1. INTRODUCTION

Most of the world’s LREE supply (over 90%) is produced from four giant deposits: Bayan Obo, China; Mount Weld, Australia; Mountain Pass, USA; and Maoniuping, China. However, as demand increases and the largest resources become depleted, other small or moderate-sized carbonatite-hosted REE deposits may become important future producers. Additionally, some alkaline-carbonatite complexes show evidence of LREE-HREE fractionation and host HREE-dominant resources or occurrences (e.g., Lofdal, Namibia; Songwe Hill, Malawi; Salpeterkop, South Africa; Pivot Creek, New Zealand; and Huanglongpu, China; Broom-Fendley et al., 2021, and references therein).

Understanding the fate and transport of REEs in fluids associated with carbonatite intrusions is key to determining the processes responsible for ore-grade enrichments. Both magmatic-hydrothermal and external fluids can affect REE grade and tonnage in carbonatite-associated deposits (Verplanck et al., 2016). Experimental investigations show that fluids enriched in specific ligands are capable of fractionating REEs, potentially leading to district-wide zonation or areas enriched in lanthanides that have greater supply vulnerabilities.

Examination of the strength of REE complexes with various ligands (Cl-, F-, SO42-) in hydrothermal fluids has demonstrated that Cl- can be an efficient hydrothermal transport ligand of REEs, and due to the insolubility of fluocerite, F- is likely to induce REE precipitation rather than facilitate transport (Gammons et al., 1996, 2002; A. Migdisov et al., 2009, 2016; A. A. Migdisov & Williams-Jones, 2014; Williams-Jones, 2015; Williams-Jones et al., 2012). In some silica-undersaturated and peralkaline complexes hosting REE deposits, district-scale LREE-HREE zonation can be explained by the greater stability of LREE-chloride complexes and preferential hydrothermal transport of LREE to greater distances from the source (Williams-Jones, 2015; Williams-Jones et al., 2012). This model explains REE fractionation and mobility in peralkaline or granitic systems where fluids are acidic to near-neutral and Cl- concentration greatly exceeds that of other ligands. However, the model does not necessarily explain how REEs are transported in many of the world’s largest REE deposits, those that are associated with carbonatites where fluids may have concentrations of CO32-, HCO3-, F-, SO42-, or PO43-, exceeding Cl- by orders of magnitude.

A growing body of evidence shows that other ligands such as SO42- and hydroxyl-carbonate, or even alkalis can play an important role in the mobility of REEs in alkaline-carbonatite systems. For example, fluid inclusion studies of China’s carbonatite-related deposits at Dashigou (Cangelosi et al., 2020), Dalucao (Shu & Liu, 2019), and Maoniuping (Liu et al., 2019; Xie et al., 2009, 2015; Zheng & Liu, 2019) found that carbonatitic fluids or external fluids capable of REE transport are sulfate-rich. Experiments by Louvel et al. (2022) show that hydroxyl-carbonate complexes may effectively transport REEs in the alkaline fluids likely to be circulating in and around carbonatites, and that HREEs are mobile in such fluids at <300°C. Other studies demonstrate that in carbonatite deposits, LREEs are not transported great distances and instead early REE minerals experience in situ replacement, often upgrading the REE content of the carbonatite to ore grades (Anenburg et al., 2020, 2021; Yang et al., 2024). These authors have also advocated for enhanced LREE-HREE fractionation due to the greater solubility of specific alkali-dominated REE complexes.

In carbonatites, fluid inclusions are commonly found in calcite, fluorite, apatite, and occasionally in bastnäsite, monticellite, olivine, and zircon (Walter et al., 2021). Other attempts to characterize carbonatitic fluids have focused on quartzitic wall-rock or alkali silicates in associated fenites (Bühn et al., 2002; Bühn & Rankin, 1999; Liu et al., 2019; Williams-Jones & Palmer, 2002). Summarizing several previous carbonatite fluid inclusion studies (e.g., Bühn et al., 2002; Bühn & Rankin, 1999; Nesbitt & Kelly, 1977; Prokopyev et al., 2016; Rankin, 2005; Samson, Liu, et al., 1995; Samson, Williams-Jones, et al., 1995; Walter et al., 2020; Williams-Jones & Palmer, 2002), Walter et al. (2021) describes the four most common types of fluid inclusions in carbonatites: 1) vapor-poor H2O-NaCl fluids with up to 50 wt% salinity, 2) vapor-rich H2O-NaCl-CO2 fluids with <5 wt% salinity, 3) multicomponent fluids with high salinity and without CO2, and 4) multi-component fluids with high salinity and high CO2. Reconstruction of fluid compositions from fluid inclusions can present challenges in carbonatite samples. For example, the high salinity calculated for carbonatite-hosted inclusions is not controlled by NaCl abundance but rather complex (Na,K)SO4-(Na,K)CO3-(Na,K)Cl fluids commonly containing numerous carbonate and sulfate solids with or without halite. Quantitation by in situ methods (e.g., LA-ICP-MS) is complicated by the tendency of common host minerals to cleave during ablation (e.g. calcite and fluorite) and difficulty in isolating the inclusion signal from the signal of compositionally complex host minerals such as apatite (Walter et al., 2021).

Our goal was to reconstruct the physiochemical conditions under which early protore REE mineralization occurred in a moderate-size, carbonatite-hosted, REE resource in the Bear Lodge Alkaline Complex (BLAC) through the study of fluid inclusions. The BLAC was selected because our previous work enabled identification of appropriate samples to unravel the complex paragenesis. We compare the REE mineralizing fluids with those responsible for peripheral fluid-mediated smoky quartz and fluorspar occurrences across the complex. Classic microthermometry techniques are used to reconstruct homogenization temperatures (Th) and salinity. Petrography, microRaman spectroscopy, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) energy-dispersive spectroscopy (EDS), decrepitate mound analysis, and laser ablation inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (LA-ICP-MS) were used to examine multi-phase inclusions and determine the relative proportions of major ions in trapped fluids. Noble gas isotope analyses helped differentiate mantle and crustal inputs at different areas within the complex. Results are discussed in context with recent studies examining the importance of alkalis (Na, K), anions (SO42-, CO32-, F-, Cl-), fluid-melt immiscibility, and relationships with eruptive units to the fate and transport of REEs in alkaline-carbonatite complexes.

2. GEOLOGIC SETTING

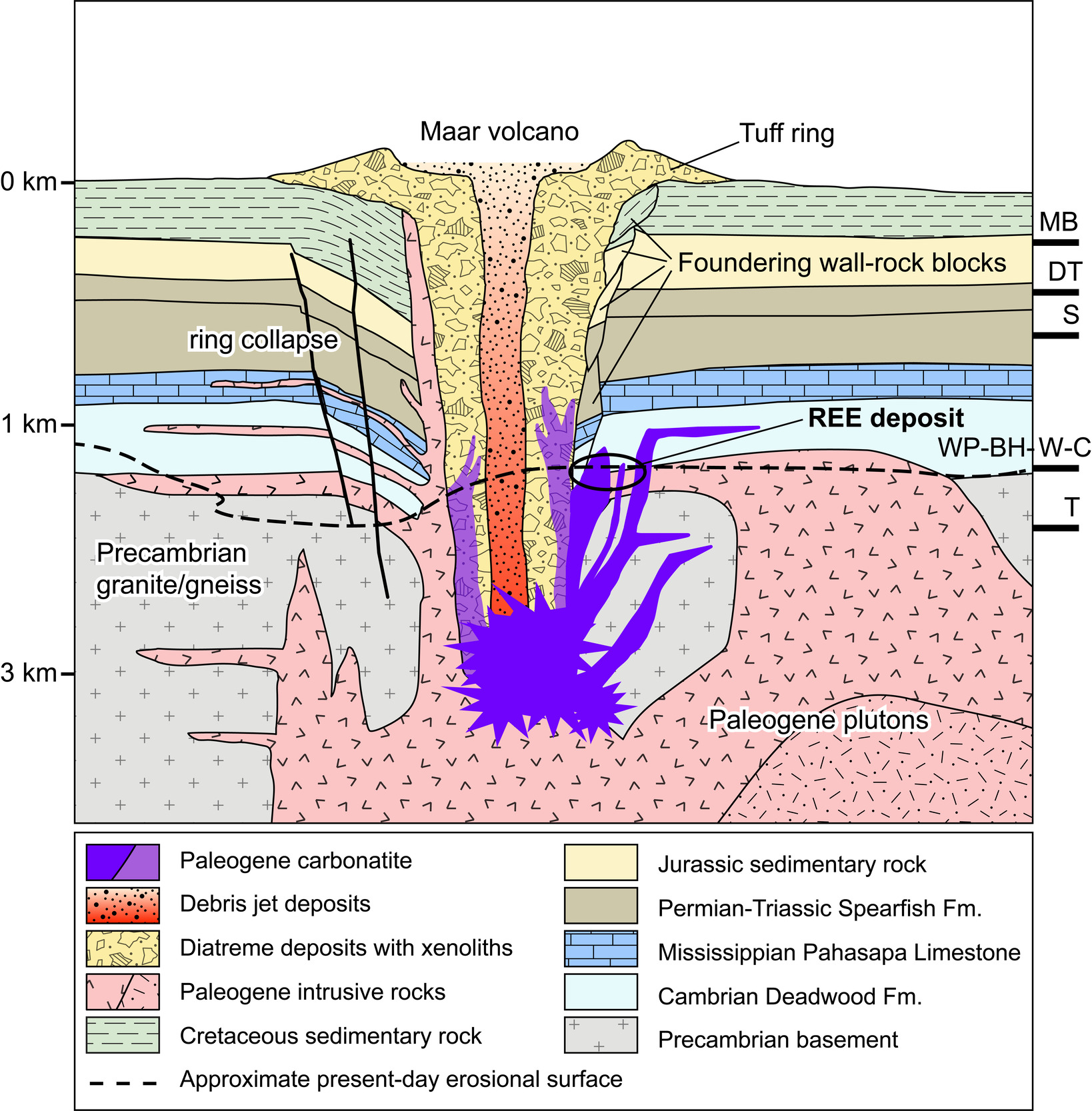

The BLAC is a bilobate composite laccolith located along a belt of Paleocene to Eocene intrusive centers in the northern Black Hills region of Wyoming, USA. Alkaline silicate and carbonatitic magmas intruded Archean granite and Paleozoic sedimentary rocks between 54 and 50.5 Ma (Mercer et al., 2022; C. M. Mercer, U.S. Geological Survey, unpublished data, 2025), forming the BLAC toward the northwestern end of this magmatic belt (fig. 1A, B). The magmas intruded as sills and other small, hypabyssal intrusions, substantially inflating the sedimentary section. Intrusions of phonolite, tephriphonolite/phonotephrite (nepheline syenite and malignite), latite, syenite, trachyte, pseudoleucite porphyry, carbonatite, and lamprophyre constitute the core of the subvolcanic complex (Andersen et al., 2019; Felsman, 2009; Jenner, 1984; Olinger, 2012; Verplanck et al., 2020). Pipes and dome-shaped masses of heterolithic diatreme breccia occur throughout the BLAC, most notably at Bull Hill, Carbon Hill, and Whitetail Ridge (fig. 1C). A carbonatite dike swarm and vein stockwork were emplaced near the coalescence of the northern and southern lobes. The weathered upper portions of the dikes host a measured and indicated resource of 6.02 million tonnes averaging 4.08 wt% total rare earth oxide (TREO) at a cut-off grade of 2.18% TREO (Noble et al., 2024).

Carbonatite emplacement depth is inferred from studies of the Black Hills uplift, known thickness of overlying strata, and erosion rates. The present erosional surface reveals, at roughly equal elevation, the oxidized carbonatite dike swarm, diatreme breccia pipes, and phonolitic sills in the lower Cambrian Deadwood Formation and along the Precambrian nonconformity (fig. 2). The roughly coeval Eocene diatremes and intrusions at Devils Tower and Missouri Buttes (25–30 km northwest of the BLAC) may have transected units as young as the Late Cretaceous Mowry Shale (Závada et al., 2015). Based on known thicknesses in the broader Black Hills region (Karner & Patelke, 1989), the Cambrian-to-Cretaceous sedimentary section by early Eocene would have been at maximum, ~1.5 km thick. Accompanying tectonism and domal uplift of the Black Hills during the Paleocene and early Eocene (Lisenbee, 1988), rapid erosion of the upper Cretaceous foreland sediments cut down to and perhaps through Paleozoic strata in the western portion of the uplift prior to intrusion of phonolitic magmas forming the BLAC (Fan et al., 2011; Smith et al., 2008; Závada et al., 2015). Therefore, all Cretaceous and at least some upper Paleozoic sediments are assumed to have eroded by time of intrusion. Additional evidence for the proximity between the present exposure level and the Eocene paleosurface includes the occurrence of volcanic facies—such as welded ash tuff—on Sundance Mountain, located 11 km south of the central Bear Lodge diatremes (Fashbaugh, 1979; Halvorson, 1980; Závada et al., 2015). Based on this collective evidence, we estimate an emplacement depth of ~1 km for central carbonatite intrusions of the BLAC (fig. 2).

Historical exploration activity in the BLAC focused on Au, Cu, Mo, REEs, U, thorium, and fluorspar. The size of the carbonatite-hosted REE resources at Bull Hill and Whitetail Ridge was recognized after extensive drilling campaigns started in 2004. In 2011, a NI 43-101-compliant gold resource of just under one million troy ounces was reported for three main Au-mineralized zones (Rare Element Resources Ltd., 2011). Approximately 43% of the resource (408,000 ounces) is hosted by a pseudoleucite porphyry breccia near Smith Ridge (fig. 1D). The igneous breccia pipe is an inverted conical shape, divided and offset by a left-lateral fault, with Au mineralization in both the east and west portions. Although no absolute ages are available for the pseudoleucite porphyry, the breccias penetrate large blocks of Precambrian granite and other alkaline intrusive rocks (fig. 1D), and, like the carbonatite dike swarm, are probably a later intrusive phase. The highest Au grades occur where the pseudoleucite porphyry body was subsequently brecciated by hydrothermal fluids resulting in a fluorite-matrix breccia with additional K-feldspar, barite, celestine, Fe oxide/hydroxides, clays, and drusy quartz.

Where the silica-undersaturated alkaline melts and/or fenitizing fluids interacted with Archean granite and Cambrian sandstones, silica remobilization is evident. A particularly good example of this process is exhibited by smoky quartz veins near the lower Cambrian-Precambrian contact at the Smith Ridge area (fig. 1D). Fenitization is recognized in the BLAC as K+-Fe3+ metasomatism or K-feldspar+pyrite±biotite alteration and commonly manifests as an overall K2O increase through feldspathic recrystallization of alkaline silicate rock matrix (Felsman, 2009). Felsman (2009) also noted sodic-style fenitization at the Carbon Hill area which is more deeply eroded and hosts coarser-grained foid syenite and carbonatite dikes, consistent with alkali zonation observed in other carbonatite complexes (Elliott et al., 2018; Le Bas, 1981; Woolley, 1982).

3. SAMPLE SELECTION AND DESCRIPTIONS

The principal REE resource in the BLAC occurs near surface down to ~120 m depth within complete to partially oxidized and leached carbonatite dominated by Ca-REE fluorcarbonate minerals (bastnäsite, parisite, synchysite), and lesser REE phosphates and cerianite (Andersen et al., 2017; Dahlberg et al., 2014; Moore et al., 2015). An upward increase in total REE content corresponds to replacement of REE-Sr-Na carbonates (ancylite, carbocernaite, and burbankite) by Ca-REE fluorcarbonates, coincident with increasing sulfide oxidation and increasing carbonate dissolution (Andersen et al., 2017; Hutchinson et al., 2022). These modifications are thought to be the result of low-T (<250°C) alteration by fluids with low CO2/H2O ratios, high fluid/rock ratios, and an increasing proportion of meteoric water. Minerals formed in the shallow, oxide zone were not conducive to fluid inclusion studies. Thus, the fluids examined here likely precede the postmagmatic fluid alteration events involved in transforming carbonatite from simply “REE-enriched” to “REE ore.” Our sampling effort focused on rocks that escaped near-surface, ore-grade enrichment and instead contain evidence of early-stage REE mineralization and possible effects of orthomagmatic fluids (Group 1 carbonatites of Andersen et al., 2019) as described in other carbonatite fluid inclusion studies (e.g., Bühn & Rankin, 1999; Rankin, 2005; Samson, Liu, et al., 1995; Samson, Williams-Jones, et al., 1995; Walter et al., 2021). Samples were collected from four areas described in the following sections.

3.1. Central REE-bearing carbonatite dikes and veins

Drill core samples (BL10-11, BL10-07, BL10-30, BL10-32, S121-945, R11-32-377 and WBD-10-475), were selected from the central carbonatite dike swarm and vein stockwork near the Bull Hill, Whitetail Ridge, and Carbon Hill diatremes (fig. 1C). Carbonatite samples containing fluorite were selected because the fluorite contains larger, well-preserved inclusions and multiple generations of fluorite and calcite could be examined (fig. 3A–F). Bear Lodge carbonatite textures are heterogeneous, and calcite textures in the studied samples are grouped broadly as coarse-grained, fine-grained, and late-stage rhombic calcite (fig. 4A–C). Calcite recrystallization is observed around REE pseudomorphs, many of which exhibit rims of calcite displaying flat or HREE-enriched chondrite-normalized REE patterns and positive δ18O shifts (Chakhmouradian et al., 2017; Olinger, 2012). Fluorite occurs in veins, stringers, and irregular masses that are paragenetically earlier or equivalent to calcite (fig. 3A-F).

Carbonatite samples containing fluorite commonly contain paragenetically early REE minerals (e.g. burbankite, calcioburbankite, carbocernaite). Some samples have δ13C values (-7.6 to -8.5 ‰) and δ18O values (8.6 to 11.4 ‰) that are typically considered representative of primary igneous carbonate (or close to primary) and fall within the Group 1 Bear Lodge carbonatite field of Andersen et al. (2019). These samples from the central carbonatite dike swarm provide the best opportunity to characterize early REE-bearing fluids.

3.2. Smith Ridge pseudoleucite porphyry breccia

Although the pseudoleucite porphyry breccias at Smith Ridge are recognized as a gold resource, this site was selected because of its proximity to the central REE-rich carbonatite dike swarm (1.5 km; SMCF samples; fig. 1B, D) and the presence of matrix fluorite, likely to host inclusions. The interstitial purple fluorite is extraordinarily dark and exhibits growth zoning (fig. 5A–C). Primary fluid inclusions were identified in reference to these growth zones (fig. 5C).

3.3. Smith Ridge smoky quartz veins in Cambrian-Ordovician quartzites

Smoky quartz veins hosted by Cambrian to Ordovician quartzites exposed on Smith Ridge were sampled near the fluorite-matrix pseudoleucite porphyry breccias (SSQ samples; figs. 1D and 5D). Archean granite at Smith Ridge and throughout the BLAC is desilicated (voids where quartz was removed), particularly in proximity to SiO2-undersaturated alkaline intrusions, and this type of silica remobilization may have produced the network of cm-scale recrystallized quartz veins in the quartzite. Veins are composed of both colorless and smoky quartz varieties, commonly zoned with smoky quartz at wall-rock contacts to colorless quartz cores, some containing open space at the center. Samples examined in this study were exclusively of the smoky quartz variety and display growth zoning in cross-section (fig. 5E). Primary fluid inclusions and zones of decrepitated primary inclusions were identified in reference to these growth zones (fig. 5F). A similar approach of studying carbonatite-derived fluids was employed by Bühn and Rankin (1999) who analyzed inclusions in quartzitic country rocks of the Kalkfeld carbonatite complex, Namibia.

3.4. Peterson Claims fluorite-filled lenses and breccias in limestone

Fluorite-filled fissures and bedding replacement deposits in the Mississippian Pahasapa Limestone were sampled 2.7 km outward (west) from the central carbonatite dike swarm (fig. 1B; sample 12BL33). Samples were collected from prospect pits and waste piles near exploratory shafts that were excavated after fluorspar discovery in 1943 (Dunham, 1946; Haff, 1944; U.S. Bureau of Mines, 1944). The fluorspar ore consists of brecciated and massive dark-purple fluorite associated with calcite, fine-grained quartz, K-feldspar, and unreplaced limestone breccia (Dunham, 1946). Unlike the sites above, there are no known REE, thorium, or Au anomalies associated with these fluorspar occurrences.

4. ANALYTICAL METHODS

4.1. Petrography and cathodoluminescence

Petrography was performed on 100-µm thick doubly polished sections using Olympus BX50 and BX53M transmitted light microscopes. Fluid inclusion assemblages were identified based on the criteria of Chi et al. (2021) and Goldstein and Reynolds (1994). Estimates of the relative volume of liquid, vapor, and solid phases were made based on visual estimation at room temperature and may vary from actual values by ±10% (Bakker & Diamond, 2006). Textural relationships of minerals in thick sections and duplicate thin sections were investigated using a cold-cathodoluminescence (CL) system designed by Relion Industries coupled to a Nikon Optiphot transmitted light microscope and fitted with a Leica DFC7000 T digital camera at the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) in Spokane, Washington. The CL system was operated under vacuum at 6–10 kV. Images and results from all analytical methods are provided in Olinger et al. (2025), available at https://doi.org/10.5066/P1TTX78H.

4.2. Raman spectroscopy

Laser Raman spectroscopic analyses were performed using a Horiba LabRAM HR Evolution Spectrometer housed at the University of Colorado at Boulder. The instrument was operated using a 100 mW 532 nm (green) wavelength, frequency-doubled Nd:YAG laser source and a spot size of 1 μm for most analyses of inclusion-hosted solid, liquid, and vapor phases. The following settings were used for analysis of vapor, liquid, and solid phases, respectively: 1) 1800 grating, 1100–3000 cm-1 range, two increments at measuring time of 60 s each; 2) 600 gr/mm grating, 100–3000 cm-1 range, three increments at measuring time of 20 s each; and 3) 600 gr/mm grating, 100–1800 cm-1 range, three increments at measuring time of 20 s each. Additional analyses were performed using an Xplora Raman spectrometer housed at the USGS Denver Inclusion Analysis Laboratory (DIAL) with similar analytical settings. Spectroscopic analysis was performed on inclusions following petrography and prior to microthermometry. Phase identification was unsuccessful in most calcite-hosted inclusions and some fluorite-hosted inclusions due to fluorescence of the host using both 532 and 785 nm lasers. Raman spectra were processed using Horiba LapSpec 6 software (http://www.horiba.com/labspec6), and solid phases were identified by comparison with spectra from the RRUFF database (https://rruff.info/). Inclusions were analyzed for characteristic peaks of CO23- and SO42- as identified by Burke (2001) and Frezzotti et al. (2012).

4.3. Laser ablation ICP-MS

Solute-rich inclusions were analyzed by LA-ICP-MS to confirm the presence of suspected elements and inclusion components determined by laser Raman. Calcite-hosted fluid inclusions were analyzed using a Coherent GeoLas 193 nm ArF laser coupled with a Perkin Elmer NexION ICP-MS (Longerich et al., 1996). Settings for the performance check and experiment are provided in the accompanying data release: Olinger et al. (2025). The program, LADR (version 1.1.0720211123; Norris & Danyushevsky, 2018; http://norsci.com/ladr/) was used for data reduction. Reference glasses NIST 612 and BCR-2G were used as external standards. Sodium was used as the internal standard for the quality control check on reference glass, GSD-1G.

4.4. Microthermometry

Microthermometry was conducted at the USGS DIAL using a Linkam TMSG600 stage with a Linkam T96-S system controller mounted on an Olympus BX60 microscope with a PointGrey GS3-U3-28S5C-C camera. Temperature ramp profiles were controlled using the LINK software (version 1.1.1.5; https://www.linkam.co.uk/link). Temperature calibration was performed using SynFlinc fluid inclusion standards that covered a range of temperatures. Precision of measurements was ±0.3°C for melting temperatures and ±3.0°C for homogenization temperatures. The complexity of trapped fluids limited salinity calculations to percent NaCl equivalent using the formula of Bodnar (1993) for the system NaCl-H2O. Pressures, compositions, and equivalent salinities were calculated for liquid-vapor (LV) inclusions containing both CO₂(v) and CO₂(l) in the H₂O–CO₂–NaCl fluid system using the program provided by Steele-MacInnis (2018), and for CO₂-poor LV inclusions in the H₂O–NaCl fluid system using the HOKIEFLINCS_H₂O–NaCl program from Steele-MacInnis et al. (2012).

For inclusions that did not homogenize at ≤450°C, sample chips were transferred to a USGS-type gas-flow heating stage (Goldstein & Reynolds, 1994) with a maximum operating temperature of 800°C. The gas-flow stage, coupled to a Nikon Optiphot transmitted light microscope, was calibrated using an ice bath (±0.3 °C accuracy for ice melting temperatures) and the SynFlinc fluid inclusion standard for homogenization temperatures (±3.0 °C precision). Most inclusions reached complete homogenization using one of the two stages, and rare examples decrepitated prior to complete homogenization.

4.5. Decrepitate mound analysis

Decrepitate mounds were analyzed by EDS to check for the presence of other ions not identified by microRaman spectroscopy and to evaluate in a general sense the variable proportions of cations and anions in fluorite- and smoky quartz-hosted fluid inclusions. Mounds were produced by rapidly heating 100-μm thick sample chips using the gas-flow heating stage and were observed with a transmitted light microscope. Samples were loaded onto a Si wafer and were topped with a fragment of another Si wafer to capture any residues that decrepitated near the top surface. Silicon wafers and sample chips were cleaned with acetone prior to loading in the chamber and nitrile gloves were worn to reduce the possibility of salt transfer. Initial trials showed inclusion deformation or host mineral dissolution was possible at high temperatures if heated slowly and decrepitation did not always occur upon approach to maximum stage temperatures. Therefore, samples were rapidly heated (<180 seconds), and inclusions decrepitated between 450 and 700°C. After decrepitation, sample chips and Si wafers were placed on a glass slide with carbon tape, carbon-coated within an hour, and loaded into an SEM. Qualitative analysis of decrepitate mounds was performed using an FEI SEM at the USGS Denver Microbeam Laboratory.

4.6. Bulk leachate noble gas isotope analysis and test for CO2

Noble gases (Ar, He, Ne) in fluorite- and quartz-hosted fluid inclusions were analyzed following the method outlined in Landis and Hofstra (2012) and references therein. Gases were extracted by thermal decrepitation followed by analysis using a high-resolution sector mass spectrometer (MAP 215-50) at the USGS Noble Gas Laboratory in Denver, Colorado. Mineral separates (0.5 to 1.5 g) were drop-loaded into a preheated evacuated vacuum furnace, heated to 350°C, and held at temperature for 10 to 30 minutes to collect volatiles for analysis. Reactive gases were chemically removed from the gas mixture and the remaining noble gases were cryogenically separated (liquid nitrogen trap at -196.15°C and helium refrigerant trap at -263.15°C) prior to sequential determinations of noble gas abundance and isotopic compositions.

Separate sample splits and wafers were crushed while immersed in kerosene to test for the presence of CO2 following the methods outlined in Diamond and Marshall (1990) and Goldstein and Reynolds (1994). When bubbles are observed in the kerosene during crushing, it is assumed that CO2 was present in the inclusion(s).

5. RESULTS

5.1. Fluid inclusion populations from petrography and Raman spectroscopy

Four main types of fluid inclusions were found in calcite, fluorite, and smoky quartz: 1) liquid-vapor (LV) inclusions where vapor bubbles commonly constitute 60–95 vol.% of the inclusions found in both calcite and fluorite, 2) liquid-vapor-solid (LVS) inclusions commonly containing multiple daughter crystals found in fluorite, calcite, and smoky quartz, 3) fluorite-hosted “double bubble” inclusions containing large CO2 vapor bubbles with outer rinds of liquid CO2 (LVC), and 4) calcite-hosted, liquid-dominant L90V10 inclusions. Crystal-packed inclusions, with little or no visible fluid other than a bubble were also observed (fig. 6A). These are similar to the salt melt inclusions (type V) of Walter et al. (2021) and described previously by Nesbitt and Kelly (1977), Prokopyev et al. (2016), and Rankin (2005). The observed populations are summarized in table 1 with locality, host mineral, primary-secondary designation, phase proportions, and daughter minerals. These populations are discussed in the following sections.

5.1.1. Bull Hill carbonatites: calcite

Inclusion populations in three different calcite textures were examined: fine-grained, coarse-grained, and late-stage rhombs (fig. 4A–C). Fine-grained calcites contain LV inclusions with large vapor bubbles, some containing >80 vol.% vapor (table 1, fig. 6B). Based on their isolated position in calcite cores and lack of recrystallization textures, these inclusions are characterized as primary. Vapor-dominant inclusions are also present in secondary trails cutting across the calcite grains. Aqueous SO42- and trace CO2 were detected in some inclusions by laser Raman spectroscopy. Fine-grained calcite contains few mineral inclusions but, if present, are burbankite.

Coarse-grained calcite is dominated by solid inclusions of apatite, barite/celestine, burbankite, and to a lesser extent ancylite, with intact fluid inclusions being comparatively rare. These are liquid-dominant (~90 vol.% liquid) secondary and pseudosecondary LV inclusions. Pseudosecondary fluid inclusion populations restricted to calcite cores are composed of irregularly shaped inclusions (fig. 6C) associated with abundant empty cavities (decrepitated inclusions). Secondary LVS inclusions containing multiple daughter minerals were observed only in fracture-filling calcite and veinlets cross-cutting coarse-grained calcite. These LVS inclusions resemble those found in inclusion poor fluorite (see 5.1.2. Bull Hill carbonatites: fluorite).

Rhombic calcite is distinctly later than other calcite generations as some rhombs partially fill open space of REE pseudomorphs or vugs (fig. 4C), equivalent to the “Calcite-2” of Chakhmouradian et al. (2017). Inclusions are isolated to crystal cores and these liquid-dominant (~90 vol. % liquid) LV populations are classified as primary. Liquid-vapor inclusions hosted in both coarse-grained and rhombic calcite lack detectable SO42- and CO2.

5.1.2. Bull Hill carbonatites: fluorite

Two main types of fluorite were consistently identified in multiple carbonatite samples from different areas of the dike swarm (samples R11-32-277A, BL10-32A, WBD10-475A; figs. 1C, 3, 7A). The two stages of fluorite are distinguished by their contained fluid inclusion populations and their color. Early, inclusion-rich (EIR) light purple fluorite is clouded by abundant secondary and pseudosecondary LV inclusions with large vapor bubbles and fewer secondary LVS inclusions with detectable SO42- in the aqueous phase and CO2 in the vapor phase (fig. 7A). Arrays of LV inclusions are never observed cross-cutting from early into late fluorite, supporting their classification as pseudosecondary.

Late, inclusion-poor (LIP) dark purple fluorite contains a population of LVS secondary and pseudosecondary inclusions with multiple solid phases (fig. 7B–E). Large nahcolite (NaHCO3) daughter crystals are ubiquitous in this population (fig. 8A). Other solids identified by Raman spectroscopy include equant, high relief alkali sulfates (thénardite, aphthitalite, arcanite?), Sr-bearing minerals (strontianite and celestine), and spicule- or rod-shaped burbankite/calcioburbankite (table 1; fig. 8B–D). Sulfate (SO42-) was regularly detected in the aqueous phase (fig. 8E), and HCO3- was measured in some samples. Minor CO2 was detected in some vapor bubbles. Burbankite (+calcioburbankite?) crystals are a common component within inclusions of this LVS population, though they are also abundant as solid mineral inclusions, commonly among the arrays of fluorite-hosted LVS inclusions (fig. 9A, B). Variability of the spectra may be due to a wide range of Na:Ca:REE, a feature also noted for inclusion-hosted burbankite by Bühn et al. (1999).

A less abundant but equally important inclusion population observed in both fluorite stages contains aqueous liquid with a CO2 vapor bubble surrounded by an outer rind of liquid CO2 (fig. 7F), referred to herein as LVC inclusions. In some LVC inclusions, the “double bubble” feature is visible at room temperature; whereas in others, the liquid CO₂ rim appears only upon cooling slightly below room temperature. Some LVS inclusions rarely contain visible liquid CO2 in the vapor bubble and are here designated LVS(C) inclusions. Calcite crystals observed in this inclusion population may be “accidental” trapped solids because complete homogenization was not achieved during heating experiments.

5.1.3. Smith Ridge fluorite-matrix breccia

Matrix fluorite in the Smith Ridge gold-bearing pseudoleucite porphyry breccias hosts primary inclusions along growth zones (fig. 5C). These inclusions are typically liquid-dominant, LVS inclusions, with solids occupying up to 40 vol.%. Nahcolite is the main daughter mineral and where additional solids were observed, they were typically calcite and alkali sulfate minerals. Sulfate peaks were detected in the aqueous phase and CO2 was absent. Primary LVS inclusion populations in Smith Ridge fluorite-matrix breccias have phases (liquid, vapor, nahcolite, sulfate) and phase ratios that are very similar to secondary and pseudosecondary populations in LIP fluorite from the Bull Hill carbonatites (table 1).

5.1.4. Smith Ridge smoky quartz veins

Smoky quartz veins at Smith Ridge contain primary LVS inclusions trapped along growth zones that commonly display doubly terminated negative crystal shapes (fig. 5F). Other, distinct growth zones contain fields of decrepitated inclusions (fig. 5E). Inclusions in smoky quartz are typically liquid-dominant, with solids comprising 20–40 vol.%. Nahcolite is the main daughter mineral (fig. 8F), and small equant crystals of alkali sulfate or barite are usually minor or absent. Sulfate was detected in the aqueous phase, and CO2 was absent in the vapor phase. As in the fluorite-matrix breccias, phase ratios and daughter crystals in these primary inclusions closely resemble those of secondary inclusions in the central carbonatites (table 1).

5.1.5. Peterson Claims fluorite-filled lenses and breccias

Zoned fluorite from prospects in the Mississippian Pahasapa Limestone exhibits well-developed growth zones with abundant primary inclusions, similar to those in fluorite from Smith Ridge. Early, core-confined zones contain primary populations of negative crystal-shaped LVS inclusions. Successive zones host LVS inclusions with fewer solids progressing to late outer zones containing only LV inclusions. Laser Raman analyses of these inclusions were unsuccessful due to high fluorescence of the host fluorite.

5.2. Laser ablation ICP-MS

Compositional data were acquired on select LVS inclusions via LA-ICP-MS to confirm the presence of REEs likely in the form of burbankite/calcioburbankite daughter crystals. Time-resolved spectra for several targeted inclusions show obvious inclusion signals characterized by the sudden increases in Na, K, Sr, and LREEs (fig. 10A, B). The LA-ICP-MS profiles capture the total contents of inclusions that commonly contain nahcolite, celestine, burbankite, and the aqueous and vapor phases.

5.3. Microthermometry

All uncorrected homogenization temperatures and pressures represent the minimum conditions at which fluids were trapped as a single homogeneous phase (fig. 11). For fluid inclusion populations in Bear Lodge samples that are represented by more complex systems (e.g., H2O-Na-K-Sr-HCO3-SO4-Cl), pressures and compositions should be considered approximate. Homogenization temperatures of vapor-dominant inclusions are also subject to greater uncertainty owing to the difficulty in detecting final disappearance of the liquid meniscus during heating (Bodnar, Burnham, et al., 1985; Bodnar, Reynolds, et al., 1985; Klyukin et al., 2019; Sterner, 1992).

5.3.1. Bull Hill

In Bull Hill carbonatite samples, fine-grained calcite hosts CO2-bearing LV and V inclusions with relatively high homogenization temperatures from 320°C to 432°C (fig. 11). Similar LV inclusions in EIR fluorite homogenize between 260°C and 391°C and have calculated pressures of 217–411 bars at homogenization. Salinity for this population of LV inclusions is approximately 2 wt.% NaCl equivalent, and CO2 concentrations are ~9 mol%. Eutectic temperatures of LV inclusions in EIR fluorite ranged from -29°C to -27°C. Because LV inclusions hosted in fine-grained calcite and EIR fluorite are paragenetically early and display a narrow range of homogenization temperatures, they likely represent the hottest stages of the system at lithostatic pressure.

LVS inclusions hosted in LIP fluorite show a wide range of homogenization temperatures and behaviors. Many homogenize by the disappearance of vapor phase between 138°C and 392°C, however higher temperature LVS inclusions often homogenize by dissolution of the last solid phase, with acicular minerals occasionally persisting to 556°C or higher (fig. 11). In the LVS inclusions, nahcolite dissolves at 103.1–185.8°C, and sulfate solids dissolve at 223.4–270.4°C. Ice melt temperatures in LVS inclusions range from -13.4°C to -6°C and eutectic temperatures were observed from -31.5°C to approximately -21°C. LVC double bubble inclusions in LIP fluorite have homogenization temperatures ranging from 266°C to 404°C, with homogenization of the two CO2 phases to CO2(l) at approximately 31.1°C. Salinities of 1–2 wt.% NaCl equivalent, CO2 concentrations of 33 mol%, and pressures at homogenization between 574 and 916 bars were determined for this LVC population. Two other LVC inclusion assemblages exhibited homogenization of the two CO2 phases to CO2(v); however, exact homogenization temperatures were not observed.

Late, LV inclusions hosted in coarse-grained calcite have Th from 143°C to 182°C with a few homogenizing below 130°C (fig. 11). Ice melt temperatures (Tmice) for these inclusions straddle 0°C, with most ranging from -3.8°C to -0.3°C, and some within the same assemblage reaching 5°C. Inclusions with Tmice above 0°C showed bubble disappearance during freezing, a disequilibrium behavior that prohibits calculation of fluid salinities. Eutectic temperatures for coarse-grained calcite LV inclusions range from -25.5°C to -15°C. In rhombic calcite, late LV inclusions have Th from 117°C to 158°C and Tmice from -2.8°C to -2.1°C, with ice persisting in some inclusions up to 3.8°C. These low-temperature LV inclusions have uncorrected pressures at homogenization between 4 and 8 bars, and salinities of 1–6 wt.% NaCl equivalent.

5.3.2. Smith Ridge

In zoned fluorite from Smith Ridge, LVS inclusions experienced nahcolite daughter crystal dissolution from 130°C to ~186°C with two inclusions showing disappearance of solids below 111°C. A few inclusions contained a second solid phase, calcite, which did not homogenize up to 265°C. Most inclusions in zoned fluorite reached total homogenization by vapor disappearance from 164°C to 274°C. Ice melt temperatures for the inclusions ranged from -9.7°C to ~0.0°C. Eutectic temperatures were observed from -29.8°C to -25.2°C.

Multiphase LVS inclusions hosted in smoky quartz from Smith Ridge homogenized by vapor disappearance between 108°C and 277°C. A few inclusions homogenized by solid dissolution, with Th between 92°C and 307°C. Nahcolite dissolved between 147°C and 180°C, and Tmice ranged from -11.5°C to -7.4°C. Eutectic temperatures were observed for a few inclusions at -26.5°C.

5.4. Decrepitate Residues

Decrepitated residues formed as circular mounds with conical centers (20–50 μm), trails (up to 60 μm in length), slug-shaped salt mounds, thin precipitate aprons, and opened inclusions with oblate or irregular shaped precipitates nearby. Decrepitation of LIP fluorite from carbonatite resulted in sulfate-dominant mounds often circular in form with a conical center. Several mounds were comprised of a Na-sulfate (thénardite/mirabilite) apron surrounding a Na+K±Sr sulfate central cone (fig. 12A, B). Analyses show that Na, Sr, and K are the dominant cations with trace amounts of Ca, Ba, and Ce. With abundant Ca in the fluorite substrate, it was difficult to confirm the presence of Ca in the residues. However, analyses showing detectable Ca and S, coupled with the absence of F on fluorite or Si wafer substrates, indicate the presence of Ca-sulfate (anhydrite or gypsum) in some residues. Several decrepitates were zoned from a celestine center to an outer anhydrite/gypsum apron (fig. 12C, D). (Na,K)Cl decrepitates were much less common than those dominated by sulfates and mixtures were also present (fig. 12E, F).

Growth-zoned fluorite and smoky quartz from the Smith Ridge area produced decrepitate mounds dominated by (Na,K)Cl salts and lower sulfate volumes. Spectroscopic analysis of primary inclusions in these samples showed phase ratios and daughter crystals (nahcolite and alkali sulfates) similar to secondary inclusions in LIP fluorite from the central Bull Hill carbonatites, but the mounds are markedly more Cl-rich. This suggests that Cl was concentrated in the aqueous phase and that the fluids captured in quartz and fluorite of the peripheral Smith Ridge locality may be more Cl-rich, though not at concentrations sufficient to form halite.

The decrepitate results suggest that Na is retained during heating and dissolution of nahcolite while the bicarbonate is lost during devolatilization as CO2 and water vapor. Sodium (and K) re-combine with Cl from the aqueous phase or SO42- from the sulfate daughter crystals and sulfate in the aqueous phase to form decrepitates of NaCl or alkali sulfates, respectively. It is possible that the gypsum/anhydrite in decrepitate mounds may acquire some Ca from the host fluorite during heating.

5.5. Bulk leachate noble gas isotope analysis

The multiple generations of secondary fluid inclusions in fluorite hindered isolation of mineral grains containing only a single inclusion population. However, because multi-phase inclusions were mainly confined to LIP fluorite and vapor-dominant LV inclusions were much more abundant in EIR fluorite, an effort was made to isolate the two fluorite generations for isotopic analysis. Concentrically zoned fluorite and smoky quartz grains from Smith Ridge were also separated and analyzed because they contain primary inclusions from a different area of the complex. Molar abundances and isotopic ratios of noble gases for fluorite and smoky quartz separates are reported in table 2 (Olinger et al., 2025).

Isotopic ratios of Ar (38Ar/36Ar and 40Ar/36Ar) and Ne (20Ne/22Ne and 21Ne/22Ne) are close to those of atmospheric values (table 2). The He/Ne and He/Ar values are approximately three orders of magnitude higher than air, which indicates a different, non-atmospheric source for He compared to Ne and Ar. The isotopic composition of He in the leachates can be interpreted in terms of crustal (R/RA: 0.02) and mantle (R/RA: 8) sources (Hofstra et al., 2016; Ozima & Podosek, 2001). Two fluorite samples from the central carbonatite dikes (R-11-32-377A: LIP fluorite and R-11-32-377B: EIR fluorite) have 3He/4He R/RA consistent with a MORB-like component (fig. 13). The EIR fluorite with abundant vapor-dominant inclusions derives 50% of its He from a MORB-like source. The Smith Ridge smoky quartz and breccia matrix fluorite separates have a much more crustal He source signature with R/RA of 0.1 and ~0.01, respectively. The spread of samples in figure 13 indicates that He is derived from a mixture of MORB-like and radiogenic sources. Collectively, the He, Ne, and Ar isotope results suggest that the dominant source of Ne and Ar is air-saturated groundwater into which magmatic vapor containing CO2 and He condensed.

6. DISCUSSION

6.1. Fluid types in the central carbonatites

Based on our results, we established a paragenesis for major fluid types in the central carbonatites, shown schematically in figure 14. In carbonatite dikes and veins, LV and V inclusions in fine-grained matrix calcites record higher Th (~320–450°C) compared to inclusions in coarse and rhombic calcites (~125–180°C) (fig. 11). The higher temperatures likely reflect an early stage of high-temperature calcite formation that was not subjected to later recrystallization, as indicated by the presence of enclosed burbankite mineral inclusions. This range of Th for fine-grained calcite inclusions broadly overlaps with the range observed for LV inclusions in EIR fluorite (~200–400°C), which formed later than the fine-grained calcite but prior to the LIP fluorite. Inclusions in these early minerals are mostly vapor-dominant and contain H2O with dissolved SO42- and CO2(v). The high 3He/4He R/RA mantle source component of the EIR fluorite LV inclusions lends further support to their classification as early, magmatic fluids (fig. 13).

Crystal-rich LVS inclusions containing nahcolite, alkali-sulfates, and burbankite represent an intermediate stage (fig. 14) because of their secondary nature in coarse-grained calcite, EIR fluorite, and LIP fluorite wherein they are the main inclusion type. This fluid is best described as a REE+Sr-bearing alkali bicarbonate-sulfate brine or brine-melt with H2O>HCO3>SO4>Cl. Solid inclusions of apatite, barite/celestine, and burbankite in coarse- and fine-grained calcite, along with the secondary LVS inclusions in coarse-grained calcite, suggest that both calcite types formed early in the paragenesis. The relatively high Th of LVS inclusions (556°C or higher in some) may be an indication of their early formation, as these temperatures greatly exceed those of inclusions measured in early fine-grained calcite. These high homogenization temperatures are close to or exceed some reported carbonatite melt temperatures, though they may not represent true trapping conditions.

Attempts to homogenize similar multi-solid inclusions from various carbonatites have been largely unsuccessful, even to temperatures up to 800°C (Rankin, 2005 and references therein). Complete homogenization may be hindered by the retrograde solubility displayed by minerals like thénardite and anhydrite, which are particularly common in the multiphase LVS inclusions. Incomplete homogenization may also be an indication of accidental entrapment of solid phases or necking during maturation of the inclusions, further complicating the interpretation of homogenization temperatures. Post-entrapment re-equilibration of fluorite-hosted inclusions must also be considered, as fluorite is a relatively weak host mineral in which inclusions can re-equilibrate with only minor overheating beyond their homogenization temperature (Bodnar & Bethke, 1984; Rowan, 1985). The observed variability in homogenization behavior and temperature may result from reheating of trapped fluids during multiple episodes of intrusion or fluid overprinting. Dissolution of the host mineral during analysis can also result in volumetric and compositional changes, thus affecting the solubility of daughter minerals and shifting the observed Th. The CaSO4 observed in decrepitate mounds requires a source of Ca, which was not detected in most inclusions; thus, some Ca may have been released from the fluorite host during gas-flow heating.

Rhombic calcite hosts LV inclusions that exhibit lower vapor proportions, lower salinity, and lower Th (~120–160 °C) compared to those in fine-grained calcite. These data, coupled with the positive δ18O shifts reported for this calcite type (Chakhmouradian et al., 2017), may indicate circulation of diluted magmatic fluids or the incipient influx of meteoric water (fig. 14). Coarse-grained calcite hosts inclusions with similarly low vapor:liquid proportions and a similar Th range (143–182°C). These inclusions are found among arrays of decrepitated inclusions suggesting post entrapment modification and re-equilibration due to changes in pressure and temperature (Zhang & Audétat, 2023). Because the coarse-grained calcite retains early primary mineral inclusions (burbankite), we suggest that coarse calcite was an early phase with some of the vacuoles reset later (without recrystallization) by the same late stage, low-T fluid captured in rhomb calcite (fig. 14).

6.2. Pressure estimates and phase separation

Homogenization pressures between 574 and 916 bars calculated for LVC inclusions in the H2O-CO2-NaCl system equate to an uncorrected paleodepth of 2.2–3.5 km at lithostatic pressure, greater than the ~1 km estimated depth based on the thickness of overlying strata in the BLAC during the Eocene (fig. 2). This estimated paleodepth is based on the widespread and rapid erosion of Cretaceous foreland sediments that is thought to have occurred prior to Eocene alkaline magmatism (Závada et al., 2015). If the entire Paleozoic section were present as well as major portions of the Cretaceous strata, the depth of emplacement may have been 500–1000 m deeper. It is possible that rapid resealing of veins, magma-induced hydrofracturing due to buildup of exsolved magmatic fluid, or migration of fluids through a disconnected tube-flow system within the hydrous intrusions generated supralithostatic pressures exceeding the lithostatic load, as is thought to occur in porphyry deposits (Ayuso et al., 2010; Lamy-Chappuis et al., 2020). The 217 to 411 bars at homogenization calculated for LV inclusions hosted in EIR fluorite is equivalent to an uncorrected depth of 0.8–1.6 km at lithostatic pressure and is more consistent with our estimated paleodepth for early-stage mineralization. In the BLAC, such shallow depths for the lithostatic regime are possible because early fluid temperatures approach or exceed the typical brittle-ductile transition temperature of 350–400°C for volcanic rocks (Fournier, 1999; Simpson, 2001), which is likely lower for a carbonatite host rock. Diatreme breccias throughout the complex provide further evidence for episodic pressure buildup and release as exsolved volatiles vented from the system.

The presence of H2O-CO2±SO4 fluids (represented by LV and LVC inclusions hosted in early calcite and EIR fluorite) and Na-Sr-K-REE bicarbonate-sulfate brines (represented by LVS inclusions in LIP fluorite; fig. 7A–E) suggests that fluid immiscibility occurred before the formation of LIP fluorite and its contained LVS assemblage. A possible mechanism for this phase separation is depressurization related to the erupting diatreme. In review of two carbonatites of the Kaiserstuhl complex (Germany)—one genetically linked to an eruptive source (Badberg) and the other a “stalled” carbonatite without evidence of eruption (Orberg)—Walter et al. (2020) suggest that the Badberg carbonatite lost a substantial portion of volatiles during decompression and eruption, whereas the Orberg carbonatite retained fluids, leading to autometasomatism and REE mineralization. Volatiles are known to drive explosive emplacement of diatreme breccias, and it is likely no coincidence that three major diatreme breccia bodies occur near the central carbonatite dike swarm (fig. 1C), with carbonatite that constitutes the diatreme matrix in deeper drill core intervals. Early LV, V, and LVC inclusions represent lower-density phases, at 0.5–0.7 g/cm3 compared with 1.0 g/cm3 for pure water. If these fluids are generated by immiscibility, there would be great volume expansion, generating pressures that exceed the lithostatic regime and sufficient to hydrofracture cap rocks and cause eruption. Though a genetic link between carbonatite emplacement and erupting diatremes in the BLAC remains enigmatic, carbonatite mineralogy and inclusion characteristics suggest that early REE minerals (i.e., burbankite and carbocernaite) crystallized from evolved, high density brines and that devolatilization may have been episodic.

Another potential mechanism for phase separation is decarbonation upon interaction of the carbonatitic melt with alkaline silicate wall rocks, which pushes the bulk composition into the liquid-liquid immiscibility field (Anenburg & Mavrogenes, 2018; Walter et al., 2020). Evidence of decarbonation during carbonatite liquid:wall-rock interaction manifests at the BLAC in the form of biotite- or phlogopite-rich (±K-feldspar) selvages (glimmerite), though these are commonly limited to decimeters beyond carbonatite dike contacts. Vasyukova and Williams-Jones (2023) describe ‘biotitization’ of similar potassium silicate wall-rock lithologies through the reaction:

KAlSi3O8(K-feldspar)+3CaMg(CO3)2(magma)+H2O(in magma)=KMg3(Si3Al)O10(OH)2(phlogopite)+3CaCO3(magma and/or crystals)+3CO2.

The relatively narrow width of biotite selvages suggests that decarbonation reactions and carbonatite melt consumption were limited, allowing much of the volatile load to be retained. This likely promoted autofenitization and the early-stage crystallization of apatite, barite/celestine, and burbankite, confined to the carbonatite intrusions.

Low-temperature LV inclusions in coarse and rhomb-shaped calcite have uncorrected pressures at homogenization between 4 and 8 bars, equivalent to 40 to 90 m paleodepth at hydrostatic pressure. Although these pressures may represent shallow circulation of meteoric fluids, it is more probable that fluids during this stage were trapped at paleodepths similar to those calculated for EIR fluorite-hosted inclusions after the system transitioned to hydrostatic pressure. At a pressure of 150 bars equivalent to 1.5 km paleodepth, corrected temperatures of inclusions hosted in coarse-grained and rhomb-shaped calcite range from 150–181°C and 146–166°C, respectively.

6.3. Spatiotemporal fluid evolution at Bear Lodge

Inclusion populations in the Bull Hill carbonatites and the Smith Ridge area exhibit both broad similarities and important compositional and textural differences. Primary inclusions in Smith Ridge fluorite and smoky quartz are of the LVS variety containing nahcolite and sulfate daughter crystals without halite, much like the secondary and pseudosecondary LVS inclusions in LIP fluorite from Bull Hill. Major distinctions of the Smith Ridge inclusion populations are: 1) the presence of primary rather than (pseudo)secondary LVS inclusions, 2) the absence of burbankite or other REE carbonate phases, 3) lower Th (100–300°C), 4) more crustal 3He/4He (R/Ra), 5) the absence of CO2 in the vapor phase, and 6) greater abundance of (Na,K)Cl in decrepitate mounds.

Although fluids from the two sites are broadly similar, differences in the underlying lithologies, element associations, and inclusion characteristics allow for the possibility that these are distinct events driven by fluids of similar chemistry. Rather than being derived from the central carbonatite dike swarm, the gold-bearing fluorite matrix breccias and smoky quartz veins at the Smith Ridge area are more likely related to volatiles released during emplacement of the pseudoleucite porphyry breccia pipe (fig. 1D). Alternatively, if the fluids responsible for Smith Ridge mineralization originated directly from carbonatite melts, they appear to have cooled, lost some CO2, and precipitated REEs while forming the central Bull Hill and Whitetail Ridge resources. During this process, they may have interacted with groundwater or older granitic wall-rock, acquiring low 3He/4He (R/RA) values. The low R/RA values of Smith Ridge samples likely reflect production of 4He from local uranium-thorium mineralization and/or underlying old crust. Smith Ridge is capped by Archean granite just below the Cambrian sandstone-hosted smoky quartz veins (fig. 1D). Both mineralized Smith Ridge sites also have indications of natural radiation, possibly due to anomalous thorium concentrations: the quartz veins deriving their smoky appearance from thorium radiation and reported fine thorianite inclusions giving the fluorite a dark purple, nearly black appearance. Regardless of the distinct fluid source responsible for shallow-level mineralization, fluid inclusions and their host minerals at Smith Ridge indicate that the mineralizing fluids were enriched in F, CO2, SO4, Ca, Na, and K, but were relatively Cl-poor compared to most intrusion-related magmatic–hydrothermal fluids.

Fluorite samples from the Peterson Claims contain inclusions that record more dilute fluids, likely derived from circulating meteoric groundwater with only a minor magmatic component (fig. 14). These inclusions, composed primarily of F and H2O, differ markedly from the highly saturated, Na-Sr-K-REE bicarbonate-sulfate brine compositions of the central carbonatites. Although full characterization of the inclusions in the distal Peterson Claims samples was not completed, preliminary observations suggest they contain even lower concentrations of SO4, CO2, Na, and K than the fluorite and smoky quartz samples from Smith Ridge, located 1.5 km to the southwest. Alkaline silicate or carbonatite intrusions are thought to be the sources of F, contributing to the formation of fluorspar bedding replacement deposits.

6.4. Implications for alkali+REE transport and mineralization

Bear Lodge LVS inclusions with REE-Sr-alkali-bicarbonate-sulfate compositions are most similar to the Type III or Type IV multi-phase inclusions of Walter et al. (2020, 2021), though the inclusions contain no halite and detection of CO2 was inconsistent. Based on the estimated relative abundances of HCO3-, SO42-, and Cl-, there was insufficient Cl- to saturate the system with respect to halite; however, chloride must be present in the aqueous phase because (Na,K)Cl occasionally formed upon decrepitation of LVS inclusions. Interpreted within the H2O-NaCl system, the absence of halite suggests that LVS inclusions contain <26 wt% NaCl equivalent. However, fluids that contain a substantial CaCl2 component (i.e., 20 wt% CaCl2) experience halite saturation at ~11 wt% NaCl (Vanko et al., 1988), so true salinities of LVS inclusions are likely somewhat lower. Apparent eutectic temperatures from -31.5°C to approximately -21°C in LVS inclusions prohibit precise determination of the fluid system, but suggest that chlorides of Ca, K, and/or Na are present (Goldstein & Reynolds, 1994). Despite these limitations, it does not appear that sufficient Cl- was present to act as an important transport ligand of REEs in this environment.

The experimental work of Anenburg et al. (2020) suggests that evolved, alkali-rich carbonatite fluids are capable of effectively mobilizing REEs in and around carbonatites because of their elevated Na and K content, whereas SO42-, CO32-, F-, or Cl-, acting individually as transport ligands do not satisfactorily explain REE mobility and LREE-HREE fractionation. Carbonatite melts evolve by fractionating calcite, dolomite, and apatite leading to residual enrichment in alkalis, halides, sulfates, and H2O—a fluid composition described as carbothermal or carbohydrothermal and more recently as “brine-melt” (Prokopyev et al., 2016; Yaxley et al., 2022). Alkali-bearing carbonates such as burbankite and carbocernaite are the main REE-bearing minerals crystallizing at this stage. Yaxley et al. (2022) use the term “brine-melt” in cases where “H2O is strongly elevated, and the melts resemble brines.” Bear Lodge LVS inclusions containing nahcolite, burbankite, and alkali sulfates match closely with general descriptions of brine-melts arising from continuous fractionation (i.e., late-stage carbonatite melts that have evolved to brine-like fluids highly enriched in Na+, K+, REE3+, H2O, bicarbonate, sulfate, chloride, and fluoride).

Recent experiments by Yuan et al. (2023, 2024) suggest that “hydrothermal brines” can be generated by continuous fractionation of carbonatite magmas (i.e., brine-melt) or through fluid exsolution depending on whether P-T conditions exceed the supercritical curve of the Na2CO3-H2O system. If the LVS assemblage represents the brine-melt stage, petrographic observations require prior or possibly simultaneous exsolution of a H2O±CO2±SO4 fluid. EIR fluorite and early-stage calcite contain vapor-dominant LV inclusion assemblages that appear to have preceded crystallization of the cross-cutting LIP fluorite containing the LVS assemblage (figs. 3D, 7A). In this respect, the late LVS assemblage—commonly containing >45 vol.% H2O—is difficult to reconcile with the continuous fractionation brine-melt model because substantial volatile loss from Bear Lodge carbonatite dikes and diatremes was likely facilitated by the shallow level of emplacement. Anenburg et al. (2021) state that continuous transition to brine-melt does not preclude the presence of an additional, commonly observed, immiscible aqueous fluid phase, which could explain the two observed inclusion populations (LV and LVS). The experiments of Yuan et al. (2023, 2024) suggest that shallow intrusive carbonatites are likely to produce lower salinity (<20 wt% NaCl equivalent) fluids of simple NaCl-H2O-CO3 composition through fluid-melt immiscibility. Although they would not be considered brine-like, the shallow level of emplacement likely facilitated exsolution of the low salinity, low density fluids trapped in LV inclusions. LVS inclusions that resemble brines are clearly denser and more saline than other fluid types in the system, though not to the extent of brine-melt or “melt-fluid” inclusions reported in some carbonatite inclusion studies, which contain 40–80 vol% daughter minerals and up to 80 wt% NaCl equivalent (e.g., Prokopyev et al., 2016; Xie et al., 2009). By comparison, crystal-packed inclusions observed in fluorite and coarse-grained calcite more closely resemble brine-melts from these other studies (fig. 6A). The crystal-packed inclusions and more common pseudosecondary LVS inclusions in LIP fluorite (fig. 7B–E) may record a progression from brine-melt toward more water-rich compositions.

Alternatively, studies by Guzmics et al. (2019), Berkesi et al. (2020) and Mororó et al. (2024) show evidence of immiscibility between alkali carbonate fluids and carbonatite melts. Through study of melt inclusion behavior in samples from Oldoinyo Lengai volcano in Tanzania, Berkesi et al. (2020) describe a natritess-normative alkali carbonate fluid coexisting immiscibly with both carbonate and silicate melts—similar to the three-phase immiscibility reported by Guzmics et al. (2019) at nearby Kermasi volcano. The authors propose that decompression drives phase separation between the alkali carbonate fluid and a CO2 + H2O-dominated vapor. Following vapor loss, re-equilibration and redistribution of alkalis occurs between the remaining degassed alkali carbonate liquid and melt phases, which includes mixing between a F-rich carbonate melt and alkali carbonate liquid (Berkesi et al., 2020), thus highlighting the importance of CO2 in maintaining immiscibility between the two phases (Mororó et al., 2024). At the BLAC, decompression may have accompanied an explosive diatreme-forming eruption (figs. 1C, 2). After separation of the H2O + CO2 phase represented by vapor-dominant LV inclusions, the re-equilibration process described by Berkesi et al. (2020) or similar back-reaction with calcite might explain the appearance of the LVS assemblage in the latest generation of fluorite.

Regardless of whether LVS inclusions represent evolved or exsolved brine-like alkali bicarbonate fluids, the presence of burbankite and REE detected by LA-ICP-MS in the LVS inclusions genetically links this assemblage to the earliest REE mineralization. Burbankite is commonly reported as an early magmatic REE-bearing mineral in carbonatites, though it is highly ephemeral and commonly altered by late-stage fluids leaving behind hexagonal pseudomorphs partially occupied by a series of Sr, LREE, and Ba replacement minerals (carbocernaite, ancylite, strontianite, Ca-REE fluorcarbonates, and barite) (Andersen et al., 2017, 2019; Anenburg et al., 2021; Broom-Fendley, 2024; Chakhmouradian & Dahlgren, 2021; Moore et al., 2015; Sitnikova et al., 2021; Wall & Mariano, 1996; Zaitsev et al., 1998, 2002). As in other complexes, complete, euhedral burbankite crystals are rare to non-existent at the BLAC and its assignment as a primary phase was based largely on the presence of remnant burbankite in partially replaced pseudomorphs and as inclusions in other early phases (calcite, apatite, and fluorite). Bühn et al. (1999) identified burbankite in carbonatite-derived fluid inclusions hosted in fenitized quartzites and granitic rocks surrounding carbonatites of the Kalkfield Complex, Namibia. Subsequent studies have found burbankite mineral inclusions to be common in carbonates and other minerals in early forming carbonatite facies (Chakhmouradian et al., 2016; Chakhmouradian & Dahlgren, 2021; Platt & Woolley, 1990; Zaitsev et al., 1998; Zaitsev & Chakhmouradian, 2002). In fluorite from the Bull Hill carbonatites, burbankite takes both forms: solid mineral inclusions and crystals in LVS fluid inclusions (figs. 7C–E and 9A, B).

The presence of nahcolite, burbankite, and alkali sulfates in LVS inclusions implies Na-enrichment of the alkali bicarbonate brines—fluids that could conceivably cause sodic fenitization of surrounding wall-rocks. A sodic nature of fenitizing fluids at the BLAC is inconsistent with most of the alteration across the complex, which has been described as dominantly potassic (Felsman, 2009). No major zones of sodic fenitization are known aside from the mention of sodic alteration near Carbon Hill by Felsman (2009). Alternatively, we suggest that the high Na>>K ratios captured in LVS inclusions and potassic-dominant fenitization are a result of preferential Na+ retention to form early crystallizing burbankite. Most Na must have been retained to form the burbankite and the LVS inclusions represent either an evolved carbonatite melt (brine-melt) or synmagmatic fluid of alkali bicarbonate brine composition. This may explain the common co-occurrence of burbankite and fluorite containing the LVS assemblage in carbonatites with more mantle-like δ13C and δ18O values and a paucity of secondary REE minerals. In this scenario, K+ is enriched in a fluid that migrates outward to form more distal expressions of potassic alteration. Sodium is lost from bulk carbonatite compositions as fluids back-react causing replacement of burbankite by the series of other REE±Sr (fluor)carbonates—a process which may have started shortly after formation due to the high solubility of burbankite. The opposite scenario may exert some control on the mineralogy of other, silica-rich carbonatite REE deposits where formation of more sodic fenites or Na-K antiskarn assemblages leave the carbonatite magma depleted in Na and promote crystallization of apatite/monazite or bastnäsite (depending on available phosphorus) rather than burbankite (Anenburg & Mavrogenes, 2018; Yaxley et al., 2022). This scenario supports the conclusion of Anenburg and Mavrogenes (2018) and Anenburg et al. (2021) that hydrothermal fluids do not transport LREEs in carbonatites on a meaningful scale, and thus the ligands most likely to form complexes with REEs are of lesser importance to carbonatite-hosted LREE deposit formation.

Alkali fractionation may also help explain LREE:HREE fractionation at the BLAC. Zones of HREE-enrichment peripheral to the central Bear Lodge carbonatites have been described by Andersen et al. (2016, 2017). Similarly enriched zones around carbonatites at Songwe Hill, Malawi, and Lofdal, Namibia are attributed to preferential transport of HREE by alkali-rich fenitizing fluids (Broom-Fendley et al., 2021). This is further supported by the work of Anenburg et al. (2020) that showed LREE-HREE decoupling to be more extreme in K-bearing experiments indicating higher HREE solubility in the potassic system, consistent with distal potassic alteration and areas of HREE-enrichment at the BLAC. Experiments by Louvel et al. (2022) have shown that in low-T (F-, CO32-)-rich alkaline carbonate fluids, F- does not act as a precipitating ligand, and HREEs may remain in solution. Such F-rich, alkaline carbonate fluids may more plausibly account for the association of fluorite, high field strength elements, HREE, and K-feldspar observed peripheral to the Bear Lodge carbonatites (Andersen et al., 2016).

7. CONCLUSIONS

Results of this study underscore the importance of complex REE+Sr-rich alkali bicarbonate-sulfate brines in the development of carbonatite-hosted REE resources in the BLAC. Comprehensive fluid inclusion analysis reveals a complex system (H2O-Na-K-Sr-REE-SO4-HCO3-F-Cl) that deviates considerably from NaCl/KCl–H2O or NaCl/KCl–H2O–CO2 systems and displays eutectic temperatures consistently below that of NaCl-H2O brines (-21.2°C).

Carbonatite samples reveal three main fluid types: 1) magmatic fluid containing CO2 and SO42-, trapped as liquid-vapor (LV) inclusions with high homogenization temperatures (320–450°C), 2) alkali bicarbonate-sulfate brine or brine-melt represented by liquid-vapor-solid (LVS) inclusions (~270°C to above 556°C), and 3) dilute, low-temperature (117–182°C) magmatic or meteoric water. The solute-rich brines are further characterized by low K:Na ratios and detectable concentrations of Sr and LREEs as evidenced by laser spectra; the presence of nahcolite, strontianite, thénardite, celestine, and burbankite daughter crystals; and decrepitate mound compositions. Although HCO3- and SO42- concentrations greatly exceeded that of Cl- in the examined fluid inclusions, complexation with these ligands may have had only a limited role in the fate and transport of LREEs. Instead, LREEs precipitated within BLAC carbonatite intrusions by one of two processes: 1) evolution of carbonatite melt to the brine-melt stage, facilitated by excess F that acted as a flux, suppressing the calcite liquidus and prolonging melt stability to lower temperatures while simultaneously concentrating Na+, K+, Sr2+, H2O, SO42-, and REE3+; or 2) decompression, possibly during diatreme-forming eruption, that induced immiscibility and phase separation, forming a REE-rich alkali bicarbonate-sulfate brine and a low density CO2+H2O phase. Escape of the CO2+H2O from the system reduced REE solubilities and promoted reaction between the alkali bicarbonate fluid and calcite, leading to precipitation of early REE carbonate minerals such as burbankite and carbocernaite.

Explosive venting of diatremes at Bull Hill, Whitetail Ridge, and Carbon Hill likely caused a net loss of volatiles from the system. However, within the spatially associated carbonatites, a fraction of the volatiles (e.g., H2O and F-) was likely retained, depressing the solidus to some extent. Episodic volatile exsolution followed by re-sealing of the system may explain the co-existence of brine-like LVS inclusions and those containing liquid CO2 that yield anomalously high depth estimates, exceeding the established 1.0–1.5 km emplacement depth for the carbonatite dike swarm.

Peripheral gold resources at the Smith Ridge area are related to fluorite-matrix breccias with distinct fluid characteristics. Primary fluid inclusions in fluorite and smoky quartz veins share similarities with secondary and pseudosecondary inclusions in the carbonatites such as the presence of nahcolite+alkali sulfate daughter crystals and absence of halite (prior to decrepitation). Despite these similarities, the measured crustal 3He/4He values, low REE concentrations, and proximity to a pseudoleucite porphyry intrusion suggest that trapped fluids are related to this separate intrusive event.

Our findings highlight the importance of alkali bicarbonate-sulfate brines in concentrating LREEs through crystallization of Na-Sr-REE carbonates (burbankite) in protore carbonatite at Bear Lodge. Alkali fractionation toward higher K:Na in low-T (<300°C) bicarbonate brines may have facilitated potassium metasomatism and REE transport leading to some of the more HREE-enriched peripheral occurrences. This provides a foundation for tests of a geochemical exploration strategy: Using fenite compositions or alteration assemblages (e.g., K:Na ratios and Na-silicate mineralogy) to help predict whether a carbonatite was likely to crystallize primary Na-rich REE minerals (burbankite) versus other REE minerals (bastnäsite, monazite, apatite).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was fully funded by the USGS Mineral Resources Program. Rare Element Resources Ltd. provided access to drill core and claims in 2010–2013. The manuscript has benefited from helpful discussions with and contributions from Al Hofstra, T. James Reynolds, Matthew Steele-MacInnis, and Heather Lowers. We thank Eric Ellison (University of Colorado) for help with Raman spectroscopy, Andrew Hunt (USGS) for performing bulk extract noble gas isotope analyses, John Wallis (USGS) for map drafting, Corey Meighan (USGS) for data review, and Erin Marsh (USGS) for help with LA-ICP-MS analyses, data review, and guidance. We thank Philip Verplanck, Christopher Gammons, and Michael Anenburg for helpful reviews that improved this manuscript. Claire Bucholz and Page Chamberlain are thanked for editorial handling. Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors contributed to ideas, analysis, interpretation, and writing of selected passages in this manuscript. A.K.A. was responsible for project design, field sample selection, some spectroscopic and decrepitate mound analyses, and writing of the final manuscript with contributions from D.A.O. and M.M.B. Results were compiled and organized for the accompanying data release by D.A.O. Fluid inclusion characterization was principally performed by D.A.O. and M.M.B. including sample preparation, petrography, microthermometry, micro-Raman spectroscopy, and decrepitate mound analyses. M.M.B. provided context from fluid inclusion studies of other ore-forming systems and contributed to LA-ICP-MS analyses.

Supplementary Information

Supplementary material is available in a U.S. Geological Survey data release at https://doi.org/10.5066/P1TTX78H (Olinger et al., 2025).

Editor: C. Page Chamberlain, Associate Editor: Claire E. Bucholz

_regional_map_of_paleogene_igneous_centers_in_the_northern_black_hills_region._b)_genera.png)

_core_samples_of_car.png)

_full_section__transmitted_light_image_of.png)

_fluorite-hosted_salt-melt_inclusion_packed_with_crystals__containing_a_vapor_bubble_at_.png)

_photomicrograph_from_s121-945_of_early__inclusion-rich_(eir)_fluorite_clouded_with_vapo.png)

_backscattered_electron_(bse)_image_of_rod-shaped_burbankite_in_inclusion_pit_from_r11-3.png)

_time-resolved_la-icp-ms_spectra_for_lvs_inclusions_in_calcite_from_sample_bl10-3.png)

_and_ice_melt_(tm_ice_)_temperatures_fo.png)

_regional_map_of_paleogene_igneous_centers_in_the_northern_black_hills_region._b)_genera.png)

_core_samples_of_car.png)

_full_section__transmitted_light_image_of.png)

_fluorite-hosted_salt-melt_inclusion_packed_with_crystals__containing_a_vapor_bubble_at_.png)

_photomicrograph_from_s121-945_of_early__inclusion-rich_(eir)_fluorite_clouded_with_vapo.png)

_backscattered_electron_(bse)_image_of_rod-shaped_burbankite_in_inclusion_pit_from_r11-3.png)

_time-resolved_la-icp-ms_spectra_for_lvs_inclusions_in_calcite_from_sample_bl10-3.png)

_and_ice_melt_(tm_ice_)_temperatures_fo.png)