact is supported by high precision geochronology which indicates fast sedimentation rates with little time for hiatuses within cryptic paraconformities (Nelson et al., 2022). This surface is interpreted as a major transgression as indicated by a transition from shelf carbonate sedimentation to sediments primarily deposited below wave base in slope environments. Stromatolite reefs in the lower Swarkloofberg Formation were presumably formed by photosynthetic cyanobacteria fighting to keep pace with increasing subsidence, which were eventually drowned out by increasing terrigenous sediment and/or water depth. Overlying strata are dominated by shale and ribbon-bedded silty limestone with intervals of olistostrome, channelized carbonate breccia and diamictite, slumped sandstone channels, and turbidites. These facies are suggestive of deposition on a high-gradient slope (fig. 26). Within intervals of diamictite, all clasts are local in origin, resembling lithologies of the Urusis and Swartkloofberg formations; there is no evidence of glacial influence, such as lamination-penetrating dropstones, till pellets, or striated clasts. Indeed, the olistoliths and clasts are within channelized bodies with massive mudstone matrix, suggesting they were deposited as gravitationally-transported slurries, consistent with marine slope settings (Saylor & Grotzinger, 1996).

We interpret this transgression and transition from shelf to slope environments at the Urusis-Swartkloofberg contact to reflect increased downward flexure of underlying continental crust, resulting from an approaching orogenic load, which became a more important influence on local basin accommodation than regional dynamic subsidence (fig. 26). This flexure appears to have been dominantly the result of tectonic loading to the west or southwest on the basis of major E–W oriented facies change across fault blocks on the Neint Nababeep Plateau, which can be correlated using distinctive silicified tuff beds and detailed lithostratigraphy (figs. 4, SI1A). Within the western fault block, pinnacle reefs of the basal Swartkloofberg Formation reach 10s of meters of relief (fig. 6), while in the central fault block this same interval is dominantly bedded grainstone with stromatolite bioherms near the top reaching < 5 m of relief (fig. 7). In the eastern fault block, correlative bioherms are < 1 m in relief (fig 10). Morphologies of individual stromatolites within this interval are also distinct from west to east: to the west, high-relief, conical stromatolites are common (fig. 6F), while the eastern fault block is dominated by low-relief onion-like domal stromatolites with thrombolitic cores (fig. 7). The observed differences in reef morphology and size across ~6 km of lateral exposure suggest that more accommodation space was generated to the west (or southwest, given outcrop constraints) relative to the east (or northeast) at isochronous horizons (figs. 4, 26). The eastern section also contains more ribbon-bedded silty limestone and more sandstone turbidites relative to the western sections, which have more shale, olistostrome, and diamictite. This is overall consistent with more distal depositional settings and more over-steepened slopes to the west. High-relief (up to 20 m) stromatolite reefs are preserved in the uppermost exposures of the Swartkloofberg Formation in the eastern fault block, which may reflect eastward migration of craton flexure (figs. 10, 11). Unfortunately, it is more difficult to ascertain paleoenvironmental deepening trends in the Swartkloofberg Formation at Farm Swartkloofberg, as broadly exposed strata are confined to a small area on a single fault block (fig. 16; Saylor & Grotzinger, 1996).

The incised valleys that cut into the Spitskop and Feldschuhhorn members, and which are infilled by the Swartkloofberg Formation at Farm Swartkloofberg and Farm Sonntagsbrunn, are interpreted as submarine canyons (Nelson et al., 2022; Saylor & Grotzinger, 1996; Wilson et al., 2012). These steep-walled canyons were infilled by a combination of suspension-dominated sedimentation comprising mud and gravity-driven mass flow deposits of sand, breccia, diamictite, and olistoliths derived from up-dip localities and/or canyon walls (figs. 17, 18, 23). There is no evidence of fluvial incision or deposition within these canyons. Instead, these canyons were generated by headward erosion and propagation of submarine channels formed via mass wasting, with slope instability driven by eastward migration of craton-flexure, also consistent with eastward migration of high-relief stromatolite reefs (fig. 26). While existing exposures limit the ability to analyze canyon geometries, mappable canyon walls have broadly E–W orientations (figs. 16, 22). The westward orientation of facies patterns and submarine canyons in the Swartkloofberg Formation suggests that the sharp increase in flexure during deposition was primarily related to tectonic loading associated with the Gariep Orogen. The transition from the Urusis to the Swartkloofberg Formation thus reflects a transition from the basin responding to distal effects of dynamic subsidence of Gariep-associated subduction, to proximal tectonic loading as the orogen front approached.

With the progression of the Gariep and Damara orogens, flexural uplift associated with the approaching fold and thrust belts and/or orogenic unloading resulted in the evolution of the Nama foreland basin from an underfilled phase to an overfilled phase, manifested by the deposition of the Fish River Subgroup. The upper incised valleys at Farm Sonntagsbrunn (“Nomtsas VF2” of Wilson et al., 2012) are infilled by fluvial and peritidal sediments (here interpreted as the basal Stockdale Formation of the Fish River Subgroup), suggesting that they formed as the result of exposure and fluvial incision. This interpreted depositional setting contrasts with the interpreted depositional setting and paleo-water depth of the underlying submarine-generated valleys infilled by the Swartkloofberg Formation. This interpretation is corroborated by evidence of a widespread exposure surface adjacent to the upper incised valleys and throughout the Fish River Canyon region at the Spitskop Member-Stockdale Formation contact, evidenced by development of karst dissolution and hardgrounds at this surface, the presence of mudcracks, and deposition of overlying peritidal strata (fig. 24). Thus, at least in the Witputs Subbasin, there is clear evidence for an unconformity at the base of the Fish River Subgroup. The duration of this depositional hiatus remains largely unconstrained; while no tuff horizons have been described within the Fish River Subgroup, the youngest reported detrital zircon ages of the Stockdale Formation are 531 ± 9 Ma (Blanco et al., 2011).

Following the development of this unconformity and fluvial incision of the upper Schwarzrand Subgroup, the lower Stockdale Formation was deposited within a transgressive sequence with fluvial to intertidal heterolithic facies infilling channels and transitioning up-section into upper shoreface cross-bedded sandstone (fig. 24). While stratigraphic analysis of the overlying Fish River Subgroup is outside of the scope of this study, depositional sequences of fluvial to deltaic siliciclastic facies are consistent with continued deposition within the overfilled, molasse phase of the Nama foreland (Germs, 1983; Geyer, 2005). Paleocurrent data within the Fish River Subgroup suggest sediment primarily was derived from denuding highlands to the north and west, likely associated with mountain belts of the Damara and Gariep orogens, respectively (Germs, 1983). Ediacaran–Cambrian detrital zircons within these molasse deposits were likely sourced from the exhumed Arachania Arc to the west and unroofing granitoids of the Damara Orogen to the north (Blanco et al., 2011). Ultimately, sedimentation surpassed flexural subsidence across the region, resulting in the termination of the Nama foreland basin.

The channelized unconformities at Farm Sonntagsbrunn have previously been used as evidence for an E–W striking forebulge, the “Koedoelaagte Arch”, that was suggested to separate the Witputs Subbasin from a distinct Vioolsdrif Basin, which includes outcrops of the Nama Group in southernmost Namibia along the Orange River and in northwestern South Africa, during Schwarzrand deposition (Germs & Gresse, 1991; Gresse & Germs, 1993). While we agree foreland-related flexure contributed to the formation of these channels (see previous paragraph), we find no evidence for an E–W striking paleotopographic high separating the Witputs and Vioolsdrif regions during deposition of the Schwarzrand subgroup. Combined, the absence of evidence for this paleotopographic arch and the similar lithostratigraphy of the Schwarzrand subgroup between the Witputs and Vioolsdrif areas (e.g., Nelson et al., 2022), lead us to suggest these regions were part of the same basin during Schwarzrand time (c. 545.3 to 537.6 Ma) and that the name, “Vioolsdrif Basin/Subbasin”, should be abandoned. Apparent separation of these outcrop belts is the result of exposure of a broad E–W trending structural window of basement, with overlying strata eroded, rather than a syn-depositional topographic high (fig. 1).

5.2. Nomenclature of the upper Schwarzrand Subgroup, Nama Group

As indicated previously in the Results and Discussion sections, we suggest nomenclature revision of the terminal Schwarzrand Subgroup of the Nama Group. First, we propose that units previously referred to as the Nomtsas Formation in the Witputs Subbasin at localities at Farm Swartkloofberg, Farm Swartpunt, Farm Sonntagsbrunn, and the Neint Nababeep Plateau (Germs, 1983; Nelson et al., 2022; Saylor & Grotzinger, 1996; Wilson et al., 2012) should be a distinct unit that we introduce as the Swartkloofberg Formation (figs. 1, 2). For formalization of this unit, we suggest the type area should be the well-exposed sections on Farm Swartkloofberg in the vicinity of [27.444° S, 16.560° E] (table 1; fig. 16), although there is no exposed top to the unit here. In the vicinity of the Neint Nababeep Plateau, the upper contact is also either not exposed or unconformably overlain by the Carboniferous Dwyka Group (figs. 3, 4). In the vicinity of Farm Sonntagsbrunn, there are exposed lower contacts with the Urusis Formation and upper contacts with the Stockdale Formation, but here, the unit is restricted to paleo-incised valleys, so it is not an ideal type section (fig. 22). We suggest the Swartkloofberg Formation should be included within the Schwarzrand Subgroup, given locally conformable relationships with the Spitskop Member of the Urusis Formation at the Neint Nababeep Plateau and Farm Swartkloofberg. Furthermore, it is interpreted to be genetically related to the Urusis Formation, deposited in the earlier, underfilled stage of the Nama foreland basin, as part of marine flysch deposition. Further investigation and detailed documentation of the Schwarzrand Subgroup-Fish River Subgroup contact in the Witputs Subbasin could reveal additional preserved exposures of this unit, beyond those described in this work. In summary, exposures that were previously mapped as the Nomtsas Formation within the Witputs Subbasin should instead be included in the newly defined Swartkloofberg Formation, the terminal unit of the Schwarzrand Subgroup within the Witputs Subbasin (table 1; fig. 2).

As discussed in section 2.0 (Geologic Background), the type area of the Nomtsas Formation is at Farm Nomtsas in the Zaris Subbasin, >250 km to the north of the localities documented in this study. In the vicinity of Farm Nomtsas, the Kreyrivier, Niep, and Vergesig members, which are readily distinguishable in aerial imagery, comprise dominantly red-bed siliciclastic facies similar to the units of the overlying Fish River Subgroup (fig. 27A). All of these members preserve evidence of shallow, fluvial-deltaic depositional environments, such as raindrop impressions, mudcracks, ripple marks, and trough cross-bedding (fig. 27; Germs, 1983). Trough cross-bedded sandstone in the Niep and Vergesig members indicate largely north to south directed paleocurrents (Germs, 1983), which are inconsistent with dominantly west directed paleocurrents of the underlying Schwarzrand Subgroup but similar to intervals of the Fish River Formation, such as the Breckhorn Formation and Rosenhof Member (Germs, 1983). The facies and paleocurrents of the Nomtsas Formation in the Zaris Subbasin suggest sediments were derived from uplifted highlands associated with the Damara Orogen to the north, akin to provenance of Fish River Subgroup sediments. The Nomtsas Formation strata in the Zaris Subbasin are thus interpreted as the initial molasse deposits, associated with the later, overfilled stage of the Nama foreland, distinct from the marine deposits of the Schwarzrand Subgroup. As such, the Nomtsas Formation in the Zaris Subbasin bears far more similarities in lithologies, depositional environments, and tectonic setting to the overlying Fish River Subgroup than to the underlying Schwarzrand Subgroup, and, accordingly, we suggest that it is reassigned as the basal formation of the Fish River Subgroup in this area.

5.3. The Ediacaran–Cambrian boundary in the Nama Group

The Nama Group provides an important stratigraphic record for global understanding of the nature and timing of the Ediacaran–Cambrian transition. The local Ediacaran–Cambrian boundary has long been placed at the basal contact of the Nomtsas Formation. This placement was based on correlation between the incised valleys preserving T. pedum at Farm Sonntagsbrunn (formerly “Nomtsas VF2” of Wilson et al., 2012, here reinterpreted as basal Fish River) and the incised valleys at Farm Swartkloofberg (Germs, 1983; Grotzinger et al., 1995). Thus, an ash bed dated to 538.18 ± 1.11 Ma with U-Pb air abrasion ID-TIMS of zircon from strata just above the incised valley fill at Farm Swartkloofberg (Grotzinger et al., 1995; Saylor & Grotzinger, 1996; Schmitz, 2012) has been used as a firm minimum age constraint for the appearance of T. pedum, and thus the Ediacaran–Cambrian boundary both locally and globally.

More recently, Linnemann et al. (2019) dated a number of ash beds in the upper Spitskop Member at the neighboring Farm Swartpunt with CA-ID-TIMS, reporting an age from the highest and youngest of these as 538.99 ± 0.21 Ma. They also dated an ash bed at Farm Swartkloofberg from the unit overlying the incised valley (previously Nomtsas Formation, here renamed Swartkloofberg Formation) as 538.58 ± 0.19 Ma. Linnemann et al. (2019) describe this ash bed as “ripped into metre-sized fragments” yet interpret it as a primary ash bed that fragmented during deposition. In the same manuscript, they report Treptichnus cf. pedum, from uppermost strata of the Spitskop Member, and thus interpret the Ediacaran–Cambrian boundary between these two dated ash beds, at c. 538.8 Ma (Linnemann et al., 2019). The identification of T. pedum at Swartpunt has been disputed by subsequent studies (Darroch et al., 2021); despite this, however, 538.8 Ma has become widely used as the Ediacaran–Cambrian boundary age on geologic timescales (e.g., Peng et al., 2020). In contrast, as first proposed by Nelson et al. (2022), the detailed sedimentological and stratigraphic evidence presented here demonstrate that the lowest documented stratigraphic occurrences of the index ichnofossil T. pedum are within the basal Fish River Subgroup at Farm Sonntagsbrunn, rather than the upper Schwarzrand Subgroup.

As described in section 4.2.2., none of the trace fossils reported from either the Spitskop Member or Swartkloofberg Formation can be classified as the ichnotaxon T. pedum. Instead these are examples of the complex, radiating trace fossil Streptichnus narboneii (Jensen & Runnegar, 2005) [cf. fig. 4d of Linnemann et al. (2019)] or treptichnids [cf. plate 2, fig. 5 of Germs (1972b)], which lack the systematic branching pattern of the index ichnotaxon T. pedum, and which first occur much lower in strata of the basal Urusis Formation (Jensen et al., 2000; Turk et al., 2022) that is c. 541–540 Ma (Nelson et al., 2022). Instead, the lowest stratigraphic occurrences of T. pedum that have been documented thus far in the Nama Group are within strata at Farm Sonntagsbrunn that are here interpreted as the basal Stockdale Formation of the Fish River Subgroup (figs. 25, 28). To reiterate, these strata are not correlative to the Swartkloofberg Formation and rather were deposited above a subaerial unconformity in a distinct phase of the Nama foreland basin (molasse, rather than flysch sedimentation). We again concede that – given both the abundance of treptichnids throughout the Schwarzrand Subgroup, and the apparent gradational nature of behavioral complexity exhibited in fossils attributed to this ichnogenus (a likely consequence of the expanded nature of the stratigraphic column preserved in the Nama Group – see below) – distinguishing T. pedum from other treptichnid trace fossils is not trivial and requires a large sample size in order to make confident assignments. However, thus far we have not identified T. pedum in the Swartkloofberg Formation where is preserved on either Farm Swartkloofberg or the Neint Nababeep Plateau, and therefore, the many published high-precision U-Pb dates of ashes from the Urusis and Swartkloofberg formations (Linnemann et al., 2019; Nelson et al., 2022) can only be used as maximum constraints for the first appearance of T. pedum, and the Ediacaran–Cambrian boundary as defined in this manner.

Based on three published and one new high-precision ash bed dates from the Neint Nababeep Plateau, deposition of the Swartkloofberg Formation ranged from 538.56 ± 0.093 Ma to <537.64 ± 0.25 Ma Ma (figs. 4, 12; Nelson et al., 2022; this study). There are two published dates from ash beds in the Swartkloofberg Formation at Farm Swartkloofberg (Grotzinger et al., 1995; Linnemann et al., 2019). The bed dated by Grotzinger et al. (1995) appears to occur outside of the incised valley in the basal Swartkloofberg Formation based on the description and stratigraphic column of Saylor and Grotzinger (1996). Our observations suggest this is an in situ ash-bed just above the Spitskop-Swatkloofberg contact (fig. 17H). Although the zircons were dated by air abrasion ID-TIMS analyses, prior to the development of chemical abrasion and the EARTHTIME isotopic tracer (S. A. Bowring et al., 2005; Condon et al., 2015; Mattinson, 2005), the 538.18 ± 1.11 Ma date of this ash bed recalculated by Schmitz (2012) is within error of the lower Swarkloofberg dates from the Neint Nababeep Plateau (Nelson et al., 2022). The ash bed dated by Linnemann et al. (2019) at 538.58 ± 0.19 Ma, which is ~64 m above the base of the unit, is here interpreted as an olistolith, both based on the sedimentology and geochronology (fig. 17G). The sampled block is internally deformed such that laminations are folded over and discordant with the overall bedding of the unit; there are a number of broken up blocks of silicified ash within the same 5-meter stratigraphic interval of olistostrome that also contain megaclasts of limestone and limestone breccia (fig. 17F–G). These olistoliths were transported from up-dip localities within a gravitational mass-flow deposit, and thus this date should be interpreted as a maximum depositional age. The 538.58 ± 0.19 Ma date closely matches the dated ash bed at the Spitskop-Swartkloofberg contact at the Neint Nababeep Plateau (Nelson et al., 2022), so this could plausibly be a transported block derived from the same ash bed. Taken together, all existing data indicate deposition of the Swartkloofberg Formation continued until after 537.64 Ma. Subsequently, deposited strata of the Nama foreland basin were uplifted, subaerially exposed, and fluvially incised prior to deposition of the basal Stockdale Formation during ensuing marine transgression. As these shallow marine strata of the Stockdale Formation contain the lowest documented occurrences of T. pedum, the first appearance of this ichnotaxon in the Nama Group can be constrained to significantly postdate 537.64 Ma (fig. 28).

In carbonate-rich localities globally, a large negative carbon isotope excursion – the BACE (BAsal Cambrian Excursion) – has been found to immediately predate the first occurrence of T. pedum and/or broadly coincide with other biostratigraphic indicators of the Ediacaran–Cambrian boundary (e.g., Corsetti & Hagadorn, 2003). Limestones within the upper Urusis Formation and lower Swartkloofberg Formation have consistent positive carbon isotope values, suggesting they were deposited prior to onset of this excursion, which thus must have postdated 538.04 ± 0.14 Ma (figs. 1, 4, 28). The uppermost documented carbonate strata of the Swartkloofberg Formation in the easternmost fault block on the Neint Nababeep Plateau (c. 537.64 ± 0.25 Ma) have scattered δ13C values between -3.9‰ and +1.4‰ with possible small-scale oscillatory trends (figs. 4, 28), which prevents confident interpretation of a well-defined negative carbon isotope excursion (cf. BACE). Since this unit comprises ribbon-bedded limestone, thinly interbedded with silty limestone and shale, these scattered δ13C data could reflect: 1) rapid oscillations in marine DIC composition, 2) changing sources of redeposited carbonate grain allochems with different δ13C compositions, or 3) localized organic carbon remineralization. The transition from slope-facies limestone to overlying stromatolite reefs coincides with a transition to stable δ13C values of ~ +1‰, suggesting negative values in the ribbon-bedded limestones may not reliably record marine DIC values, and their chemostratigraphy should be utilized with caution (fig. 4). If these fluctuations reflect marine carbon cycle instability, the observed trends are not readily correlated to the magnitude and structure of the BACE, but may reflect onset of the high frequency carbon isotope variability characteristic of the Ediacaran–Cambrian transition (cf. Maloof et al., 2010; Nelson et al., 2023).

In sum, interpretation of a chronostratigraphically defined Ediacaran–Cambrian boundary at 538.8 Ma within the Nama Group (e.g., Linnemann et al., 2019; Peng et al., 2020) is rejected based on currently available data. The oldest geochronologically constrained first occurrence of T. pedum is c. 533 Ma (Nelson et al., 2023), and onset of the BACE apparently postdated c. 538 Ma but lacks further constraints (fig. 28).

5.4. Increased biological complexity in the terminal Ediacaran

Despite the likelihood that the Ediacaran–Cambrian boundary – as currently defined with biostratigraphy and chemostratigraphy – is positioned at the hiatus between the Schwarzrand and Fish River subgroups, and thus not recorded in the Nama foreland basin due to the regional unconformity, the upper Schwarzrand Subgroup nonetheless preserves a critical, high-resolution record of the origination of Phanerozoic-style infaunal behavior by marine invertebrates in the latest Ediacaran. Deposition of the Urusis and Swartkloofberg formations within the underfilled stage of foreland basin, driven by dynamic subsidence and tectonic loading, provide a sedimentary record in which average sediment accumulation rates exceeded 50 cm/kyr (Nelson et al., 2022). As a result of these high sedimentation rates accompanied by geochronological calibration (Gong et al., 2025; Nelson et al., 2022), these strata offer exceptional resolution into the transforming ecologies of terminal Ediacaran marine environments.

Ediacaran macrofauna, including representatives from the erniettomorph and cloudinomorph morphoclades, are present in the Kuibis Subgroup (c. 548 Ma; S. A. Bowring et al., 2007) and through the lower Swartkloofberg Formation (<538.5 Ma; Nelson et al., 2022). Small plug-shaped burrows, identified as Bergaueria or Conichnus and attributed to broadly sessile organisms, first occur in the Kuibis Subgroup, and are found in siliciclastic units throughout the overlying Schwarzrand Subgroup. Although morphologically simple, chevron-style infill found within some of these burrows suggest a form of escape structure (‘equilibrichnia’), and thus likely were made by organisms possessing muscles (putatively actinian cnidarians; see Darroch et al., 2016, 2021). The stratigraphically lowest trace fossils made by motile, bilaterian invertebrates that have been documented from the Nama Group occur in the lower Urusis Formation within the Nasep Member and the transitional contact to the overlying Huns Member, c. 541–540 Ma (e.g., Darroch et al., 2021; Gong et al., 2025; Jensen et al., 2000; Nelson et al., 2022; Turk et al., 2022). In the Witputs Subbasin, the lack of ichnofossils in the Vingerbreek Member of the Nudaus Formation may be related to its deeper water facies comprising fine-grained siliciclastic rocks deposited dominantly below wave base. If late Ediacaran oceans had relatively low oxygen levels and stratified redox gradients (as often hypothesized; see, e.g., Sperling et al., 2015; Stockey et al., 2024; Tostevin et al., 2019), it is plausible that benthic environments of the Vingerbreek Member could not support motile invertebrate metabolisms. This is perhaps supported by the presence of both trace and body fossils in the Vingerbreek Member north of the Osis Arch, where it contains thicker sandstone beds and may have been deposited in more proximal environments (Darroch et al., 2016, 2021). However, it should also be highlighted that chronostratigraphic correlation of this unit between the Zaris and Witputs subbasins remains uncertain. Regardless, the absence of preserved bilaterian ichnofossils in the shallow marine strata of the Kuibis Subgroup and Niederhagen Member of the Nudaus Formation likely represents primary evolutionary trends rather than environmental biases, as these units show abundant evidence of wave and tidal action. This suggests motile invertebrate bilaterians were uncommon, if at all present, in shallow marine environments prior to 545 Ma, based on the age of the basal Vingerbreek Member (fig. 28; Nelson et al., 2022).

The first appearance of bilaterian trace fossils at the Nasep-Huns transition demonstrates a diverse and complex range of morphologies, including treptichnids, Archaeonassa, Gordia, Helminthoidichnites, Helminthopsis, Torrowangea, and meiofaunal traces (fig. 28; Darroch et al., 2021; Jensen et al., 2000; Turk et al., 2022). These co-occurrences of both bed-parallel and shallow bed-penetrating burrows with a variety of sizes and patterns are suggestive of rapid behavioral evolution among bilaterian invertebrates between c. 545–540 Ma (fig. 28). These occurrences may correspond with specific paleoenvironments and sea-level fluctuations that were linked to local oxygen maxima (e.g., Turk et al., 2022). Further increases in behavioral complexity by c. 539 Ma are evidenced by the appearances of the trace fossils Parapsammichnites and Streptichnus in strata belonging to the Spitskop Member, which represent the first occurrences of sediment bulldozing and active backfilling, therefore illustrating increasingly organized and systematic behavior with more substantial ecosystem engineering impacts (figs. 13, 19, 28; Buatois et al., 2018; Darroch et al., 2021; Jensen & Runnegar, 2005; Nelson et al., 2022). The <538.5 Ma Swartkloofberg Formation also contains bed planar and shallow bed-penetrative burrows, but with notable increases in size: e.g., >1 cm diameter overlapping densely spaced bed-planar burrows on the Neint Nababeep Plateau identified as Palaeophycus (fig. 15; Nelson et al., 2022) and larger bed-penetrating treptichnids identified at Farm Swartkloofberg (fig. 21). At Farm Swartkloofberg, abundant examples of Helminthoidichnites, Helminthopsis, Gordia, treptichnids, and Streptichnus preserved on the soles of turbidite beds demonstrate the existence of diverse bilaterian communities in slope environments, suggesting these groups were not restricted to shallow shelves.