1. INTRODUCTION

Recent research has demonstrated the utility of using Hg anomalies in crustal sediments as proxies for volcanic activity associated with large igneous province (LIP) events, and as proxies for the major extinction events such as those at the Permian–Triassic (PTB) and Cretaceous–Paleogene (K/Pg) boundaries (Bergquist, 2017; Grasby et al., 2017, 2019; Percival et al., 2021; Sial et al., 2016, 2020; Thibodeau et al., 2016). Many Hg anomalies are also closely associated with the timing of globally elevated levels of atmospheric CO2 that resulted in environmental conditions favorable for the generation and preservation of algal and planktonic blooms, resulting in regions of anoxia in the global oceans (Jenkyns, 2010; Jones et al., 2019; Schlanger & Jenkyns, 1976). Such reducing conditions were favorable for the preservation of organic matter in the geologic record and it is these episodes in Earth history that gave rise to some of the most prolific organic-rich hydrocarbon source rocks on the planet (Bergman et al., 2021). These organic-rich source rocks formed in marine and terrestrial environments in which both organic matter and Hg were preserved (Jenkyns, 2010; Schlanger & Jenkyns, 1976; Yao et al., 2022).

Numerous attempts have been made to correlate formation ages for many of the most important organic-rich source rock forming events with the timing of LIPs e.g., Sial et al. (2016, 2020); Grasby et al. (2019), and Bergman et al. (2021). The correlations provide strong evidence for the LIP events initiating globally significant source rock deposition. However, the relationship between the timing of many of the LIP events with specific extinction events is less clear, and continues to be the topic of ongoing research e.g., Sial et al. (2020).

Cinnabar (HgS), is the dominant ore mineral of Hg in Earth’s crust. Mercury isotopes provide compelling evidence for a genetic association of Hg in cinnabar deposits being sourced from sediments deposited during global LIP events. HgS deposits in the Terlingua mining district of SW Texas, and the New Idria Hg mine in the California Coast Range are examples of Hg recycling from organic-rich marls and tuffaceous black shales of Cenomanian–Turonian age (~94.1 Ma; Eldrett et al., 2015), having a Hg isotopic signature confirming a genetic relationship to the OAE-2 LIP event. It was also shown that Hg isotopes in cinnabar ores were enriched in 202Hg, consistent with the δ202Hg isotopic composition of their sediment source (Bryndzia, 2023; fig. 1).

Hydrocarbons play a vital role in the formation of cinnabar ores, with hydrocarbon liquids being the principal ore-forming fluid that transports Hg as Hg0(org) from reduced, organic-rich source rocks and Hg-enriched sediments to the site of mineral deposition. As a generalization, it is the oxidation of reduced Hg0- and H2S-bearing ore-forming fluids that results in cinnabar deposition (Bryndzia, 2023; Bryndzia et al., 2023; Krupp, 1988).

All of the major cinnabar deposits in table 1 are intimately associated with organic-rich rocks, including carbonaceous black shales, limestone/marls, and claystones (the latter derived from altered tuffaceous material), and both liquid and solid hydrocarbons. Many of the claystones are also significantly enriched in Hg, beyond normal crustal abundances (~62.4 ppb; Grasby et al., 2019). They all preserve evidence for being hydrothermally modified during the cinnabar ore-forming process, mostly driven by heat from proximal volcanic and/or igneous activity. It is appropriate, therefore, to discuss the Hg isotope systematics of hydrocarbons, source rocks and Hg-rich sediments in order to better understand how the largest deposits of cinnabar on Earth formed.

The hypothesis being developed in this paper is that most of the Hg in the world’s largest deposits of cinnabar (HgS) was derived from an upper mantle source, similar in Hg isotopic composition to that of CFBs (Yin et al., 2022), and then subsequently remobilized from organic rich source rock sediments by expelled hydrocarbon and reduced formation brines. Mantle derived Hg0 is ejected with volcanic ash into the Earth’s atmosphere, where it undergoes rapid oxidation of Hg0(g) to Hg2+. Much of this oxidized Hg2+ is bound in sediments, both marine and terrestrial, as an alteration product of the very fine-grained ash material. An excellent example of this are the tephra deposits from the Grane oil field in the North Sea, closely associated with claystones and shales throughout the North Atlantic Igneous Province (NAIP). Some of the tuff layers are significantly enriched in Hg, containing up to 17,400 ppb Hg, attributed by Jones et al. (2019) to their close proximity to the source of volcanism.

This paper includes new data on hydrocarbons and source rocks, integrated with previously published Hg isotope data from Hg-enriched sediments, many of which appear to be chronostratigraphically associated with LIPs, and some of the largest Hg ore deposits on Earth (table 1). Mercury isotopes are used to elucidate the processes involving Hg and its subsequent concentration and isotopic enrichment in 202Hg during thermal maturation of organic matter in source rocks and Hg-enriched sediments, and ultimately in cinnabar ores. MDF and MIF fractionation for Hg isotopes is also discussed, together with Hg isotope data for the cinnabar deposits shown in table 1.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Cinnabar deposits

The Hg ore deposits in table 1 range in age from Cambrian to Miocene, and are hosted in a diverse suite of sediments and sedimentary rocks that include organic-rich claystone and alkaline lake sediments in the Miocene-age McDermitt caldera in Nevada (USA), Lower Cretaceous limestones, shales and marls (SW Texas and Peru), altered serpentinite, sandstone and shale (New Idria, CA Coast Range), sandstones, dolomite, and carbonaceous black shale (Permian–Triassic in Indrija, Slovenia), quartzite (Silurian–Devonian in Almaden, Spain), Cambrian-age carbonaceous black shales in Wanshan and Paiting (SW China), and in marls, limestones, calcarenites and sandstones in Monte Amiata (Tuscany, Italy). Hg isotope data for each deposit were compiled from previously published studies, and together with a short summary of the geological setting are given in supplementary tables S2–S8.

2.2. Source rocks and hydrocarbons

Mercury isotope data for source rocks and hydrocarbons consist of previously unpublished Hg isotope data from the Heather, Pentland, and Kimmeridge shales in the CNS graben, including gas condensate liquids from the CNS, North West Shelf of Australia (NWS), Philippines, and three oil samples from the Eastern Gulf of Mexico (EGOM) in the USA. Mercury isotope data for subsurface formations from the CNS are summarized in table S9, for hydrocarbons in table S10, and source rocks and hydrocarbons from Bohai Bay and Sichuan Basin in table S11, respectively. Mercury isotope data for Hg-enriched sediments are summarized in tables S12–S15 and include the following: OAE-2 sediments from the type locality in Rehkogelgraben (table S12), Cambrian black shales from Maoshi, Zhijin, and Paiting (table S13), PTB sediments (table S14), and LPE sediments (table S15), respectively.

2.3. Laboratory analyses

All of the Hg isotope data in tables S9 and S11 were measured at ALS Scandinavia AB, (Lulea, Sweden), a commercial laboratory that provides Hg isotope analyses. Details concerning sample preparation, instrumentation and analysis are provided in a separate section on mercury isotopes in the Data and Supporting Information section. Hg isotopes for the three EGOM oil samples in table S10 were analyzed at the University of Michigan Hg isotope laboratory.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Mass dependent fractionation of Hg isotopes

3.1.1. Cinnabar deposits

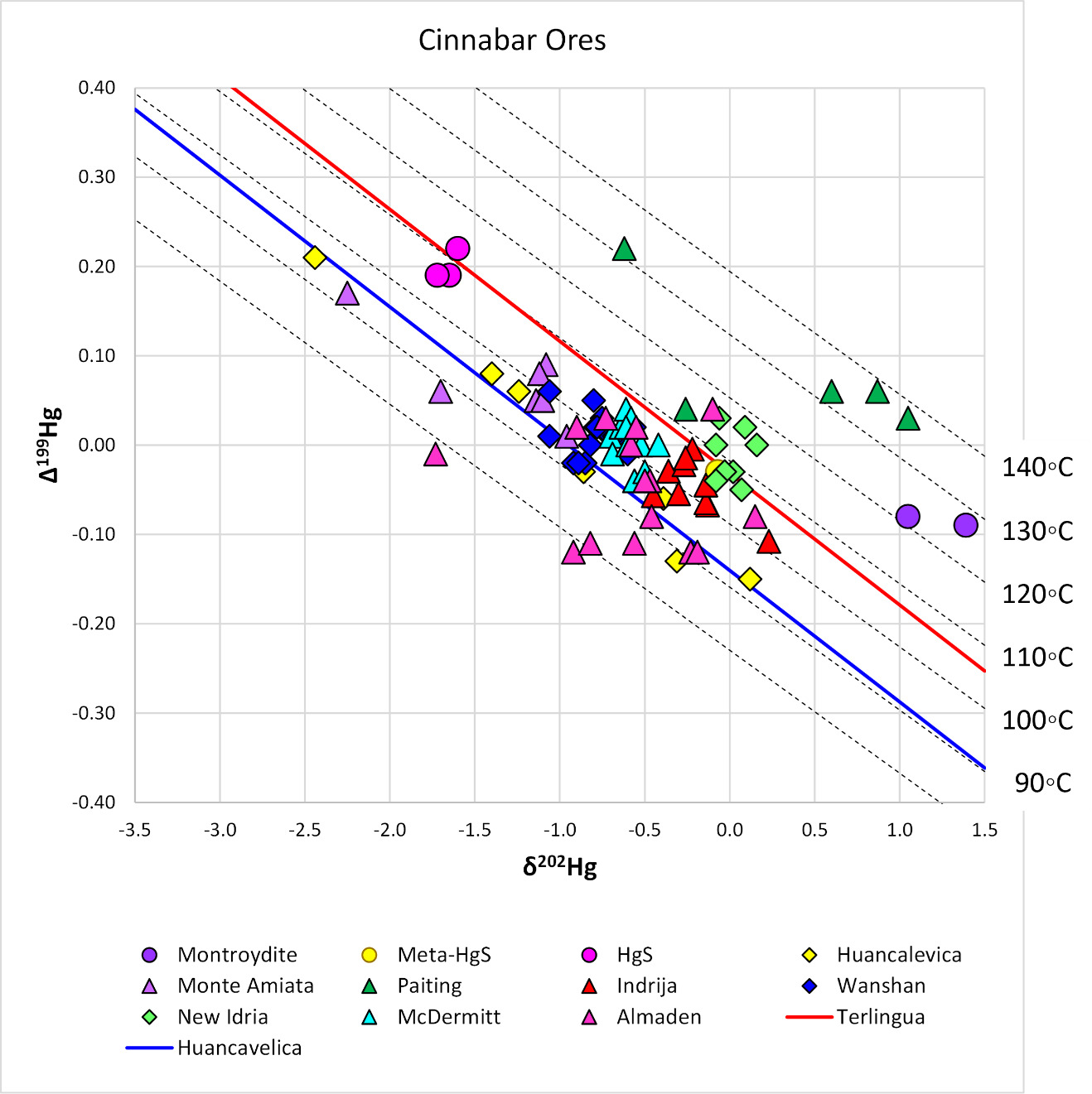

Mercury isotope data from Terlingua ore minerals, OAE-2 sediments, Huancavelica (Peru), McDermitt (Nevada, USA), Indrija (Slovenia), Almaden (Spain), Wanshan and Paiting (SW China), and Monte Amiata (Tuscany, Italy) are shown in figure 1. Mercury-bearing ore minerals from the Terlingua and Huancavelica deposits display large ranges in MDF (δ202Hg = −3 to 0‰), and an equally large range in MIF, with Δ199Hg ranging from −0.1 to almost 0.4‰. Of all the deposits in table 1, cinnabar ores from Paiting are the most enriched in 202Hg. With this exception, cinnabar from all of the other major Hg deposits in table 1, regardless of host rock age, have a very tight distribution for both MDF and MIF Hg isotope fractionation, ranging from δ202Hg = ~0 to −1‰, and Δ199Hg = 0 ± 0.1‰. Values of δ202Hg for cinnabar from New Idria in the California Coast Range are consistent with the same linear isotope trends as observed for Terlingua, and the Hg isotopic composition for a suite of OAE-2 rocks from the chrono-stratigraphically equivalent type section in Rehkogelgraben, Austria (Bryndzia, 2023; Yao et al., 2022). There are no published Hg isotopic data for associated sediments from the Texas, Peruvian or Tuscany deposits.

The range of Δ199Hg observed in the cinnabar ore for Hg deposits in table 1 closely matches that of an upper mantle source, represented by continental flood basalts (CFB; Yin et al., 2022). It should be noted that cinnabar ores in all of these Hg deposits are enriched in 202Hg relative to the average mantle Hg isotopic composition. One sample of Almaden cinnabar ore actually plots on the mantle isotopic composition.

The study by Palero-Fernández et al. (2015) addressed the question of timing for Hg ore formation in the Almaden district using Pb-Pb isotope age-dating techniques. Many of the samples analyzed by Palero-Fernández et al. (2015) were also analyzed for their Hg isotopic compositions by Gray et al. (2013). The Pb-Pb ages and Hg isotopic data for Almaden cinnabar data are summarized in table S7 and figure S1. Despite being hosted in the lower Silurian–early Devonian age Criadero Quartzite, only two of eleven cinnabar samples have corresponding host rock ages. Most of the Almaden cinnabar ores have Pb-Pb ages that are either Permian–Triassic or Jurassic–early Cretaceous in age. One sample has an unusually young Oligocene Pb-Pb age. Based on their disparate Pb isotope age data Palero-Fernández et al. (2015) went to great lengths to explain the source of Pb and the very broad range of ages for this giant Hg deposit. However, there is almost no discussion concerning the source(s) of Hg in the Almaden cinnabar ores.

3.1.2. Source rocks

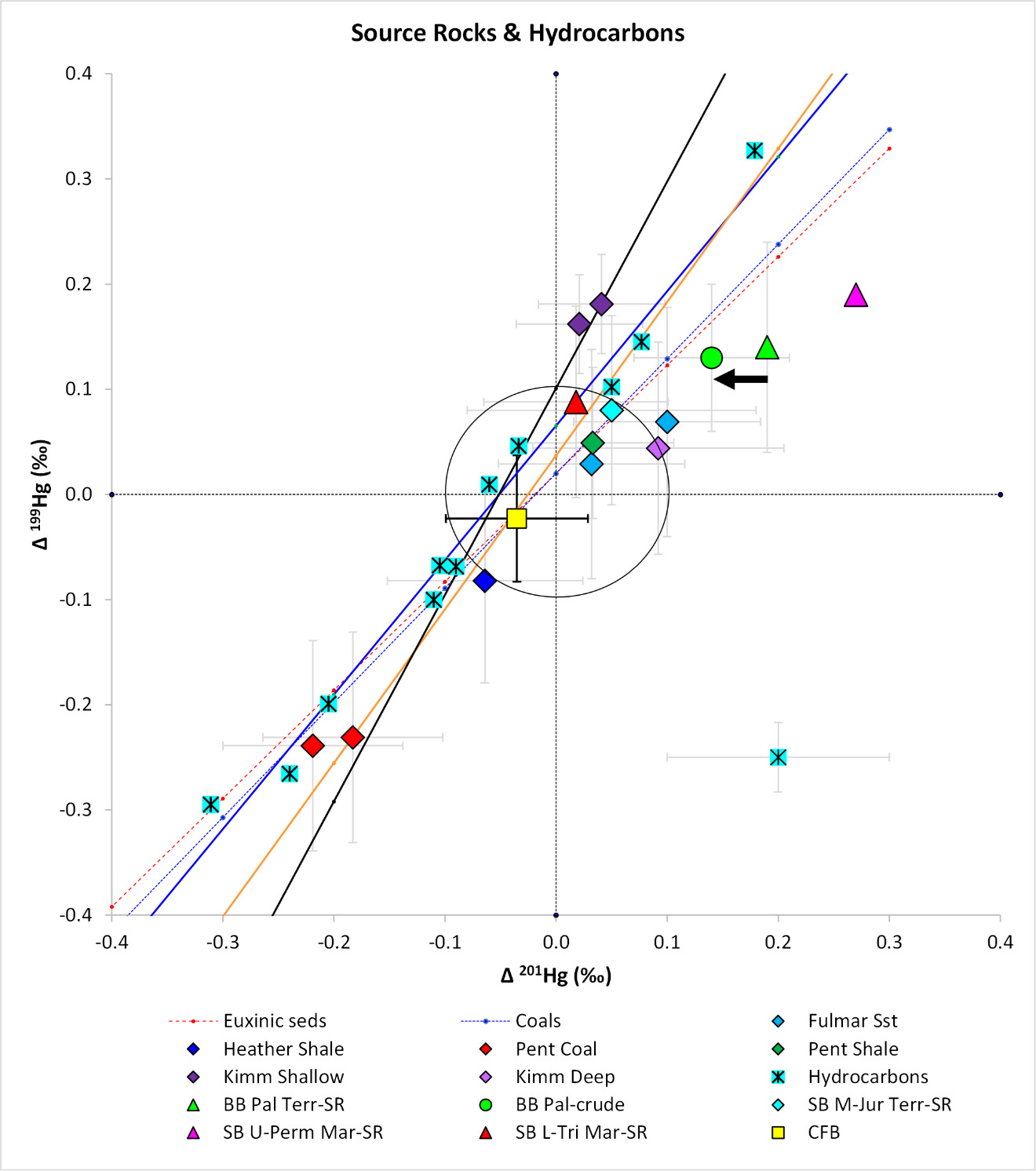

Figure 2 shows a δ202Hg versus Δ199Hg plot of Hg isotope data for a suite of source rocks and hydrocarbons from China, the CNS, NWS, EGOM, and the Philippines. Mercury data for source rocks and hydrocarbons are summarized in table S9, table S10, and table S11, respectively. The Hg concentrations reported in table S11 are for source rocks from China studied by Zhou et al. (2023), and are averages of samples for which Hg isotopes were measured. The range of Hg concentrations in the Bohai Bay terrestrial source rocks are generally low, averaging ~27 ± 15 ppb (n=38; ± 1σ) in Paleogene terrestrial source rocks. Upper Permian marine source rocks contain a very low concentration of Hg, averaging ~5 ± 4 ppb (n=4; ± 1σ), while Lower Triassic marine source rocks contained the highest Hg concentration, averaging ~60 ± 75 ppb (n=4; ±1σ).

Concentrations of Hg for CNS source rocks are quite variable, and range from ~18 ppb in Pentland shale, and ~46 ppb in the deep Kimmeridge and Heather shales, respectively (table S8). On average, these values are similar to the concentration range observed in source rocks from the Sichuan Basin and Bohai Bay by Zhou et al. (2023). By contrast, both the shallow Kimmeridge shale and Pentland coal are much more enriched in Hg, with the Pentland coal samples containing concentrations of 281 and 374 ppb Hg, while the shallow Kimmeridge shale samples contain 242 and 235 ppb Hg, respectively (table S8). The Hg enriched CNS source rocks have Hg concentrations consistent with those reported by Grasby et al. (2019; their fig. 2), for key extinction boundaries and oceanic anoxic events through geologic time.

The black rectangle in figure 2 outlines the area of clastic source rocks (this study; excluding Pentland coals) that include Paleogene-age terrestrial source rocks from Bohai Bay (BB, China), and both marine and terrestrial source rocks ranging in age from early to late Jurassic (CNS) to middle Jurassic in the Sichuan Basin (SB, China). The dashed black line is a best fit to the CNS source rock data and is highlighted here because it shows that all of the potential source rocks in this part of the CNS likely contain an upper mantle Hg component, as indicated by the fact that the average CFB composition plots almost exactly on the CNS source rock trend.

3.1.3. Hydrocarbons

Mercury concentrations for liquid hydrocarbons are summarized in table S10 and includes samples from CNS, NWS, EGOM, and the Philippines. Samples from the EGOM are oils, while the remainder are gas condensate liquids. Concentrations of Hg are quite variable, and reflect similar ranges to that observed in source rocks, ranging from ~6 ppb to 307 ppb in samples from the CNS, to almost 880 ppb in a sample from the Philippines. Two of the condensate samples from the CNS are also enriched in Hg, with Hg concentrations of 137 and 307 ppb, respectively. It is reasonable, therefore, to infer that some of the hydrocarbons in the CNS likely derived their Hg from proximal Hg-enriched source rocks. Oils from the EGOM show a similar range of Hg enrichment also likely reflecting different Hg concentrations in their source rocks. The Hg enrichments observed in some of these hydrocarbon liquids are similar to ranges reported by Bryndzia et al. (2023) for Hg solubility in hydrocarbons.

Mass dependent fractionation of Hg isotopes in hydrocarbon liquids shown in figure 2 are somewhat unusual, with a subset of hydrocarbon samples displaying significant depletions in MDF, with δ202Hg ranging from −2.5‰ to −5‰, and Δ199Hg ranging from −0.1 to 0.3‰ . Another subset of hydrocarbon samples mirrors an opposite trend, with significant enrichment in 202Hg, with δ202Hg = −2.5‰ to 0.5‰, plotting almost exactly on the MDF trend observed in Terlingua Hg ore minerals and OAE-2 sediments. The remaining three hydrocarbon samples show almost no MDF (δ202Hg = −1.5 to −2‰), with Δ199Hg = −0.3 to 0.1‰. Two of the EGOM oil samples plot on the Terlingua MDF-MIF and OAE-2 sediments trend.

3.2. Mass independent fractionation of Hg isotopes

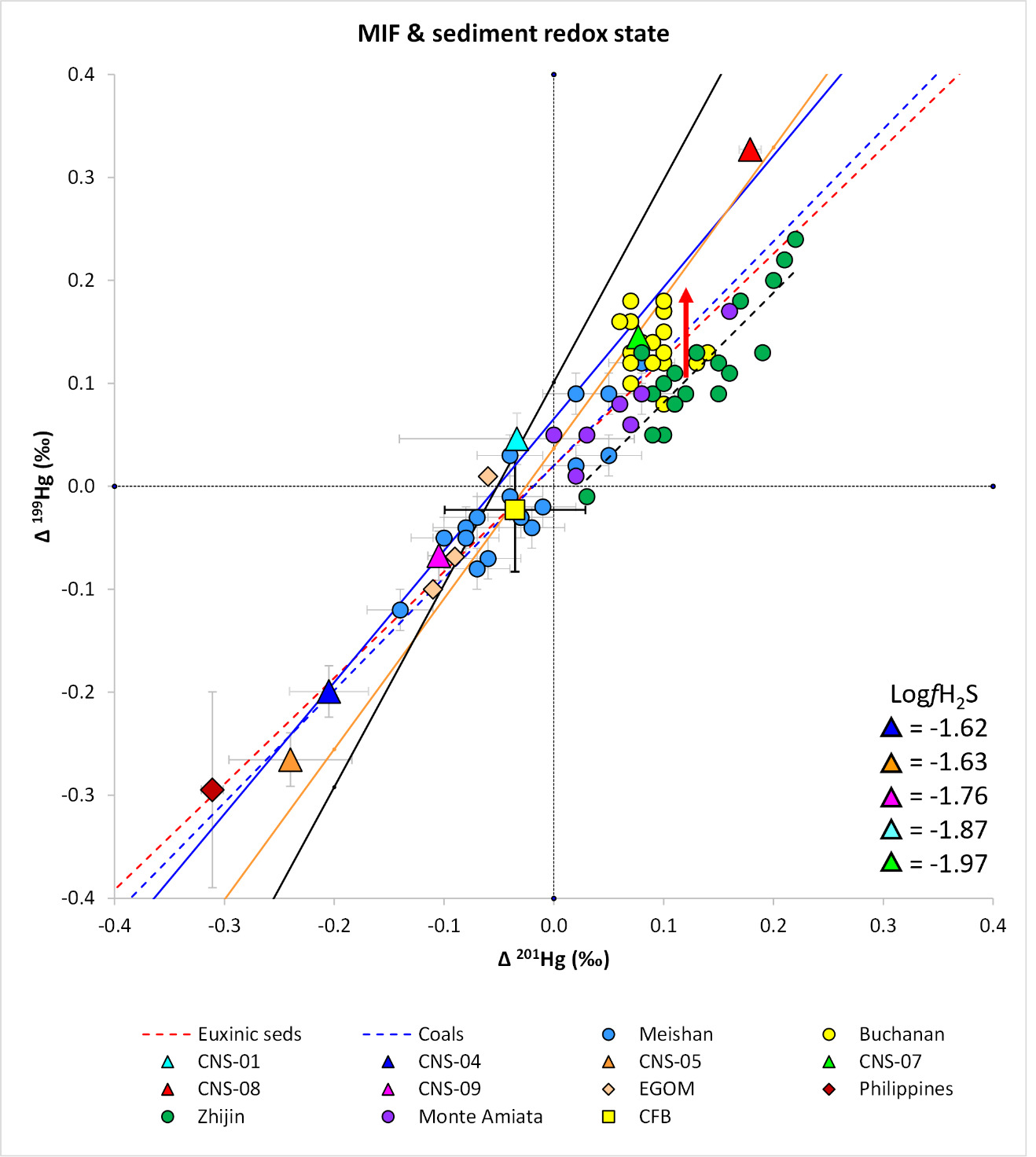

Figure 3 shows the MIF of Hg isotopes for Hg deposits in table 1. Approximately 80% of the data (67 of 86 samples) plot within ± 0.1‰ of the origin, with many samples statistically indistinguishable from the MIF ranges of the upper mantle CFB Hg isotopic composition. Clear outliers on this plot are Hg ore minerals from Terlingua, and a few samples each from Almaden, Huancavelica, and Monte Amiata. Both cinnabar and hydrocarbons display strong positive and negative MIF. It is challenging to explain the distribution of the cinnabar data on this plot in terms of the broad groupings proposed by Moynier et al. (2021) and Yin et al. (2022), that distinguish domains for marine (positive MIF) and terrestrial reservoirs (negative MIF) for the source of Hg in various natural environments. On the Yin et al. (2022) MIF plot, almost all of the cinnabar ore minerals shown in the black circle in figure 3 would be considered to have a mantle source.

Figure 4 includes all of the source rocks and hydrocarbons discussed in figures 2 and 3, in addition to the bulk of the cinnabar data from figure 3 (black circle). Cinnabar ores from Terlingua and Huancavelica, and hydrocarbons, all show strong linear trends on the MIF Hg isotope plot. Both Terlingua and Huancavelica Hg ore minerals and associated hydrocarbons display positive Δ199Hg fractionation relative to the bulk of the cinnabar ore data (black circle), and the isotopic trends for coals and euxinic sediments. Linear regressions defining trends for these three groups are shown in table 2. The solid black arrow in figure 4 indicates the MIF of Δ201Hg isotopes due to hydrocarbon generation from the Bohai Bay Paleogene terrestrial source rock from Zhou et al. (2023). The magnitude of this MIF is ~0.5‰. Hydrocarbon generation occurs with negligible MIF of Δ199Hg, and only minor depletion of Δ201Hg. This also appears to be true for most of the source rocks in figure 4. Despite the apparently large analytical uncertainties associated with these data, hydrocarbons in general always appear to be depleted in Δ201Hg relative to the general distribution of source rocks in figure 4. The only exceptions appear to be Upper Jurassic-age Kimmeridge shale and Lower Triassic marine source rock from the Sichuan Basin. It is also curious to note that the Bohai Bay Paleogene terrestrial source rock has pronounced positive Hg isotope MIF, and according to the designation of Moynier et al. (2021) and Yin et al. (2022), plots in the marine reservoir of Hg together with other marine source rocks. There are no published δ199Hg or δ201Hg data available for OAE-2 sediments from which to estimate and plot their Δ199Hg or Δ201Hg isotopic composition on figure 4. However, it is likely that they would closely track the linear trend observed for the Hg ore minerals in the Terlingua cinnabar ore deposits shown in figure 4. According to the classification of Yin et al. (2022), the Terlingua cinnabar deposits would be consistent with having a marine source for most of the Hg in their ore minerals (strong positive MIF). Similar inferences could be made for the Hg in the cinnabar ore minerals from the Huancavelica deposits in Peru, which also have samples with strong negative MIF, indicative of a terrestrial source of Hg (fig. 3).

4. DISCUSSION

4.1. Source rocks in the CNS graben

Source rocks from the CNS graben are the principal focus of this section since they provide the most representative example for the initial source of mantle-derived mercury being sequestered in organic-rich source rock sediments, and shows the impact of early diagenesis and subsequent thermal maturation of the organic matter on the isotopic composition of Hg isotopes in associated hydrocarbons.

There are potentially five source rocks in the CNS graben, including four shales and the Pentland coal. The Pentland coal and the Upper Jurassic-age Kimmeridge shale represent different environments of deposition (fig. 4), with the Pentland coal end-member forming in a near surface estuarine environment i.e., marine-terrestrial, while the shallow Kimmeridge shale end-member is clearly marine. Both the Pentland coal and Kimmeridge shale are enriched in Hg, with the shallow Kimmeridge samples containing 235 and 242 ppb Hg, respectively. The largest reservoir for Hg in the subsurface CNS formations is the Pentland coal, with Hg concentrations of 281 and 374 ppb, respectively (table S9). It is possible, therefore, that any of the CNS hydrocarbon samples in figure 2 could represent mixtures of hydrocarbons generated from either or both of these two Hg-enriched sediments (fig. 2). In TOC rich intervals, the environment of deposition is expected to be reducing and anoxic, or even euxinic, and favorable for sequestering Hg (Them et al., 2019).

This work shows that certain organic-rich source rocks are enriched in Hg, well above normal crustal abundances. However, many organic-rich source rocks contain much less Hg than the average crustal abundance of ~62.4 ppb Hg (Grasby et al., 2019). An excellent case in point are the shallow and deep Kimmeridge shales facies of the CNS graben (table S9). The shallow Kimmeridge black shale contains ~240 ppb Hg, while the deeper shale contains only ~46 ppb Hg. Black shales and marls in OAE-2 sediments from the lower Eagle Ford formation in SW Texas are similarly enriched, with Hg concentrations ranging from ~200–250 ppb in low-maturity organic-rich source rocks, and up to ~750 ppb from the producing sour black oil zone in the lower Eagle Ford formation, representing an enrichment of Hg in hydrocarbons by a factor of 3 (Bryndzia, 2023; Scaife et al., 2017).

4.2. Hydrocarbons

Within analytical uncertainty, two of the CNS hydrocarbon samples in figure 2 plot close to the Pentland coal, while four of the CNS hydrocarbon samples appear to plot linearly displaced towards more depleted δ202Hg isotopic compositions relative to their shale source rocks. The most striking aspect of the data in figure 2 is the very large MDF and MIF fractionation observed in the liquid hydrocarbons. The range of δ202Hg in shales and coals ranges from ~ −1‰- −3‰, but in the liquid hydrocarbons it is almost three times larger, ranging from ~-5‰ to 0.5‰. Values of Δ199Hg in source rocks ranges from ~ −0.25‰ to 0.2‰, while for liquid hydrocarbons the range is even larger, with Δ199Hg = −0.1‰ to 0.3‰.

Figure 2 shows the results of liquid hydrocarbons generated under laboratory conditions from Paleogene terrestrial source rocks (Bohai Bay; Zhou et al., 2023). The Bohai Bay oil-gas data are from production samples from Tang et al. (2019), and are almost indistinguishable from the laboratory generated oils from the same source rocks (table S11). The short solid black arrow in figure 2 shows that there is very little Δ199Hg MIF associated with the generation of hydrocarbons (liquids and gas), with a minor increase in the MDF, resulting in relative enrichment of 202Hg in the generated hydrocarbons.

A similar inference may be made for the three oil samples from the EGOM, which show a similar enrichment in 202Hg in hydrocarbon liquids generated from a source rock that is presumably proximal in origin to the dashed black source rock line in figure 2. The source rock for the EGOM oil samples is the upper Jurassic Haynesville Formation (Godo, 2017), an organic-rich black shale, age-equivalent to the Upper Kimmeridge source rock shale in the CNS. The data in figure 2 suggest that generation of liquid hydrocarbons from a source rock involves significant MDF, with both enrichment and depletion of 202Hg, but with little MIF of Δ199Hg, as also observed by Chen et al. (2022) and Liu et al. (2022).

Experimental work by Indraswari et al. (2024) also generated hydrocarbon liquid from laboratory thermal maturation experiments on marine type II organic matter in Toarcian-age cores from the Lower Saxony Basin in Germany (Posidonienschiefer – Early Jurassic). A comparison of Hg data from three cores of increasing relative thermal maturity showed that Hg content in the mature/overmature sediments increased by over a factor of 2 compared to Hg in the immature cores. Hg enrichments in the highest maturity samples were found to be similar to the peak Hg anomaly in Siberian Traps (396 ppb; Wang et al., 2018), and Deccan Traps (415 ppb; Sial et al., 2013). However, the mechanism of enrichment was not determined. They speculated that it was due to volatilization of Hg during heating. No Hg isotope data were included in the results of their study. One obvious explanation for the observed enrichment in Hg with thermal maturation is that Hg0(org) was preferentially partitioned into a residual (liquid and/or bitumen) hydrocarbon phase.

Relative to the general Hg isotopic composition of hydrocarbon source rocks in figure 2 (black rectangle), two contrasting MDF Hg isotope trends are apparent in the hydrocarbon data. One trend clearly aligns with that observed in OAE-2 sediments and cinnabar ore minerals from Terlingua and Huancavelica (red and blue solid lines, respectively), and shows pronounced enrichment of 202Hg. The other trend, typical of gas condensate liquids in the HP/HT CNS samples shows the opposite trend, with large depletions in 202Hg, with δ202Hg reaching ~−5‰.

One potential explanation for the observed depletion in 202Hg in the gas condensate liquids could be attributed to volatilization of 198Hg0(g) during thermal maturation of original kerogen in the shale source rock, as postulated by Indraswari et al. (2024). These samples are at present day reservoir temperatures ranging from ~171 to 182 ºC. Gas condensates occur as a single phase, heavy molecular weight gas in subsurface reservoirs and it is reasonable to suggest that Hg0(g), with its high vapor pressure, would preferentially fractionate the lighter mass 198Hg isotope into a coexisting gas phase, as observed in the CNS gas condensate samples shown in figure 2, and confirmed experimentally by Estrade et al. (2009).

The solid-colored arrows in figure 2 show the expected volatilization trend of Hg0(g) generated from CNS source rocks (colored diamonds) located within the black rectangle, and could explain the observed depletion in 202Hg relative to its source rock composition. MDF due to volatilization of 198Hg0(g) is significant, and apparently occurs without any MIF of Δ199Hg. The similarity in range of Δ199Hg for both source rocks and hydrocarbons in figure 2 suggests that the Δ199Hg isotopic composition of hydrocarbons is controlled by the Δ199Hg isotopic composition of source rocks from which they were generated.

4.3. The role of hydrocarbons in cinnabar ore formation

A feature common to most cinnabar deposits is the ubiquitous presence of liquid hydrocarbons and bitumen, often giving rise to the term “hydrothermal petroleum” to describe the ubiquitous presence and role of hydrocarbons in the formation of most cinnabar deposits e.g., Yates et al. (1951), Yates and Thompson (1959), Bailey and Everhart (1964), Klemm and Neumann (1984), Krupp (1988), Noble and Vidal (1990), Saupe (1990), Peabody and Einaudi (1992), Spangenberg et al. (1999), Lavrič and Spangenberg (2003), Stetson et al. (2009), Wiederhold et al. (2013), Palero-Fernández et al. (2015), Schito et al. (2022), and Bryndzia (2023).

All of the giant cinnabar deposits shown in table 1 are associated with some form of hydrocarbon, either as liquid oil and/or bituminous residue after thermal degradation of original organic matter. In the case of the Terlingua deposits in SW Texas, Bryndzia (2023) showed that the Hg was likely remobilized both as Hg0(org) and Hg0(aq). Some of the purest and highest-grade cinnabar ores were formed as replacement deposits of fine grained smectitic clay minerals (Yates & Thompson, 1959), suggesting that Hg2+ was associated with smectitic clays formed as a result of hydrous alteration of siliceous volcanic debris, notably ash, glass and tuffaceous material. In the Terlingua deposits, thermal heating by intrusion of tabular igneous bodies generated liquid hydrocarbons that migrated into structurally favorable ore forming sites. Further analysis showed that both the age and cinnabar mineralization common in the California Coast Range deposits (New Idria and New Almaden), and Huancavelica (Peru) all likely formed in the same way, with Hg derived from Cenomanian-age organic-rich black shales, marls and interbedded tuffs i.e., OAE-2 sediments. All of these cinnabar deposits formed from sediments with similar isotopic compositions to those captured for the cinnabar deposits shown in figures 1, 2 and 3.

In addition to the ubiquitous presence and role that liquid hydrocarbons play in the formation of giant cinnabar deposits, the other critical component is H2S. The primary control on cinnabar deposition is the ambient redox state. Significant concentrations of Hg0(org) dissolved in liquid hydrocarbons are only possible in the presence of a relatively high fugacity of H2S i.e., fH2S. It is the oxidation of H2S and Hg0 that results in the deposition of cinnabar ores, generally brought about by mixing of migrating liquid hydrocarbons and associated formation brines, at shallow crustal levels with oxygenated meteoric waters (Bryndzia, 2023; Bryndzia et al., 2023; Krupp, 1988; Peabody & Einaudi, 1992).

4.4. Relationship between Hg isotopes in cinnabar ores and sediments/sedimentary rocks

4.4.1. Monte Amiata

Figure 5 shows the Hg isotopic composition of cinnabar from Terlingua and the Monte Amiata district in Tuscany (Italy), the third largest deposit of Hg in table 1. For such an historically significant Hg mining district surprisingly little is known about the source of Hg in the Monte Amiata deposits (D’Orazio et al., 2021; Klemm & Neumann, 1984; Rimondi et al., 2015; Schito et al., 2022). Descriptions of ore textures and mineralization by Klemm and Neumann (1984) are remarkably similar to those described for the Terlingua deposits by Yates and Thompson (1959), which Bryndzia (2023) showed were related to the organic-rich marls, claystones, black shales and altered tuffs forming part of the Cenomanian–Turonian OAE-2 sediments in the Terlingua mining district. Figure 5A shows that cinnabar ores from the Monte Amiata deposits plot between the Huancavelica and Terlingua ore trends. The Monte Amiata cinnabar ores are the only ones to confirm a strong genetic relationship to euxinic sediments, with a uniform slope of ~1 on the MIF plot in figure 5B.

Due to the emplacement of the Monte Amiata volcano and related intrusive igneous rocks at ~0.3 Ma, much of the critical sedimentary stratigraphy in the Monte Amiata district is missing. OAE-2 sediments of Cenomanian–Turonian age are known to outcrop in the “Scaglia Toscana” formation in the Northern Apennines of northern Tuscany (D’Orazio et al., 2021). The rocks of this formation consist of shale, marl, marly limestone, calcilutite, calcarenite, radiolarite and calcareous-siliceous breccia. The black shales are also enriched in carbonaceous matter, containing 2–12 wt.% total organic carbon (TOC). Based on the hyper-enrichment in the elements Cd, Ag, Zn, Sb, Cu, Mo, V, Pb, and Tl in these sediments, D’Orazio et al. (2021) concluded that the black shales were deposited in a strongly anoxic and euxinic depositional environment, consistent with their MIF Hg isotopic composition in figure 5B. No Hg concentrations were reported for any of these sediments, which is surprising in view of the fact that they were so enriched in Zn (18,169, 12,581 ppm) and Cd (171, 94 ppm), and all are Group 12 elements.

4.4.2. Wanshan and Paiting

Figure 6 shows Hg isotopic data for the Cambrian-age Wanshan and Paiting cinnabar ores in SW China, including organic-rich, euxinic black shales from Maoshi and Zhijin (Yin et al., 2017; table S13), and black shales and tuffs from the Paiting Hg deposit (Ni et al., 2022; table S13). In figure 6A, many of the sediments plot in the source rock rectangle, while a significant number of samples also plot on the hydrocarbon-HgS mineralization trends for Terlingua and Huancavelica (red and blue lines, respectively). Cambrian black shales from both Maoshi and Zhijin are excellent source rocks, with very high levels of organic carbon and sulfur, and would have readily generated liquid hydrocarbons and H2S from which the cinnabar ores would have been deposited. In figure 6A, Zhijin sediments in particular show significant enrichment in 202Hg, approaching that observed in Wanshan cinnabar ore, while the Maoshi sediments show enriched δ202Hg isotopic composition, with almost no variation in Δ199Hg, consistent with loss of 198Hg0(g). Tuffs and black shale from the Paiting Hg deposit plot between the Terlingua and Huancavelica cinnabar ore trends, with most of the tuffs plotting in a tight cluster with the Wanshan cinnabar ores.

In figure 6B the Zhijin sediments all lie in the domain of positive Hg isotope MIF where the dominant source of Hg is likely marine. Most of the Hg in the Wanshan cinnabar ores has a near zero MIF of Hg isotopes, consistent with an upper mantle isotopic signature. It does not appear that Hg in Wanshan and Paiting cinnabar ores was derived from either Maoshi or Zhijin black shales since there is almost no overlap in the Hg isotopes between these Cambrian-age sediments and cinnabar ores in figure 6B. The Hg isotopic signature of Wanshan cinnabar ores is very similar to those in basement tuffs and black shales from the Paiting deposit, suggesting that these were the most likely progenitor sediments for the Wanshan and Paiting cinnabar ores. The slope of Δ199Hg/Δ201Hg for cinnabar from the Paiting Hg deposit ranges from 1.5 to 2, similar to cinnabar from Terlingua and Huancavelica. Ni et al. (2022) concluded that the Hg in the Paiting Hg deposit was mostly derived from Cambrian black shales. However, the Hg isotopic data in figure 6 strongly suggests that most of the Hg in Wanshan and Paiting cinnabar ores was derived from basement tuffs and related Cambrian black shales, and not the Maoshi or metalliferous Zhijin black shales.

4.4.3. Almaden, Indrija, and PTB sediments

The results of a similar exercise for cinnabar ores and Hg-enriched Permian–Triassic boundary (PTB) sediments are shown in figure 7 for the cinnabar ores from Almaden and Indrija. The PTB sediments include those identified as belonging to “trend II” by Sial et al. (2020; table S14), and include PTB samples from Indrijca (Slovenia), Rizvanusa (Croatia), Seres-101 (Southern Alps), and Hovea-3 (1980-94; SW Australia). Also plotted are Hg-enriched PTB sediments from Buchanan Lake (Canadian Arctic) from Grasby et al. (2017). In figure 7A, most of the PTB sediments plot within the source rock rectangle, including a few samples from Meishan. Most of the Meishan samples are enriched in 202Hg and plot between the source rock rectangle and cinnabar ores of the same age. Several of the Meishan samples plot on the cinnabar ore trend relative to PTB samples. Note that all of the Buchanan Lake samples are enriched in 202Hg relative to source rocks and other PTB sediments, including Meishan. By contrast, on the MIF Hg isotope plot in figure 7B, excellent agreement is observed between the PTB sediments from both sources, with almost complete overlap in the Hg isotopic compositions of cinnabar ores from both Almaden and Indrija. The latter observation strongly suggests that the dominant source of Hg in both the Almaden and Indrija cinnabar deposits is related to the PTB Hg-enriched sediments produced by the Siberian Traps LIP (STLIP).

According to Saupe (1990), the most probable source of mercury in the Almaden district is Ordovician black shale. However, there are also contemporaneous late Silurian–early Devonian black shales that form both hanging wall and footwall, respectively, to the Criadero Quartzite. Another Middle Black Shale unit occurs within the Criadero Quartzite, and all three shales are proximal to, or in direct contact with, the most Hg-rich syngenetic ore seams in Almaden (Palero-Fernández et al., 2015; their figure 7). There are no Hg isotope data available for any of these organic-rich black shales with which to correlate a potential LIP event or major source rock interval.

4.5. δ202Hg isotope thermometry

Estrade et al. (2009) analyzed the Hg isotopic composition of Hg0(g) during Hg0(liq) evaporation experiments, both under equilibrium and dynamic mode fractionation conditions. For dynamic mode evaporation, they observed that the Hg isotopic composition of the condensed vapor phase was a strong function of temperature (Estrade et al., 2009; their fig. 3). The relationship they obtained is given by equation (1):

δ202Hg = 9.44 − 1.40∗106/T2 (K)

If Hg in the residual Hg pool preserves its isotopic composition when in equilibrium with cinnabar, using equation (1), it is possible to solve for the temperature at which cinnabar was in equilibrium with 198Hg0(g). The results of this exercise for hydrocarbons are shown in table 3, and for cinnabar ores in table S16, respectively.

The inferred temperatures for the evaporation of Hg0 observed in 202Hg depleted gas condensate samples from the CNS are consistent with the experimental results of Estrade et al. (2009), and is taken as evidence in support of 198Hg0(g) evaporation in organic-rich source rocks. If correct, the data in table 3 show that the evaporation of 198Hg0(g) in source rocks generating δ202Hg depleted hydrocarbon isotopic compositions is a relatively low temperature process. The evaporation of 198Hg0(g) likely began early in the burial history of the source rock, coincident with the onset of the oil generation window at temperatures of ~65–80 °C (Horsfield & Rullkotter, 1994; Tissot & Welte, 1984). By contrast, the δ202Hg isotopic composition of black oil samples in table 3 indicate much higher temperatures, similar to those inferred for cinnabar formation in table S16.

Assuming equilibrium of 198Hg0(g) evaporation temperatures with Hg0(liq) in the cinnabar forming reaction (eq 2; Bryndzia et al., 2023; Krupp, 1988) a model based on

Hg0(liq) + 0.5O2 + H2S ⇌ HgS + H2O

multiple linear regression of Δ199Hg, δ202Hg and temperature (eq 1), resulted in the model isotherms shown in figure 8. The upper limit of measured evaporation temperatures in Estrade et al. (2009) was 100 °C, so some extrapolation of the model to higher temperatures is required to accommodate all of the data. The model shows that the majority of cinnabar ores formed over a temperature range of ~80–140 °C, with samples from Almaden forming at the lowest temperature, and samples from Paiting indicating the highest formation temperatures of any major cinnabar deposit (fig. 8 and table S16).

A paucity of documented formation temperatures for cinnabar deposits in general makes any comparison with the data in figure 8 challenging. In some deposits the true cinnabar formation temperatures are much higher than shown in figure 8, as for example at Paiting, where Ni et al. (2022) report ore forming temperatures of 200–290 °C; and at Indrija, where Palinkaš et al. (2004) report cinnabar formation temperatures of 160–218 °C. For Monte Amiata, Rimondi et al. (2015) report fluid inclusion homogenization temperatures in calcite ranging from 80–130 °C and 70–120 °C respectively, from two different deposits, in good agreement with inferred formation temperatures shown in figure 8. The solid red and blue lines in figure 8 are the “best fit” linear trends observed for cinnabar ores from the Terlingua and Huancalevica deposits shown in figures 1 and 2, respectively. Both trends are almost exact overlays of the model isotherms. The obvious conclusion to be drawn from figure 8 is that MDF of Hg isotopes in cinnabar formation is a kinetic process i.e., mostly a function of temperature, and contrary to recent conclusions presented by Yang et al. (2025), is unlikely to be a reliable indicator of Hg provenance.

The cinnabar-derived temperatures in figure 8 are remarkably similar to the temperatures obtained from two black oil samples in table 3, and suggests that the cinnabar temperatures reflect both hydrocarbon generation and cinnabar formation related processes. This could explain the close similarity in the δ202Hg isotopic composition between hydrocarbon liquids and cinnabar in figures 1 and 2. The onset of oil generation in a source rock is mostly a function of organic matter type, burial history, and kinetics of organic matter conversion (Horsfield & Rullkotter, 1994; Tissot & Welte, 1984). More importantly though, loss of a significant mass of 198Hg0(g) to an extant gas phase would enrich any condensed liquid and residual organic matter in 202Hg. This is a critical observation as it explains both the large depletions observed in the δ202Hg isotopic compositions of gas condensates in the CNS data, as well as the enriched δ202Hg isotopic composition observed in liquid hydrocarbons, cinnabar ores and OAE-2 sediments in figures 1 and 2. This is the fundamental characteristic of Hg isotopes common to all of the giant cinnabar deposits in table 1.

4.6. Δ199Hg/Δ201Hg ratios in hydrocarbons and cinnabar

Previous experimental and theoretical work has shown that slopes on Δ199Hg−Δ201Hg MIF plots may provide insights into the mechanism of MIF fractionations observed in nature (Estrade et al., 2009; Ghosh et al., 2013; Schauble, 2007; Wiederhold et al., 2010). Linear regression of MIF slopes i.e., Δ199Hg/Δ201Hg in figure 9 for Hg in Terlingua and Huancalevica cinnabar ores, and hydrocarbons were calculated using the errors-in-variables model (option 1) in the online version of IsoplotR software (https://isoplotr.geo.utexas.edu). Estimated 2σ in Δ199Hg is ± 0.08 and ± 0.055 for cinnabar from Terlingua and Huancalevica, and ± 0.033 for hydrocarbons, respectively, while estimated uncertainties in Δ201Hg are ± 0.09 and ± 0.05 for cinnabar from Terlingua and Huancalevica, and ± 0.078 for hydrocarbons, respectively.

The hydrocarbon Δ199Hg/Δ201Hg slope in figure 9 is 1.30 ± 0.69 (2σ). This is almost identical to that reported for photoreduction of CH3Hg+ to Hg0 of 1.36 ± 0.03, attributed by Bergquist and Blum (2007) to the magnetic isotope effect (MIE) for MIF of Hg isotopes. It is possible that this is an inherited isotopic signature of photoreduction in the atmosphere or a shallow water setting i.e., photic zone, in the presence of dissolved organic matter, as proposed for Hg in sediments from Buchanan Lake by Grasby et al. (2017).

In the domain of negative MIF, the hydrocarbons plot almost exactly on the trends associated with euxinic sediments and coals. The slopes of the MIF isotopic fractionation for euxinic sediments and coals are 1.09 and 1.03, respectively (Zheng et al., 2018). Photoreduction in this environment most likely represents the reduction of Hg2+(aq) in the presence of organic matter, in a very reducing environment in which H2S is also likely to be present i.e., photic zone euxinia (PZE). By contrast, in the domain of positive MIF (marine reservoir of Hg), hydrocarbons deviate significantly from the coal and euxinic MIF trends with Δ199Hg/Δ201Hg ratios >1.0.

The MIF slopes observed in cinnabar from Terlingua and Huancavelica have Δ199Hg/ Δ201Hg slopes of ~1.49 ± 0.69 (2σ) and 2.05 ± 0.77 (2σ), respectively (table 2). Within analytical uncertainty these slopes are statistically the same as that reported by Wiederhold et al. (2010) for the equilibrium Hg isotope fractionation between dissolved Hg2+ and thiol-bound Hg, the dominant Hg-binding groups in natural organic matter, with a Δ199Hg/ Δ201Hg ratio of 1.54 ± 0.44 (2σ). Ghosh et al. (2013) confirmed these results, reporting a Δ199Hg/ Δ201Hg ratio of 1.59 ± 0.05 (2σ). Wiederhold et al. (2010) and Ghosh et al. (2013) both proposed that an MIF slope of Δ199Hg/ Δ201Hg of ~1.6 may be used to distinguish the nuclear volume effect (NVE) for MIF fractionation of Hg isotopes from the magnetic isotope effect (MIE) in natural samples and kinetic reactions.

4.7. Redox state and isotopic fractionation of Hg isotopes

The final stage in the development of a cinnabar deposit involves oxidation of Hg0(org, aq) and H2S to form cinnabar, as shown by equation (2). Oxidation of Hg0 to Hg2+ is what defines the cinnabar ore deposition trend in the MDF-MIF Hg isotope plots shown in figures 1, and 2. These observations are also consistent with theoretical predictions that both mass dependent and nuclear volume fractionation mechanisms will enrich the heavy isotopes in the oxidized Hg species as compared to the reduced counterpart. More generally, nuclear-volume isotope fractionation will concentrate larger (heavier) nuclei in species where the electron density at the nucleus is small - due to lack of s-electrons e.g., oxidized Hg2+−[Xe]4f145d106s0 versus reduced Hg0− [Xe]4f145d106s2 (Schauble, 2007).

The increase in slope of hydrocarbons from the euxinic sediment and coal trends as indicated by the sediments from Buchanan Lake in figure 9 strongly suggests that the cause of the MIF in Δ199Hg for Hg in both cinnabar and in hydrocarbons may be controlled by the sediments themselves. Zheng et al. (2018) proposed that the negative Hg MIF isotope signature observed in organic-rich sediments in the geologic record, reflect reducing conditions in which H2S is present in the absence of free oxygen i.e., PZE. He also suggested that in an oxic environment a positive MIF Hg isotope signature should be expected. Grasby et al. (2017; their fig. 3A) compared the Hg isotopic MIF in two different sets of PTB sediments, one from Buchanan Lake in the Canadian arctic, and the other from Meishan, in China. Both represent sediments from the PTB, but their environments of deposition were quite different, with Meishan representing a near-shore, shallow marine environment, while Buchanan Lake was representative of an open and deep marine environment. Comparison of Hg isotope systematics for these two different PTB sediments for MIF-MIF of Hg isotopes is shown in figure 9.

The essential differences in the Hg isotopes between the two PTB data sets is that Meishan sediments plot along the euxinic sediments and coal trend in figure 9, while the Buchanan Lake samples are all mostly enriched in Δ199Hg relative to the Meishan sediments and the euxinic sediments and coal trends. This suggest that Hg in the Buchanan Lake sediments is more oxidized than in the Meishan sediments. Grasby et al. (2017) attributed the differences in Δ199Hg MIF between these two sets of data to volcanic input in deep water marine environments for Buchanan Lake, while the near shore environment of deposition for Meishan have Δ199Hg isotopic signatures of soil and/or biomass input, and that the deep marine signature is overwhelmed in near shore locations due to Hg input from terrestrial sources. This shows that sediments forming in deep, open marine environments are likely to be more oxidized and contain more Hg2+. By contrast, sediments forming in near-shore, shallow marine environments, although more likely to have a higher terrestrial Hg input, are also more reducing, with the dominant form of Hg likely to be Hg0.

If the observed differences in slope on Δ199Hg versus Δ201Hg MIF plots are indeed controlled by the sediment redox state, then it is possible to test whether a relationship exists between fH2S, and the isotopic composition of Hg in such a sediment. Estimation of fH2S may be made using the equilibrium mineral-based model between iron chlorite, quartz, water and hydrocarbons, at any specified pressure and temperature. Model details and a work flow for its application is in Bryndzia and Villegas (2020), and will not be repeated here. The predicted fH2S for the gas condensate reservoirs in the CNS is shown in figure S3. The fH2S in figure S3 has been estimated at reservoir pressure and temperature, and is independent of the measured Hg isotopic composition. The fH2S model for hydrocarbons from the CNS in figure S3 shows a well-defined linear trend for enrichment in Δ199Hg as a result of decreasing fH2S i.e., oxidation. More importantly, the most reduced and most oxidized samples behave in a consistent manner for both MDF and MIF of Hg isotopes in these gas condensate reservoirs. The single outlier in figure S3 has an fH2S that is inconsistent with the rest of the gas condensate samples in this part of the CNS graben and is likely to have been derived from a deeper Triassic source.

Figure 9 shows the linear regression models for cinnabar ores from Terlingua, Monte Amiata, and Huancavelica, gas condensate reservoirs from the CNS, and Hg-enriched sediments from Zhijin, Meishan and Buchanan Lake (Grasby et al., 2017). The MIF slope for Meishan sediments (1.12 ± 0.32; 2σ), is similar to that of euxinic sediments from Zhijin (1.07) and euxinic sediments and coals (1.09 and 1.03, respectively). As indicated by the bold red arrow in figure 9, the data support the hypothesis that deviations in slopes of Δ199Hg/Δ201Hg from the trends for euxinic sediments and coals do correlate with oxidation i.e., reduction in fH2S. This is supported by the fact that in figure 9, the cluster of data from Buchanan Lake plots together with CNS-07, the most oxidized hydrocarbon sample from the CNS graben.

In general terms, the reservoir redox model supports the hypothesis that the slopes of Δ199Hg−Δ201Hg MIF plots reflect relative differences in redox state of Hg-enriched sediments, particularly in the domain of positive Hg MIF. However, the present data does not permit conclusive demonstration of this hypothesis for different types of sediment. This should be the focus of further research, and recent progress addressing this issue has been made by Frieling et al. (2023). The important observation demonstrated by figure S3 is that small variations in Δ199Hg MIF of Hg isotopes are to be expected as a result of natural variations in redox state for sediments deposited in different environments, such as open deep-marine versus shallow near-shore, as proposed by Grasby et al. (2017).

5. CONCLUSIONS

It is the ubiquitous generation of hydrocarbons from Hg- and organic-rich sediments that results in a dramatic increase in Hg enrichment in reduced hydrothermal fluids i.e., oils and brine, termed by numerous researchers as “hydrothermal petroleum”. Hg0(org) has relatively high solubility in hydrocarbon liquids as does Hg0(aq) in brines, and as recently demonstrated for the Terlingua Hg deposits in SW Texas, these are the principal ore-forming fluids responsible for the deposition of the giant cinnabar deposits in table 1.

MIF mercury isotope data for most cinnabar ores closely resembles the Hg isotopic composition of CFBs, and provides compelling evidence that Hg in most cinnabar deposits, globally distributed throughout geologic time, all share an original upper mantle origin for their Hg. MDF of mercury isotopes in cinnabar show that Hg was sourced from Hg-enriched sediments, some of which record globally significant LIP events and are associated with hydrocarbons generated from organic-rich source rocks and sediments, such as the OAE-2, NAIP, and ST LIPs, for example.

Hg isotopes confirm an upper mantle source for Hg in a suite of hydrocarbon source rocks in the CNS graben. The upper Jurassic Pentland coal and Kimmeridge shale both received their Hg endowment from the same Jurassic volcanic event that also generated conditions favorable for producing the organic-rich Kimmeridge black shale source rock. This is the first time that a mantle source has been shown to be the potential source of Hg in a suite of hydrocarbon source rocks in a major hydrocarbon producing province.

Significant depletions in 202Hg are observed in HP/HT gas condensates from reservoirs in the CNS graben, consistent with partitioning of 198Hg0(g) into a hydrocarbon gas phase during early diagenesis of organic-rich source rock shales. The volatilization of 198Hg0(g) is accompanied by early loss of labile H2S, and is independent of MIF of Hg isotopes.

Cinnabar in all deposits is unusually enriched in 202Hg relative to CFB, its nominal upper mantle source. There are two principal causes for the observed enrichments in 202Hg. One is due to significant loss of 198Hg0(g) resulting in a 202Hg enriched residual Hg pool, from which 202Hg-enriched liquid hydrocarbons and Hg0(org) were later generated. The other is caused by oxidation of coexisting Hg0(org), Hg0(aq), and H2S at the site of cinnabar deposition. This is the reason why the MDF trend of δ202Hg in the Hg ore minerals in the Terlingua and Monte Amiata deposits is similar to the δ202Hg isotopic enrichment trend observed in OAE-2 sediments from the type locality in Rehkogelgraben, Austria.

The Δ199Hg /Δ201Hg slope for hydrocarbons is 1.30 ± 0.24 (2σ) and is almost identical to that reported for photoreduction due to the MIE. The Δ199Hg /Δ201Hg slopes for cinnabar from Terlingua and Huancalevica are consistent with previously published experimental studies suggesting that MIF of Hg isotopes in cinnabar was due to the NVE.

The Almaden Hg deposits in Spain represent the largest enrichment of Hg on Earth. The age of the host sediments for these deposits is Silurian–Devonian, yet the unambiguous Hg isotope signature for these deposits (and the Indrija Hg deposits in Slovenia), are the PTB sediments associated with the Permian–Triassic Siberian Traps LIP, confirmed by the Pb isotope ages of cinnabar mineralization.

In the domain of positive MIF, deviations in Δ199Hg from linear trends for coals and euxinic sediments with Δ199Hg /Δ201Hg slopes of ~1, is due to variable redox conditions in the sediments, controlled by the relative proportion of reduced and organic-rich material in which the dominant form of Hg is Hg0, and oxidized tuffaceous sediments in which the dominant form of Hg is Hg2+. This hypothesis is supported by estimates of fH2S in CNS gas condensate reservoirs in which Δ199Hg is strongly correlated to fH2S.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

LTB is grateful to Shell International Exploration & Production Inc. for approving Release of Technical Data included in this paper, and to Associate Professor Ilia Rodushkin, Laboratory Manager, ALS Scandinavia AB, for providing details on Hg isotope analyses on hydrocarbons and subsurface rock samples used in this study.

This paper benefitted from reviews by Dr. Paul G. Spry, two anonymous reviewers, and the editorial guidance of Editor Dr. Mark Brandon and Associate Editor Dr. Timothy W. Lyons.

FUNDING

No external funding was associated with the research and writing of this paper

DATA AND SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION

https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.2547d7x5j

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

LTB designed and performed the research, analyzed the data, prepared the figures, wrote the paper and is wholly accountable for its content.

COMPETING INTEREST STATEMENT

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Editor: Mark T. Brandon, Associate Editor: Timothy W. Lyons

._also_plotted_are_hg_i.png)

_and_reservoir_rocks_from_the_cn.png)

_and_figur.png)

_mdf-mif_hg_isotope_data_for_hg_ore_minerals_from_terlingua_(sw_texas__solid_round_s.png)

_mdf-mif_hg_isotope_data_for_hgs_from_wanshan_and_paiting__and_maoshi_and_zhijin_cam.png)

_mdf-mif_hg_isotope_data_for_hgs_from_almaden_(spain)_and_indrija_(slovenia)__togeth.png)

._also_plotted_are_hg_i.png)

_and_reservoir_rocks_from_the_cn.png)

_and_figur.png)

_mdf-mif_hg_isotope_data_for_hg_ore_minerals_from_terlingua_(sw_texas__solid_round_s.png)

_mdf-mif_hg_isotope_data_for_hgs_from_wanshan_and_paiting__and_maoshi_and_zhijin_cam.png)

_mdf-mif_hg_isotope_data_for_hgs_from_almaden_(spain)_and_indrija_(slovenia)__togeth.png)